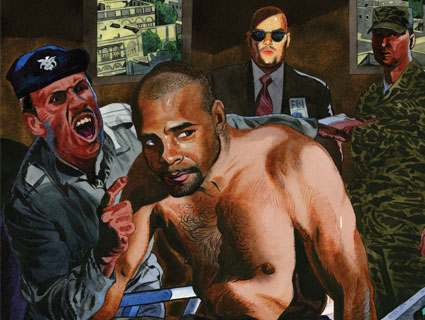

<a href="http://www.flickr.com/photos/46473296@N02/6071555886/">Justin Norman</a>/Flickr

UPDATE: Fikre’s lawyers have written a letter to the Justice Department about his allegations and released a video of him talking about his ordeal.

Last June, while Yonas Fikre was visiting the United Arab Emirates, the Muslim American from Portland, Oregon was suddenly arrested and detained by Emirati security forces. For the next three months, Fikre claims, he was repeatedly interrogated and tortured. Fikre says he was beaten on the soles of his feet, kicked and punched, and held in stress positions while interrogators demanded he “cooperate” and barked questions that were eerily similar to those posed to him not long before by FBI agents and other American officials who had requested a meeting with him.

Fikre had been visiting family in Khartoum, Sudan, when, in April 2010, the officials got in touch with him. He agreed to meet with them, but ultimately balked at cooperating with FBI questioning without a lawyer present and he rebuffed a request to become an informant. Pressing him to cooperate, the agents told him he was on the no-fly list and could not return home unless he aided the bureau, Fikre says. The following week he received an email from one of the US officials; it arrived from a State Department address: “Thanks for meeting with us last week in Sudan. While we hope to get your side of the issues we keep hearing about, the choice is yours to make. The time to help yourself is now.”

Fikre made his way to the UAE the following year, where, he and his lawyer allege, he was detained at the request of the US government. They say his treatment is part of a pattern of “proxy” detentions of US Muslims orchestrated by the the US government. Now, Fikre’s Portland-based lawyer, Thomas Nelson, plans to file suit against the Obama administration for its alleged complicity in Fikre’s torture.

“There was explicit cooperation; we certainly will allege that in the complaint,” says Nelson, a well known terrorism defense attorney. “When Yonas [first] asked whether the FBI was behind his detention, he was beaten for asking the question. Toward the end, the interrogator indicated that indeed the FBI had been involved. Yonas understood this as indicating that the FBI continued to [want] him to work for/with them.” Nelson, the American Civil Liberties Union, and the Council on American Islamic Relations are assembling a high-powered legal team to handle Fikre’s case in the United States.

Fikre’s story echoes those of Naji Hamdan, Amir Meshal, Sharif Mobley, Gulet Mohamed, and Yusuf and Yahya Wehelie. All are American Muslim men who, while traveling abroad, claim they were detained, interrogated, and (in some cases) abused by local security forces; the men claim they were arrested at the behest of federal law enforcement authorities, alleging the US government used this process to circumvent their legal rights as American citizens.

As Mother Jones reported in its September/October 2011 issue, the FBI has acknowledged that it tips off local security forces on the names of Americans traveling overseas that the bureau suspects of involvement in terrorism, and that these individuals are sometimes detained and questioned. The FBI also admits that its agents sometimes “interview or witness an interview” of Americans detained by foreign governments in terrorism cases. And as several FBI officials told me on condition of anonymity, the bureau has for years used its elite cadre of international agents (known as legal attachés, or legats) to coordinate the overseas detention and interrogation by foreign security services of American terrorism suspects. Sometimes, that entails cooperating with local security forces that are accustomed to abusing prisoners. (FBI officials have told Mother Jones that foreign security forces are asked to refrain from abusing American detainees.)

It’s difficult to confirm US involvement in the detentions of Fikre or other alleged proxy detainees—indeed, plausible deniability is part of the appeal of the program. But what’s clear is that Fikre was on the FBI’s radar well before his detention in the UAE. (The FBI declined to comment on his case, as did the State Department.) Fikre, whose only previous brush with the legal system came when he sued a restaurant for having ham in its clam chowder, may have drawn the FBI’s interest because of his association with Portland’s Masjed-as-Saber mosque, where he was a youth basketball coach.

The mosque has been a focus of FBI scrutiny ever since the October 2002 case of the “Portland Seven,” in which seven Muslims from the Portland area were charged with trying to go to Afghanistan to fight with the Taliban in the wake of 9/11. (Six are now in jail; the seventh was killed in Pakistan.) Masjed-as-Saber was in the news again in 2010 when Mohamed Osman Mohamud, a 19-year-old Somali American who sometimes worshipped there, was charged with trying to detonate a fake car bomb provided by an undercover FBI agent.

More recently, three other men who attended Fikre’s mosque—Mustafa Elogbi, Michael Migliore, and Jamal Tarhuni—have found themselves on the no-fly list after traveling abroad. (The government’s use of the no-fly list to prevent American terrorist suspects from returning home after traveling overseas is currently the subject of a major ACLU lawsuit.)

Fikre’s case “really does make a mockery of the FBI’s use of watchlisting as a means of protecting the US,” says Gadeir Abbas, a staff attorney with the Council on American-Islamic Relations. “It’s not a means of protecting America—it’s a tool the FBI uses to put people in vulnerable positions.”

Fikre, who is currently living in Sweden and believes that it would be unsafe for him to return to the United States, has given a series of videotaped interviews detailing his ordeal. His presence in Sweden beyond the three-month window allowed for tourist visas suggests that he has applied for permanent status there, and local media have so far refrained from reporting on the story for fear of affecting his case to stay in the country.

In the interviews, Fikre describes a series of events that are similar to the 2008 case of Naji Hamdan, a Lebanese American auto-parts dealer from Los Angeles who was then living in the UAE. Like Hamdan, Fikre claims he was detained in the UAE, tortured (including with stress positions and beatings on the soles of his feet, so as to not show marks), and asked about his activities in the United States. Like Hamdan, Fikre believed a western interrogator was present in the room at some points during his detention, because when he could peek out under his blindfold (“after being kicked/punched and falling over,” Nelson says) he occasionally saw western slacks and shoes. “In those occasions there was a fair amount of whispering,” Nelson added.

The similarities between the two cases were so striking that Michael Kaufman and Laboni Hoq, lawyers who are representing Hamdan in his separate case against the government, initially thought that Fikre had simply parroted Hamdan’s story. But once they heard more, they decided “the backstory of why the government was interested in him was reasonable and something that didn’t sound fabricated,” Kaufman said. “It seemed like a long way to go for a lie,” Hoq added.

A key difference between Hamdan’s and Fikre’s stories is that Hamdan eventually confessed—under torture, he now emphasizes—to being a member of several terrorist groups, including Al Qaeda. He ultimately spent 11 months in UAE custody before being deported to Lebanon, where he now runs a children’s clothing store. Despite an extensive FBI investigation, he was never charged in the United States.

Fikre, his lawyer says, “never confessed to anything”—”thankfully.”

“The FBI does this stuff because they can get away with it,” Nelson says. “But the bureau has totally destroyed any relationship it had with the Muslim community in Portland.”

UPDATE, Wednesday, 1:00 p.m. EST: Fikre’s lawyers have released a video of him talking about his ordeal (they’ve also written a letter to the Justice Department). You can watch the video here: