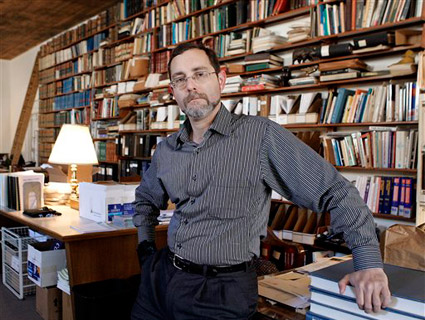

Courtesy Alex Friedmann

Tomorrow, at the annual meeting of Corrections Corporation of America, the nation’s largest private prison company, shareholder activist Alex Friedmann will have exactly two minutes to speak about the unconventional resolution he introduced earlier this year to the chagrin of CCA’s board.

The resolution is unconventional because it concerns not corporate profits or dividends, but the well-being of the roughly 81,000 inmates in CCA’s care. Friedmann, too, is unconventional, for although he holds just $2,000 or so worth of CCA stock, he has inside knowledge of the company’s practices—because he served time at one of its prisons.

Indeed, Friedmann spent six years at CCA’s South Central Correctional Facility in Clifton, Tennessee—part of his 10-year sentence for attempted murder, armed robbery, and attempted aggravated robbery. Since getting out in 1999, he has been an advocate for prisoners’ rights and criminal-justice reform. Now he’s an editor with Prison Legal News and head of Private Corrections Institute, a nonprofit watchdog.

Friedmann’s controversial resolution addresses the long-standing problem of rape in US prisons and jails. If it passes, CCA’s board will have to submit twice-a-year reports to stockholders detailing the board’s oversight of company efforts to curb rape and sexual abuse, and include detailed statistics on any such incidents. “If CCA has to report this information they will have a greater incentive to reduce rape and sexual abuse because it will make the company look bad if they have very high numbers,” he says. “And if they have to report this, the public, i.e., CCA shareholders, will be able to judge the effectiveness.”

Although Friedman was neither a victim of rape nor a personal witness to it during his CCA stint, he believes that private prisons are among those least attentive to the sexual victimization of inmates by guards and other inmates. For instance, in a 2007 survey of local jails by the Bureau of Justice Statistics, a CCA facility in Torrance County, New Mexico, clocked in with the highest rate of sexual victimization (13.4 percent), more than four times the national average. It also had the highest rate of staff-on-inmate sexual victimization—7 percent, as compared with a national average of around 2 percent.

CCA can certainly afford to address the issue. The longtime industry leader in prisons and immigrant detention, it owns or operates 67 facilities (see table of its customers below) and boasts about $1.7 billion in annual revenues—more than 40 percent of which come from the federal government and most of the rest from the states and localities. The company reportedly employs 35 lobbyists on Capitol Hill, with hundreds more working in 33 states over the past eight years. Chart: Michael Mechanic

Chart: Michael Mechanic

While many people view prison rape with “shoulder-shrugging acceptance,” Friedmann is hardly alone in declaring it a national disgrace. His bid has gained the support of advocacy groups including the National Organization for Women, the National Lawyers Guild, and the Justice Policy Institute. Back in 2003, moreover, Congress passed the Prison Rape Elimination Act by a unanimous vote, and President George W. Bush signed it. The law mandated the first comprehensive collection of data on prison rape—and the results were eye-opening: In 2008 alone, there were an estimated 216,000 sexual assaults on men, women, and children in American detention facilities—that’s 600 a day, notes the group Just Detention International, or 25 an hour.

The federal law also required detention facilities to adopt a “zero tolerance policy” toward rape and sexual assault. CCA-run institutions have fallen short, argues Friedmann, whose supporting materials contain additional examples of poor oversight and detail four lawsuits alleging that its employees abused inmates. (Last December, for instance, the ACLU filed a suit alleging that a guard at the company’s Eloy Detention Center in Arizona had masturbated into a cup and then demanded that a transgender prisoner drink the result.) But Friedmann’s resolution hinges on language investors can relate to: “A failure by the Company to adequately address this issue, and the negative publicity, loss of business and litigation that results, constitutes a risk to the Company and a threat to shareholder value.”

CCA was none too happy with Friedmann’s resolution. He filed it, as required, with the Securities and Exchange Commission, which must verify that corporate resolutions are relevant before the documents are attached to proxy materials and sent to shareholders for a vote.

CCA’s board—which includes former Clinton/Gore official Thurgood Marshall Jr. and Dennis Deconcini, the former GOP senator from Arizona—responded with a letter to the SEC , urging commissioners to kill the resolution. The letter argues that the company already intends to start posting such reports on its website annually and further implies that Friedmann is a disgruntled ex-con with a bone to pick. The SEC (surprisingly, given its reputation) sided with Friedmann—whereupon CCA amended the proxy package with a lengthy rebuttal to his resolution, asking shareholders to vote it down.

But Friedmann could win this one yet. Institutional investors—which, along with banks, control the majority of CCA stock—often hire proxy firms to analyze shareholder resolutions and vote on their clients’ behalf. In this case, Friedmann says two of the three proxy companies involved told him they planned to vote his way. The result will be announced at tomorrow’s meeting in Nashville, where, no matter what the outcome, Friedmann will have his two minutes at the podium.