Saturday’s arraignment of the alleged 9/11 conspirators at Guantanamo’s war court wheezed along like an old man with a two-pack-a-day habit, with the accused boycotting the proceedings and their defense attorneys seeking to shift the focus of the proceeding to their clients’ abuse in American custody.

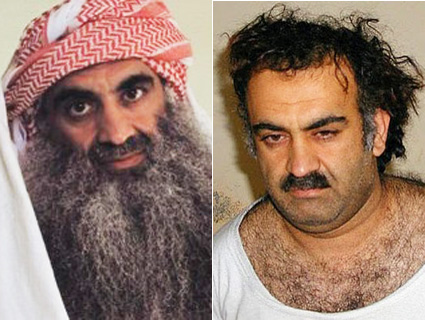

“He is not participating because of the torture that was imposed upon him,” said David Nevin, the attorney representing Khalid Sheikh Mohammed. Nevin said that Mohammed, who appeared in white attire with his beard dyed reddish-brown, was “deeply concerned about the fairness of the proceeding.”

All five detainees opted to silently protest the arraignment, where it took about an hour and a half merely to establish legal representation for the defendants as Judge Captain James L. Pohl struggled to control the courtroom at times. The hearing was a stark contrast from four years earlier, when Mohammed had gone on an six-minute rant claiming responsibility for everything from the 9/11 attacks to the gruesome murder of Wall Street Journal reporter Daniel Pearl. Where Mohammed had once sought to be tried by military commission, comparing himself to George Washington battling the British, Saturday he showed no evidence of his previous taste for theatrics and bombast. The Obama administration had initially intended to try Mohammed and his alleged co-conspirators in a federal court in New York but reversed course after a fierce bipartisan backlash. While opponents of a criminal trial argued that it would be both a security risk and a spectacle, the scene at Gitmo’s war court could only be described as a mess.

“I think a federal judge would have said, ‘Sit down, counsel!’ about 90 minutes ago,” said Andrea Prasow, senior counterterrorism counsel with Human Rights Watch, who was observing the arraignment from Fort Meade, Maryland. On the other hand, Prasow said, Pohl may be concerned about how bringing the hammer down on the defense might impact the legitimacy of the proceedings, since military commissions are more favorably disposed toward the prosecution than federal courts. “Pohl is obviously aware that the world is watching,” Prasow said.

Mohammed and the other detainees removed or failed to use their earphones, forcing Judge Pohl to bring in translators to simultaneously relay the proceedings in Arabic to the stoic defendants. The video feed for the war court, which is delayed in order to prevent accidental disclosure of classified information, cut out for a few moments. When it returned, Nevin accused the court of cutting the feed to block any reference to Mohammed’s alleged torture. At one point, Ramzi bin al-Shibh halted the proceedings by rising to pray. Two of the detainees, Ammar al-Baluchi and Mustafa Ahmed Adam al-Hawsawi, passed around a copy of The Economist. Cheryl Bormann, an attorney for Walid Muhammad Salih Mubarak Bin’ Attash, appeared in a black cloak and head scarf, advising the judge that other women in the courtroom should dress more conservatively because the defendants were worried about “committing a sin under their faith.” Bin’ Attash had been restrained to his chair because he had reportedly refused to come willingly to the court—painfully, his attorney said. Nevertheless, he refused to speak directly to Judge Pohl to assure him he would “behave” if the restraints were removed. Following a lengthy exchange, Bin’ Attash promised his attorney he would not disturb the proceedings, and Judge Pohl directed the guards to undo his restraints.

Around 90 minutes into the proceedings, Pohl finally managed to ask each detainee whether he accepted the legal representation assigned to him. The detainees refused to respond—some staring at their laps, others flipping through The Economist—as Pohl repeated over and over, “The accused refuses to answer.”

Ramzi bin al-Shibh was the only defendant to speak directly to Judge Pohl during the proceeding. “Maybe they are going to kill us at the camp and say we have committed suicide,” the detainee said.

About two hours into the proceedings, Judge Pohl finally expressed frustration at the pace of the arraignment. “Why is this so hard?” he asked. And we haven’t even gotten to the trial yet.