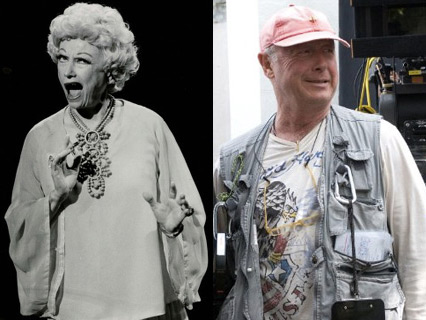

<a href="http://digital.lib.uh.edu/cdm4/item_viewer.php?CISOROOT=/p15195coll38&CISOPTR=129&CISOBOX=1&REC=3">KUHT</a>/Unviersity of Houston Libraries ; <a href="http://www.imdb.com/media/rm3636759552/nm0001716">Ron Phillips</a>/Touchstone Pictures

On Monday morning, Phyllis Diller was found dead at her Los Angeles home, having passed away “peacefully in her sleep” at the age of 95. Diller, a roaringly funny, trailblazing comedienne, has an extensive résumé in need of no qualification.

Even into her elderly, feeble years, she stayed fierce, endearing, and thoroughly watchable. My introduction to her work came rather late—when I was 17 and had just rented the documentary The Aristocrats in early 2006. She, like the other comedians interviewed for the movie, riffs on the classic improvisational “Aristocrats” joke. On the DVD’s special features, there is a deleted scene in which Diller takes a break to tell a Monica Lewinsky joke. In that short bit, she is effervescent, quietly captivating, and, most shockingly, she manages to keep the joke (a Lewinsky joke) from sounding unpardonably dated.

Therein lies what made me such a fan in the first place: It wasn’t her big, outlandish moments (as great as they frequently were) that really made her shine—it was the fact that she could floor you with the small moments and the little things, and make it look like a cakewalk all the while.

The following is by the late author Christopher Hitchens (to whom we bid farewell late last year) from back in December 2008, in which he writes about a Christmas card he received from Diller. I mean this in only the best of senses: The anecdote tells you everything you need to know about the woman:

I had never before been a special fan of that great comedian Phyllis Diller, but she utterly won my heart this week by sending me an envelope that, when opened, contained a torn-off square of brown-bag paper of the kind suitable for latrine duty in an ill-run correctional facility. Duly unfurled, it carried a handwritten salutation reading as follows:

Money’s scarce

Times are hard

Here’s your fucking

Xmas card

And less than 24 hours prior to Diller’s death, the entertainment industry lost another one of its stars, this time to suicide. Director Tony Scott, 68, jumped from the Vincent Thomas Bridge into the Los Angeles Harbor. His body was recovered in the mid-afternoon on Sunday, with suicide notes found in his office and his car.

At the time of his death, Scott had several major projects in the works, including a film adaptation of Bill O’Reilly’s (error-ridden) nonfiction book Killing Lincoln, set to air on the National Geographic Channel.

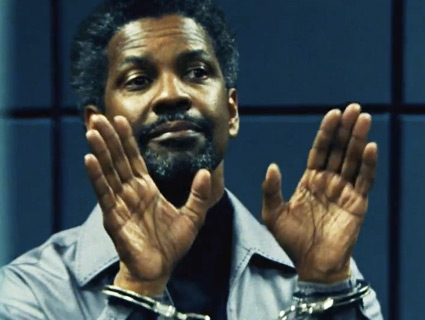

Throughout his three decades in Hollywood, it was almost too tempting to take shameless, critical swipes at Scott (only six months ago, I made a mild one in this review for Mother Jones, just for the hell of it). He was the younger, significantly less esteemed brother of Ridley. His frenetic and melodramatic style recurrently got the best of him. He had a clammy grasp on human drama. His penchant for visual excess made the eyes ache more often than they made the heart flutter. And his obsession with putting Denzel Washington and imperiled trains in the same movies seemingly all the time was…confounding, to say the least.

But in spite of all this, Scott’s better work had that unmistakable touch of a maverick, from crowd-pleasers like Top Gun (1986) and Days of Thunder (1990), to blood-and-guts-mottled fare like Man on Fire (2004) and Domino (2005). He was equal parts pure formula and wild deviation, earnestness and cheap laughs, garish colors and overcaffeinated camera work, loud music and hushed dialogue.

When Scott wasn’t overpowered by his own distinct style, he demonstrated he had something that was all too rare among those working in the big business of violent pop art: He took risks, audience turn-offs be damned.

And that’s something to acknowledge, and someone to sorely miss.

Take a few minutes to revisit Beat The Devil (2002), the short film/commercial Scott directed for the BMW-sponsored series The Hire. Beat The Devil stars Gary Oldman as a Keith Richards-style Devil, Clive Owen as the driver, and Marilyn Manson and James Brown as themselves. Basically, James Brown bets Satan that he and Clive Owen can out-drag-race him through the streets of Las Vegas. If Satan wins, he gets both their souls. If they win, the Godfather of Soul gets an extra 50 years of fame and fortune.

There’s a lot of funk music, and Gary Oldman/The Devil wields a rusty shotgun. It might actually be the Tony Scott-iest thing that Tony Scott ever did:

And now, here’s (an alternate version of) the single greatest scene Scott ever directed: The Mexican standoff at the end of the Quentin Tarantino-scripted True Romance (1993). [Spoilers—you know, it being the climax of the movie, and all.]