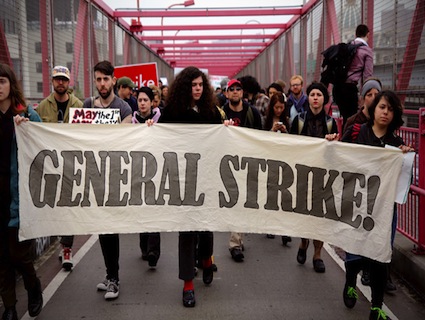

Protesters march in the all-purpose Solidarity Rally near Union Square in New York on Tuesday. See more photos from the march.Photo: <a href="http://motherjones.com/authors/jacob-blickenstaff">Jacob Blickenstaff<a/>

On Tuesday afternoon, in a departure from recent history, Occupy Wall Street took the form of a duly-permitted march.

To mark May Day, over 15,000 people filled New York City’s Union Square for an all-purpose solidarity rally. Tom Morello and Das Racist performed, reporters scouted out eccentric-looking interviewees, and friends shared rumors about what the night might bring. At 5:30 p.m., the Union Square crowd emptied out onto Broadway, heading south toward the Financial District. Since the marchers had a permit, the NYPD officers blanketing the route didn’t interfere.

(Mother Jones journalists took photos at May Day marches in New York and Oakland, and Josh Harkinson wrote about what Occupy should do next.)

The marchers’ presumptive destination was either Wall Street or Zuccotti Park, though as usual with the Occupy movement, no one seemed quite sure. After more than two hours of slow-paced marching, the procession had reached an ill-defined endpoint in Lower Manhattan. Wall Street itself appeared impenetrable—the entrance was fortified with multiple layers of metal barricades manned by cops. Zuccotti Park was inaccessible, too—the plaza was brimming with police, including Deputy Inspector Johnny Cardona, who memorably sucker-punched a demonstrator in the face last October without provocation. (On April 28, Cardona yanked Katherine Bromberg, a New York Civil Liberties Union legal observer, off the sidewalk and arrested her; charges of disorderly conduct and blocking pedestrian traffic were later dropped.)

The occupiers’ public schedule contained only a coy hint of what might transpire later—there’d be an “Afterparty,” it read, at 8 p.m. For a while, though, people just lingered; May Day seemed in jeopardy of dissipating prematurely. Then, at around 8:30, a man associated with OWS Direct Action called out a sudden mic check, directing everyone within earshot to follow him immediately. He hung an abrupt left onto Bridge Street, due east, and then darted south across Water Street—in the direction, it turned out, of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Plaza.

“Welcome to the People’s Assembly!” shouted the OWS tactician, now perched at the plaza’s entrance. He waved a yellow Occupy-themed flag to attract attention. “Come enjoy yourself.”

Within 15 or 20 minutes, hundreds of people had funneled into Vietnam Veterans Memorial Plaza, which is situated at the base of 55 Water Street, America’s second largest privately owned office building. The skyscraper’s tenants include Standard & Poor’s corporate headquarters and a branch of J.P. Morgan Chase, two facts which, when pointed out by an activist via the people’s mic, prompted sustained boos.

Like Zuccotti Park, Vietnam Veterans Memorial Plaza is zoned as a “privately owned public space,” but unlike Zuccotti, it has a posted curfew of 10 p.m. Inside, a large amphitheater proved ideal for the People’s Assembly—an outsized, expedited version of the General Assembly that had been the lifeblood of Occupy in its early stages. Marisa Holmes, one of the Occupy movement’s original architects, facilitated the conversation with poise.

Just when the plaza appeared full to capacity, another large band of marchers could be heard approaching in the distance, led, as always, by a tireless team of drummers. To accommodate the growing crowds, facilitators instituted a mic check with four distinct echoes. Newfound optimism swirled, but with less than an hour till the posted curfew, the specter of a police incursion loomed. That looming threat—combined with a new location, scores of new faces, and a new season ahead—generated fevered anticipation, reminiscent of Occupy’s zenith last fall.

