Rep. Tammy Baldwin (D-Wis.) Center for American Progress Action Fund/FlickrIt’s breakfast time at the Larson Acres Dairy in rural Evansville, Wisconsin, and the line for hot-off-the-griddle pancakes and iced chocolate milk winds around the big barn, past the kids crawling in a bed of corn kernels, the live band tuning up, and out to the silver grain silos gleaming in the morning sun. June is Dairy Month in Wisconsin, highlighted by the weekend dairy breakfasts put on by farms across the state. On this Saturday, droves of sleepy-eyed cheeseheads descend on Larson Acres to eat, drink, buy T-shirts, and see the latest in milk-pumping technology.

Rep. Tammy Baldwin (D-Wis.) Center for American Progress Action Fund/FlickrIt’s breakfast time at the Larson Acres Dairy in rural Evansville, Wisconsin, and the line for hot-off-the-griddle pancakes and iced chocolate milk winds around the big barn, past the kids crawling in a bed of corn kernels, the live band tuning up, and out to the silver grain silos gleaming in the morning sun. June is Dairy Month in Wisconsin, highlighted by the weekend dairy breakfasts put on by farms across the state. On this Saturday, droves of sleepy-eyed cheeseheads descend on Larson Acres to eat, drink, buy T-shirts, and see the latest in milk-pumping technology.

But before the hungry masses get to the pancake tent, they have to get past Tammy Baldwin. The seven-term Democratic congresswoman representing Wisconsin’s second district is all smiles and handshakes, issuing a stream of Greetings! and Well, hello theres. Larson Acres is on Baldwin’s home turf, as evidenced by the number of people who simply call her “Tammy” and pledge to vote for her this fall in her bid to replace the retiring Democrat Herb Kohl in the US Senate.

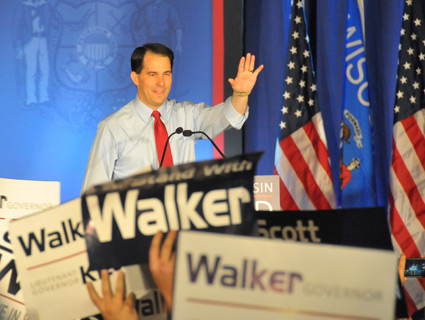

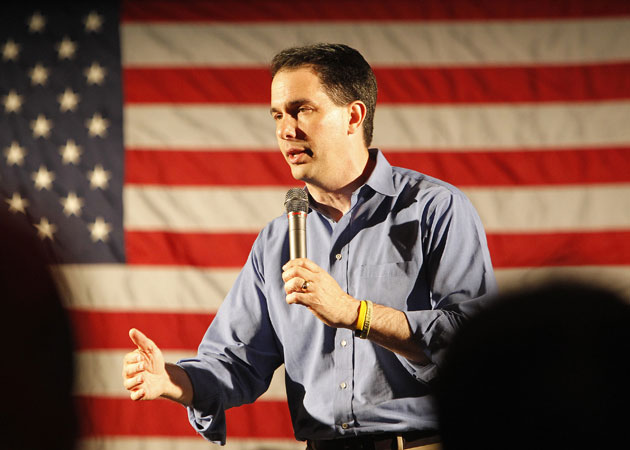

Wisconsinites joke that Dane County, which includes Madison, the state capital, is an oasis of liberalism “surrounded by reality.” Baldwin cut her teeth in politics here, and she can bank on its support in the first statewide campaign of her 27-year career. “Reality” is where she runs into trouble. If elected, Baldwin would be the first openly gay senator in the institution’s history. Yet can a gay Madison liberal win over Wisconsinites in the polarized, cash-drenched Scott Walker era?

Voters outside Dane County don’t outright dislike Baldwin (though a few million dollars in super-PAC attack ads could change that). It’s just that few of them know who she is: Ask voters in northern Wisconsin about her, and you’ll get blank stares and shrugs. Thirty two percent of voters responding to a recent Marquette University Law School poll had never heard of Baldwin. “You’d think that having been a member of Congress for a long time, she’d be known outside her district,” says Charles Franklin, a political scientist who oversees Marquette’s polling. “But that’s not the case at all.”

On a break from working the pancake line at Larson Acres, Baldwin previews how she’ll win over voters who don’t know her name. It’s not what you’d expect from one of Congress’ most liberal members. Gone are the impassioned calls for a single-payer health insurance system, tougher environmental regulations, and legalizing same-sex marriage.

