Whitewater-Baldy Complex Fire, New Mexico: Kari Greer | USFS Gila National Forest

Whitewater-Baldy Complex Fire, New Mexico: Kari Greer | USFS Gila National Forest

Wildfire season is well underway. Based on the number of acres burned in 2012 to date, this year is running below the 10-year average (1,012,419 acres compared to 1,546,333 acres). What’s notable though is that although there have been fewer fires (24,062 this year-to-date versus 33,755 for the 10-year average), a few are giant beasts:

- Honey Prairie Complex Fire in the Okefenokee Swamp, Georgia, began burning in 2011 and was only officially declared extinguished a year later in April 2012 after burning 309,200 acres (483 square miles)

- Whitewater-Baldy Complex Fire (more below), largest in New Mexico history, currently burning 280,075 acres

- High Park Fire in Colorado (great MoJo piece by Tim McDonnell and James West here) now burning 46,600 acres

- Little Bear fire in New Mexico currently burning 37,520 acres

- Easter Complex in Virginia (now inactive) burned 35,821 acres

- County Line Fire in Florida now burning 34,936 acres

- Duck Lake Fire in Michigan now burning 21,069 acres

- Sunflower in Arizona now burning 17,618 acres

- Gladiator in Arizona now burning 16,240 acres

All numbers courtesy of the National Interagency Fire Center’s (NIFC) latest incident management report. You can see the full list, updated frequently, here.

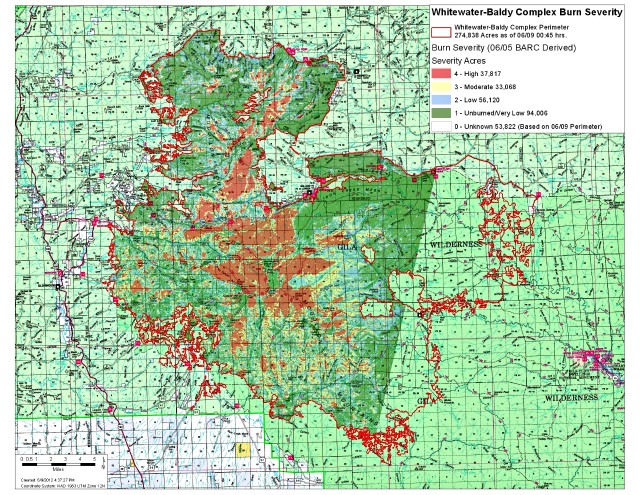

Whitewater-Baldy Complex burn severity map as of 9 June 2012 (click for larger version): Brian Park / USFS

Whitewater-Baldy Complex burn severity map as of 9 June 2012 (click for larger version): Brian Park / USFS

The enormous and aggressive Whitewater-Baldy Complex Fire in the Gila National Forest began as two fires—the Baldy Fire ignited 9 May and the Whitewater Fire detected 16 May—both ignited by lightning. They merged on 24 May and are now burning in terrain the US Forest Service lists as extreme: so remote, steep, and rugged as to severely hamper firefighting efforts.

The good news on this fire is that a different kind of management may lessen its impacts compared to a similar megafire last year, the Las Conchas, also in New Mexico. That 2011 conflagration burned so hot in such dense vegetation that all life burned to the ground. Later, seasonal thunderstorms flooded the denuded slopes and clogged waterways with silt and ash. But things may be better for the Gila. Since the 1970s, Gila National Forest managers have let wildfires burn during favorable conditions in order to knock back the vegetation that fuels fire. Consequently, the Whitewater-Baldy Fire has burned with low-to-moderate intensity. Hopefully much will survive it.

