<a href="http://www.flickr.com/photos/78428166@N00/7761818952/sizes/l/in/photostream/">Flickr/Tobyotter</a>

At last night’s vice presidential debate, Paul Ryan repeated a persistent conservative saw about the Obama administration’s plan to let Bush-era tax cuts expire for the rich. “Two-thirds of our jobs come from small businesses,” he said. “This one tax would actually tax about 53 percent of small-business income.” In the first presidential debate, Mitt Romney struck the same chord, saying that Obama’s plan to make wealthy individuals pay Clinton-era taxes was in fact an attack on “the people who work in small business.”

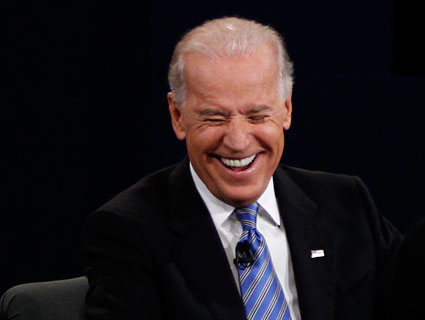

The rhetorical appeal is clear: Americans love small businesses. My dad runs one; I do, too. But Ryan and Romney aren’t talking about my family, or really any of the mom-and-pops across the country. They’re talking mainly about corporate bigwigs and investment firms hiding behind the same tax structures my dad and I use to start a nest egg. They’re redefining hedge fund managers, Fortune 500 corporations, and multinational beer empires as small businesses. That’s a load of malarkey—and it hits close to home for me.

How does the conservative argument work? Here’s a history.

Both sides can trace this debate back to a 2010 report by the Joint Committee on Taxation, which gauged the consequences of Obama’s tax proposals. When it came to the big idea—keep low Bush-era tax rates for middle-class earners, but let those making $250,000 or more pay at the old Clinton-era tax rates—the committee praised the plan: “The proposal provides tax relief to a large percentage of taxpayers, which will provide incentives for these taxpayers to work, to save, and to invest and, thereby, will have a positive effect on the long-term health of the economy.”

When it came to those high earners, though, the committee noted that their taxes would indeed rise, and “[o]pponents of this latter aspect of the proposal often note that many small businesses, and a large fraction of small business income, will be adversely impacted by an increase in the top two tax rates.” Was that argument true? Not really, the report continued:

The staff of the Joint Committee on Taxation estimates that in 2011 just under 750,000 taxpayers with net positive business income (three percent of all taxpayers with net positive business income) will have marginal rates of 36 or 39.6 percent under the President’s proposal, and that 50 percent of the approximately $1 trillion of aggregate net positive business income will be reported on returns that have a marginal rate of 36 or 39.6 percent. These figures for net positive business income do not imply that all of the income is from entities that might be considered “small.” For example, in 2005, 12,862 S corporations and 6,658 partnerships had receipts of more than $50 million. [emphasis added]

When you peel back the bureaucratese, what this says is: Half of all the money made by small businesses is actually made by just 3 percent of the small businesses. How is that possible? Because not all “small businesses” are actually small. The report singles out “S corporations” and “partnerships.” These are “pass-through” structures, corporate tax entities whose names have become synonymous with small business, irrespective of how many employees you hire, or how much money you make. And that’s where the true problem lies.

A quick backstory: In the ’80s, my dad—a boat mechanic, and a seventh-grade dropout—made the scary decision to leave his employer and branch out on his own. He incorporated his business as an S corporation, a structure that enables little guys and family operations to pay their modest expenses and “pass through” the remaining business profits as personal income. He’s an assiduous record-keeper, paying estimated taxes to Uncle Sam every quarter. Some years, there are no profits, and no taxes. Other years, he does pretty well. He’s never had a six-figure haul. Like him, I set up an S corp, to handle my occasional freelance writing. The profits are usually enough to pay for a weekend outing and the family pets’ annual shots.

The way the tax codes are structured, practically any individual who’s earning freelance or self-employment income can incorporate himself as an S corp. There are good reasons for doing so—avoiding paying corporate and payroll taxes when you don’t actually have any employees on a payroll, for example. But major corporations, too, have figured out how to shelter their profits in these havens. In 2007, for example, 339 manufacturing corporations that each pulled in an average of $429 million filed as “small business” S corps…and paid zero corporate taxes. (By contrast, the 4,375 manufacturers that filed as actual corporations made a just over a tenth of that amount, and paid an average of about a million in corporate taxes.)

Back in 2010, MSNBC’s Keith Olbermann dedicated an entire show segment to major corporate entities that use pass-through loopholes to pay taxes as small businesses. They included:

- Enterprise Products Partners, L.P., a Fortune 500 pipeline company worth $34 billion whose PAC gives generously to Republicans.

- Kohlberg Kravis Roberts & Co., the original “Barbarians at the Gate,” a buyout firm worth $61.5 billion that is currently accused of working with Romney’s old firm, Bain Capital, and others to rig bids for companies they wanted to flip.

- Price Waterhouse Coopers, the accounting firm. (Ironically, six years before getting called out for its own pass-through loophole, a PWC economist concluded that the federal government’s relatively low tax revenue from business “is explained by the unusually high share of U.S. business income earned through passthrough entities.”)

- CoorsTek, a spinoff ceramics company founded by beer tycoon Adolph Coors that “owns and operates 44 facilities on four continents.” CoorsTek’s “Vice President, Tax” is a board member on the S Corporation Association, an industry lobby group. (Its motto: “Defending America’s Small and Family-Owned Businesses.”)

- McIlhenney Co., the Tabasco maker, with $250 million in revenue in 2007. Their president is the S-corp lobby’s chairman.

“There is no obvious definition of small business. It’s all a matter of judgment,” writes Martin A. Sullivan, chief economist for the nonprofit watchdog Tax Analysts. But, when you look at the data, it’s clear “that a significant portion of profits that escapes [corporate] taxation accrues to businesses that are not small by anybody’s definition.”

When Republicans complain that small businesses will take a tax hit under Obama, they primarily mean these guys, not me or my dad. “[O]bviously, the top 3 percent have half of the gross income for those companies that we would term small businesses,” GOP House Majority Leader John Boehner said in 2010. “And this is why you don’t want to punish these people at a time when you have a weak economy.”

If John Boehner and the principals of Kohlberg Kravis Roberts & Co. want to see real punishment, they should visit some real small business owners, like my pop—who, at 55, still contorts himself into yogic positions in dirty bilge water to hand-tighten exhaust manifolds on boat engines, and who has never been able to afford health insurance for himself and my stay-at-home mother. Then, instead of offering him corporate-friendly doublespeak and macroeconomic trickle-down fantasies, maybe conservatives could give my dad’s business a real hand.