Now Baldwin wants to talk about paper. Paper manufacturers employ more than 50,000 Wisconsinites—and Baldwin is tailoring her message to those people. “I’ve proposed policies to keep China from cheating the paper industry,” she tells me. She mentions the CHEATS Act, short for the China Hurts Economic Advancement Through Subsidies, which would impose new tariffs on Chinese paper imports. The Chinese government heavily subsidizes its paper-makers, she explains, putting Wisconsin paper plants at a disadvantage; the CHEATS Act would erase that disparity.

Wisconsin’s paper industry featured front and center in the Baldwin campaign’s debut TV ad. In it, Baldwin sounds almost like a dyed-in-the-wool tea partier. “In Wisconsin, we lead the entire nation in paper industry jobs,” she says. “But China, they lead the world in cheating.”

The choice to launch her TV campaign with a broadside against China and an appeal to blue-collar workers took some Wisconsin politicos by surprise. Franklin says it’s a gutsy move—and the right one in trying to appeal to white working-class voters. “You’re talking about someone stepping outside the stereotypes and representing herself in a way that is right up the alley of job creation,” he says. “I don’t think you can win on just the paper issue, but she’s chosen the issue that seems to me to have the potential for much broader appeal.”

Baldwin’s tough talk on China dovetails with her broader demand for tax fairness—not just in trade, but up and down the income ladder. “It’s about fairness, playing by the rules,” she tells me. “That’s how you get a vibrant middle class in Wisconsin.”

Baldwin’s blue-collar appeal also serves to deflect attacks on her liberal voting record. At Larson Acres, Baldwin reminds me that she introduced the CHEATS Act with Rep. Reid Ribble, a Republican who represents Wisconsin’s 8th district—a rural region where Baldwin needs to make inroads. In March, she cosigned a bill sponsored by conservative firebrand Rep. Michele Bachmann (R-Minn.) to a build a new bridge over the St. Croix River linking Minnesota and Wisconsin. And back in her state legislature days, Baldwin co-sponsored campaign finance disclosure legislation with then-State Assemblyman—now Governor and Republican hero—Scott Walker. “Hard to imagine now, isn’t it?” she quips.

Baldwin has less to say about her own story. She first dipped a toe into politics as a Dane County supervisor in the mid-1980s. Her 1992 election as the first openly gay member of the Wisconsin State Assembly catapulted her into the national debate over gay rights, HIV/AIDS, and gays in the military. Six years later she replaced outgoing Republican Scott Klug in the House of Representatives, becoming the first openly gay woman to win a congressional election. A win this November would make history once again.

In the past, Baldwin saw herself as clearing the way for other gay and lesbian politicians. “Sometimes I think my most significant contribution is not the legislative initiatives I introduce, but the stereotypes I shatter,” she told the Washington Times in 1993. She has also stressed that her openness about being a lesbian plays to her advantage. “I would get statements from voters such as, ‘If you can be honest about this, I believe you’d be honest about everything with me,'” she told the Toronto Star in 1995. By now, Baldwin’s sexual orientation is old news in Wisconsin, says Susan Johnson, a political scientist at the University of Wisconsin at Whitewater. “We’re at a point as a state and a country that that’s just not as important of an issue,” Johnson says.

No matter: Baldwin has plenty more to worry about. Her Republican opponent, former governor Tommy Thompson, is as much a household name as Packers quarterback Aaron Rodgers, and Thompson has consistently outpolled Baldwin.

Another factor: President Obama’s performance. If the Obama campaign invests heavily in the state to boost the president’s standing, it could lift every other down-ballot Democrat, including Baldwin. And a few million dollars more in outside money—super-PACs and nonprofits have already spent $850,000 attacking Baldwin—could inflict major damage. “She hasn’t been in a race where fundraising has been so important,” Johnson says. “I just think with the outside money, it’s such a wildcard.”

Johnson’s advice for Baldwin is simple: Take a map, circle every must-win region, and go “make herself a presence.” Close elections are won and lost at dairy breakfasts and county fairs, Brewers and Packers games, ice cream socials and Friday fish fries. No one knows that better than Baldwin. Her summer calendar has been packed with events everywhere from Wausau to Janesville to Rhinelander.

Indeed, the Larson Acres’s dairy breakfast is the first of many stops on this Saturday. Baldwin walks toward the parking lot, stopping to chat with anyone who’ll give her the time of day.

“Do you have any Packers schedules?” a round-bellied, middle-aged man asks her.

Baldwin glances toward a campaign aide. The aide shakes his head. “No, I’m sorry we don’t.”

“You always have Packers schedules at Dairy Breakfasts,” comes the reply. The man hustles off toward the pancake tent.

“Note to self,” Baldwin says to her team. “Bring Packers schedules.”