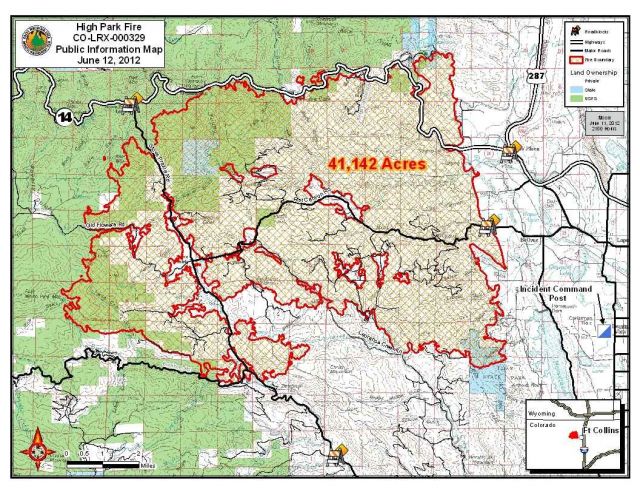

High Park Fire, Colorado, burn map as of 12 June 2012 (click for larger version): USFS

High Park Fire, Colorado, burn map as of 12 June 2012 (click for larger version): USFS

As for the rapidly growing High Park Fire, now the third largest in Colorado history, Jeff Masters at Wunderblog points out how it’s abetted by a warming climate that fuels the spread of pine-killing beetles:

According to the Denver Post, the High Park Fire is burning in an area where 70% of the trees that have been killed by mountain pine beetles; the insects have devastated forests in western North America in recent years. As our climate change blogger, Dr. Ricky Rood explains, the pine beetle is killed (controlled) by temperatures less than -40°F. This is at the edge of the coldest temperatures normally seen in the U.S., and these cold extremes have largely disappeared since 1990. In Colorado, the lack of -40°F temperatures in winter has allowed the beetles to produce two broods of young per year, instead of one. The beetles are also attacking the pine trees up to a month earlier than the historic norm.

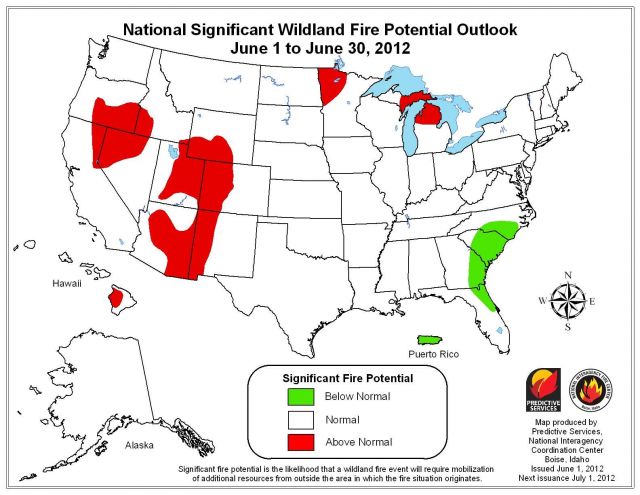

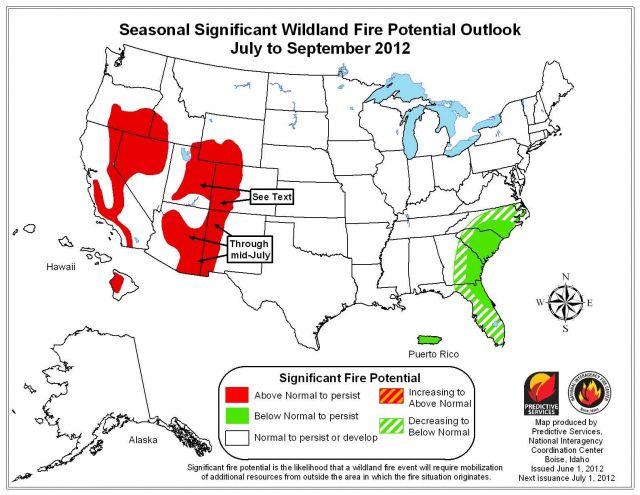

National Interagency Fire Center

National Interagency Fire Center

The maps above show the potential for significant fire for the month of June (top) and for the July-to-September season (bottom). “Potential” is defined as the likelihood that a wildland fire event will require mobilization of firefighting resources from outside the area where the fire originates. As you can see, things may get worse in the West, but better in the Upper Midwest. The full NIFC report is here.