President Obama makes a statement about Hurricane Sandy at FEMA HQ in Washington on Sunday.Dennis Brack/MCT/Zuma

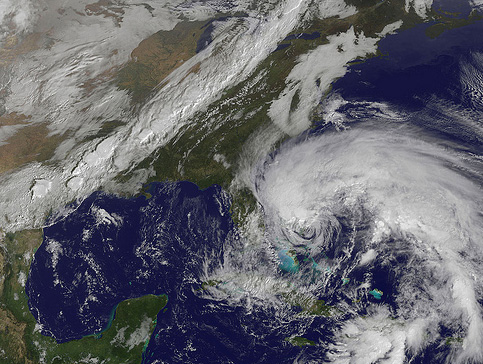

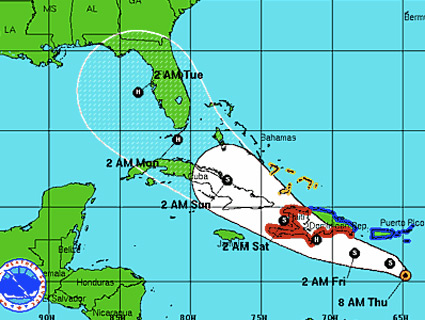

Hurricane Sandy, which is barreling towards America’s East Coast, is epic in scale—according to the National Weather Service, the storm reaches from Florida to Connecticut. But public safety problems from flooding, power outages, and property damage aren’t the only way the massive storm could affect your life: If Sandy turns out to be as bad as the meteorologists fear, it could have a real impact on the 2012 presidential election.

Political scientists have found that extreme weather affects how voters evaluate presidents and governors, and botching disaster response can dash incumbents’ reelection hopes. Andrew Reeves and John Gasper, political science professors at Boston University and Carnegie Mellon University, respectively, found that voters punish leaders for failing to react adequately to natural disasters—and reward those who respond effectively.

“Voters did in fact punish both governors and presidents for damage caused by natural disasters, but that that effect was really swamped by their response,” Reeves says. “[Voters] rewarded when governors [asked for] and presidents [gave] help, and they punished when they didn’t.”

It may seem bizarre that something like the weather would affect who lives in the White House come January. But freak events like Sandy aren’t the only kind of weather that affects voters’ decisions. There’s evidence voters even punish incumbents for harsh weather over the course of an election year, despite it being by definition out of politicians’ control.

“The pretty strong pattern turns out to be that all other things being equal, the incumbent party does less well when it’s too wet or too dry,” says Larry Bartels, a professor of political science at Vanderbilt University. In 2004, Bartels and his then-colleague Christopher Achen, who’s now a professor at Princeton, authored a study on the impact of climate on elections. According to their study, Al Gore lost an estimated 2.8 million votes to George W. Bush in certain states because of drought or excessive rain. These are votes, the study dryly points out, that Gore could have used.

The climate over the course of the past year (like the massive drought experienced by much of the county) is already baked into Obama’s reelection chances. But even though Mother Nature can swing an election, incumbents still have some control over their fates. How a president manages a crisis matters, according to Reeves—and how a president sells his management of a crisis can matter even more.

“Every president puts up pictures of himself with shirtsleeves rolled up comforting voters,” Reeves says. “I’m willing to bet that we’re going to see the White House put up a picture of Obama doing the same.” In this case, Reeves is right: On Friday, the White House sent out a photograph of President Obama on a conference call with officials from the Federal Emergency Management Agency and the National Hurricane Center.

But political theater can minimize the human cost of natural disasters and make a bungled response look even worse.

“There’s that iconic photograph of President Bush flying over New Orleans looking down from his plane: That was a case where framing and the action didn’t go so well,” Reeves says. Presidents’ approval ratings can decrease when the mismanagement of a natural disaster turns into a national event. But absent a national crisis, there are number of swing states in the path of the storm, including Virginia and North Carolina. How those states are able to cope with Hurricane Sandy could make a difference in who carries them on November 6.

“Especially because it’s happening so close to the election, probably the visible response of the administration to the situation is going to matter more than the situation itself,” Bartels says. In other words, how Hurricane Sandy affects the 2012 election is, at least to some extent, in Barack Obama’s hands.

“Most of the time these kinds of things I think are a boon for presidents,” Reeves says. “Machiavelli talked about [how] every crisis is an opportunity.”