Shauna Prewitt says her rapist tried to seek custody of the child conceived during the assault. <a href="http://www.shaunaprewitt.com/">Shauna Prewitt</a>

The debate over Rep. Todd Akin’s widely condemned comments on “legitimate rape” has largely centered on abortion and Republican efforts to outlaw the procedure, even in cases of rape. But the controversy has also uncovered a little-discussed issue: When some rape victims do choose to give birth to a child conceived through sexual assault, they find that the legal door is left wide open for their victimization to continue. It sounds unfathomable, but in many states the law makes it possible for rapists to assert their parental rights and use custody proceedings as a weapon against their victims.

Shauna Prewitt says it happened to her, in Akin’s home state of Missouri. In 2004, Prewitt was in the midst of her senior year in college when she was allegedly raped. Nine months later, she gave birth to a baby girl, who today is seven and a half. Shortly after her daughter’s birth, when Prewitt was pursuing charges against her accused rapist, he suddenly served her with papers requesting custody of their daughter. At first, Prewitt thought it was so ridiculous she laughed it off. Then, the truth sank in:

“I was struck with terror, not only with the idea of letting my child be around him, but also having to spend the next 18 years of my life tied to him,” she says.

Prewitt, who now works as an attorney in Chicago, thought there was no court on earth that would allow her alleged rapist (he was never convicted) to have custody rights. But her lawyer informed Prewitt that, due to Missouri law, her case wasn’t a slam dunk. The state wouldn’t allow her to fight the custody request directly—the court would have to file a petition independently.

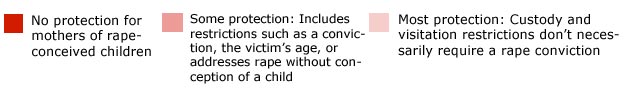

At least Missouri has a law on the books allowing the court to step in and terminate parental rights in a case like Prewitt’s—at least 27 states have no statutes to protect the mothers of rape-conceived children. Meanwhile, victims continue to come forward with horror stories of rapists using the threat of custody actions to blackmail and intimidate their victims into not pressing criminal charges.

“I got really lucky because the court terminated [my alleged attacker’s] parental rights anyway,” Prewitt says, “but I know a lot of women who aren’t so lucky.”

Rebecca Kiessling, the child of a rape victim, is a pro-life speaker and attorney who works closely with rape victims fighting custody cases. “It’s detrimental to both the mother and child to have the rapist involved,” she says.

Surely, most people would agree. So why don’t more states have protections in place for women who conceive children through rape?

Part of the problem is that many rapes go unprosecuted. According to the Rape, Abuse and Incest National Network, only 9 out of every 100 rapes are prosecuted and just 5 lead to a felony conviction. But of the 19 states that have laws addressing the custody of rape-conceived children, 13 require proof of conviction in order to waive the rapist’s parental rights. Two more states have provisions on the issue that only apply if the victim is a minor or, in one of those cases, a stepchild or adopted child of the rapist. Another three states don’t have laws that deal with custody of a rapist’s child specifically, but do restrict the parental rights of a father or mother who sexually abused the other parent.

In Maryland, which has no explicit statute in place, Democratic state Sen. Jamin B. Raskin has repeatedly tried to get a law passed preventing rapists from exercising parental rights under a standard used in civil court: preponderance of evidence, where a jury only has to be at least 51 percent sure the rape occurred. (Legally, this is two steps below the “beyond reasonable doubt” standard used in criminal proceedings.)

“I tried to base my bill on a civil standard because parental rights are a civil matter,” Raskin says. “The House took the position that you can’t say there was conception by rape unless there was a rape conviction.”

Raskin, who is also a law professor at American University, says several women testified before his Senate committee that they were subjected to continued harassment after their rapists asserted their parental rights.

“I think it’s scandalous that we would expose women to the possibility of continued abuse by a sexual aggressor,” he says.

While Maryland still hasn’t managed to pass a law, there has been some movement on this issue in other states in recent years: Oregon passed a conviction-based law in 2011, and Indiana passed a bill through the Senate in January of this year—but it was modified in the House to authorize an advisory committee to study the issue first.

Missouri, where Prewitt ran into trouble almost a decade ago, just passed a law that goes into effect later this month. It places an automatic stay on paternity proceedings when there is a pending criminal case alleging rape by the child’s father.

The woman behind the law is Angela Crews, a former Army MP whose teenage daughter conceived a son through alleged rape. The criminal case is pending, so she’s unable to go into detail, but Crews says she thought it was “crazy” that there was no law to explicitly stop a woman’s attacker from seeking custody during criminal proceedings. So, in 2011, she decided to do something about it: She found a local lawmaker to take up her cause and lobbied for Senate Bill 628.

Crews says that her ultimate goal is to get a law passed that prevents custody based on “clear and convincing evidence”—a higher standard than what Raskin proposed, but one that doesn’t require a criminal conviction.

“What I’m learning in my daughter’s case is that even getting a prosecution is so hard,” Crews says. “But this law is a start.”

Story by Dana Liebelson. Map and additional reporting by Sydney Brownstone.