A slate of emotive speakers, beginning with Jumaane Williams, a New York City councilman, reinforced this sense.

“Greetings from Brooklyn,” Williams declared on the people’s mic, acknowledging the presence of his colleague Ydanis Rodriguez. Both men are ardent critics of the NYPD, and both have been arrested during Occupy events. “History is begging you,” Williams exhorted—his sentences repeated a full four times over by the crowd, so everyone could hear. “History is pleading you. Continue to agitate. Continue to agitate. Continue to agitate,” he crescendoed, to roars. “Until they hear you!”

Next to speak was John Hector, who last fall acted as sort of emissary between Occupy Wall Street and a coalition of outside activists targeting the NYPD’s “stop-and-frisk” policy—a method of aggressive, racially disparate policing favored by Mayor Michael Bloomberg and NYPD Commissioner Ray Kelly.

“Once upon a time,” Hector began, over the people’s mic, “Occupy Wall Street was a vehicle to get black and brown voices heard. And I told my story—about my own personal experience of police terror and ‘stop-and-frisk.’ I want to say that I thank Occupy Wall Street very much. Because if it was not for this movement, I probably would not be taking a stand right now.”

As the People’s Assembly wore on, speakers were occasionally interrupted by sporadic calls of “mic check,” as interrupters relayed word of authorities’ latest moves. Members of Veterans for Peace and Occupy Faith NYC, a coalition of religious figures in fellowship with OWS, volunteered to “stand on the front lines” and defend against any police intervention. By then it was past 9:30 p.m., and hundreds of officers had amassed in every direction. “What I want to say to all of you here, is very simple,” proclaimed the Rev. Michael Ellick of Judson Memorial Church, a longtime champion of Occupy. “Welcome home!”

Could a contingent of Vietnam veterans and clergy deter police from dispersing this new assembly—located, after all, at Vietnam Veterans Memorial Plaza—even if only to allow a bit more time for collective strategizing? In the amphitheater, there was preliminary talk of encircling a fountain by “soft-locking” arms. Some pledged to stay overnight, no matter the consequence. A drum circle materialized, and the familiar energy of perpetual percussion washed over the plaza.

At 9:45—fifteen minutes before it was due to close—a stream of 50 officers entered the plaza from FDR Drive. Led by Donald McHugh, the NYPD’s notorious deputy inspector for counterterrorism, they were told to walk in a single file. “And don’t talk,” McHugh instructed.

“What’s going on tonight?” McHugh snarled at me. “You just get out of work?”

By 10:00 p.m., the occupiers had clearly not hatched any kind coordinated plan to hold the space. Reaching meaningful consensus would require more time. Shortly after the deadline, bullhorn-wielding officers with the Manhattan South Task Force penetrated the plaza and trumpeted orders to vacate; rows of police with batons cleared out the stragglers, overeager observers, and journalists. A battalion of NYPD “white shirts” descended on the clergy and Vietnam Veterans, who, as promised, had stayed behind with arms locked.

And so, any hopes for an extended reoccupation were dashed. With no other options at their disposal, bands of disconnected demonstrators flowed into the narrow side streets of the Financial District, spurring a round wayward splinter marches. In what is by now a familiar pattern, officers employed every available method to stifle these (unpermitted) marches, indiscriminately closing off sidewalks—sometimes whole blocks—and suddenly enforcing obscure ordinances as pretext for arrests.

By 11:30, the marchers and journalists who remained on the scene retired to Zuccotti Park for some “passive recreation“—the maximum level of exertion permitted by park rules. Jeff Smith, a fixture of the original OWS media team, was there unwinding. He wondered aloud if the day’s ultimate legacy could be to reinstate May 1 as an annual occasion for serious activism across New York City.

Smith’s theory sounded plausible enough. But May Day 2012 had drawn to a strange close, and after hours of rancor, there was just stillness.

“Lower Manhattan is overflowing with police,” Nick Pinto of the Village Voice tweeted. “Every corner, every street, dozens of officers. Otherwise, the streets are dead.”