"Extreme Hot Days" to Rise for LA Courtesy of <a href=http://newsroom.ucla.edu/portal/ucla/climate-change-in-la-235493.aspx">UCLA</a>

A team of UCLA scientists recently fed about 20 global climate models into powerful supercomputers to calculate just how much Los Angeles-area temperatures might increase over the next few decades. After months of complex computing—about eight times as many individual calculations as there are grains of sand on the West Coast of the United States—the scientists’ computers spit out some troubling projections.

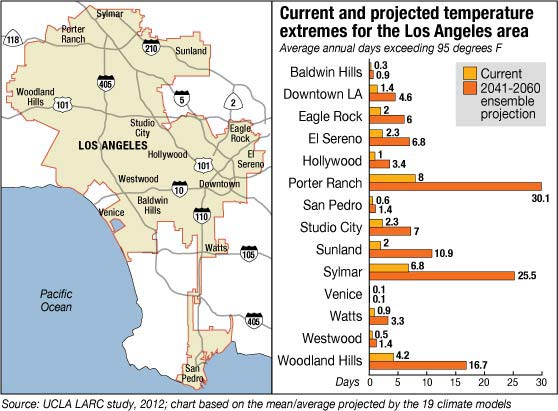

By 2041, the UCLA team found, temperatures in Los Angeles will rise by an average of 4 to 5 degrees Fahrenheit. The number of “extreme hot days”—days with temperatures above 95 degrees—will triple in the downtown area and will quadruple or more in inland valleys, deserts, and mountains.

Dramatic shifts will occur even if the world manages to successfully curtail greenhouse gas emissions. In the unlikely event that the world starts to get its emissions problems under control, Los Angeles temperatures will still reach 70 percent of the study’s “business-as-usual” levels, the researchers found.

Alex Hall, the head researcher on the study, previously focused his work on global temperature changes. (He’s a lead author on the United Nations’ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change reports.) He was surprised to discover just how much temperature change many Los Angelenos could see during their lifetimes. “It was very eye-opening,” he says.

The Department of Energy and the Los Angeles Regional Collaborative for Climate Action and Sustainability (LARC)—a consortium of Los Angeles-area governments, organizations, and universities, including UCLA, that collaborate on climate change and sustainability solutions—funded the study. LARC hopes to use the data to coordinate policy efforts and adaptation strategies.

The UCLA study’s findings could eventually drive decisions such as where to locate cooling centers for vulnerable populations and how to plan water conservation. The data could also inform the design of other sustainability initiatives, including reducing energy use associated with air conditioning, expanding cool roofs, and planting greenery. But the city still has “a long way to go” in developing a working solution to the impending midcentury heat, Paul Bunje, LARC’s managing director, told Mother Jones. “We don’t have a choice in adapting to climate change. It’s coming here, in my backyard. It’s not just the polar bears.”

The “most important thing,” about the UCLA study, Bunje says, “is we now have fine-scaled data to do some real planning in the city.” Now it’s up to LARC and the city to make sure that data gets used.