<a href="http://www.shutterstock.com/pic.mhtml?id=94862134">Eva Vargyasi</a>/Shutterstock

Americans just got yet another reason to brush and floss regularly.

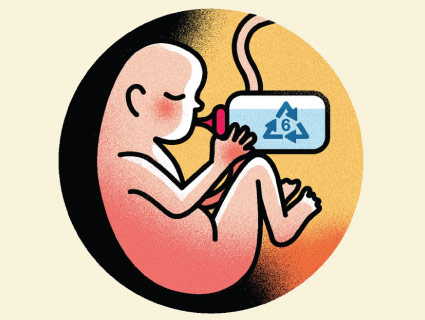

It turns out that those tooth-colored materials dentists now use to fill most cavities are made with derivatives of bisphenol A, the controversial endocrine-disrupting chemical used in a wide range of plastic products, including polycarbonate water bottles and food-can linings. Over the past decade, the BPA derivative known as Bis-GMA has been the predominant dental filler, going into the mouths of some 100 million Americans a year, according to one expert. And now a study in the journal Pediatrics is linking Bis-GMA fillings to worse behavioral outcomes in children.

This isn’t the first time dental fillings have come under scrutiny. These off-white plastic composites are the supposedly safe alternatives to silvery mercury amalgam fillings, which have raised a number of neurotoxicity concerns. The FDA considers mercury amalgams safe, although countries like Norway and Denmark have banned the use of mercury in fillings (PDF). For largely aethestic reasons, the composite fillings have exploded in popularity and now outnumber amalgam fillings 10 to 1.

The researchers actually set out to investigate the potentially adverse effects of the amalgams. To their surprise, it was the Bis-GMA composite fillings that were associated with worse scores on behavioral assessments in categories such as maladjustment and anxiety.

The five-year study surveyed the parents of 534 children, ages 6 through 10, who were randomly assigned either amalgam or composite fillings. The results were dose-dependent: Kids with a greater number of composite fillings scored worse than those with fewer—an effect not seen with amalgam fillings. This, along with the random assignment of filling types, helped the scientists rule out statistical confounders, bolstering the possibility of a causative link between the Bis-GMA and the lower behavioral scores.

The effect was subtle, however—just a few percentage points. “The average behavioral differences were very small, and they probably wouldn’t be noticeable in most children,” explains lead author Nancy Maserejian, a senior scientist at the New England Research Institutes. But Bis-GMA could present problems for children who are considered at risk for behavioral problems.

The mechanism by which Bis-GMA might affect behavior is unknown. As an endocrine disruptor, BPA has been linked to anxiety and depression, though it is unclear whether fillings made from Bis-GMA—which consists of a BPA molecule chemically bonded to a molecule called glycidyl methacrylate—actually release BPA over time. Another study, involving only 19 children, found elevated BPA levels in kids’ urine after they received Bis-GMA fillings—possibly the result them ingesting trace amounts of residual BPA during the procedure. The American Dental Association contends that this one-time exposure is two to five times lower than the estimated daily exposure from food and other sources.

Bis-GMA fillings do degrade over time—most last fewer than eight years. Studies during the 1990s showed that Bis-GMA may release endocrine disruptors, but those studies used fillings that since have been phased out, according to Jeffrey Stansbury, a professor of restorative dentistry at the University of Colorado-Boulder.

The existing alternatives to mercury amalgam and Bis-GMA composite fillings are seldom used. One of them is urethane dimethacrylate, which isn’t associated with any behavioral effects, but it looks less natural in the mouth and doesn’t last as long as the other types. It’s a tricky balance: Dental fillers must be pliable enough to pack into a cavity and get hard enough to withstand daily chewing—yet not too hard so as to wear down the enamel on neighboring teeth.

Stansbury says 3M makes a product called Filtek that could work as an alternative. But it requires a different technique to apply, and inertia in the dental community has kept it from gaining popularity. So unless the FDA bans Bis-GMA in dental fillings—not likely, since it recently refused to ban BPA in can linings—or patients start demanding better options, it’s likely to remain that way.

Clearly the worst option, however, is leaving cavities untreated, which can result in painful and even life-threatening infections, sepsis, or pneumonia. Basically, by the time you get a cavity, it’s too late to avoid putting chemicals in your mouth. “The take-home message for parents and people,” Maserejian says, “is just to prevent cavities in the first place.”