<a href="http://www.flickr.com/photos/gageskidmore/">Gage Skidmore</a>/Flickr; Medyan Dairieh/Zuma

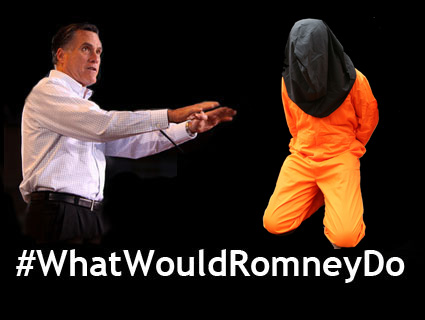

When it comes to civil liberties and national security, the two major party candidates for president on the ballot Tuesday don’t offer much of a choice.

“Regardless of who the next president is,” says Hina Shamsi, director of the ACLU National Security Project, “it must be up for debate in the next administration whether a global war-based approach is worth the costs to lives, American values, and our standing in the world.”

It may not be. If Mitt Romney wins on Tuesday, a lot of things could change: Medicare could be turned into a voucher system; Medicaid could be substantially cut. Any Supreme Court vacancies would be filled with conservative jurists hostile to abortion rights, attempts to rectify racial inequality, or rein in the influence of money in politics. The Affordable Care Act, which will guarantee health insurance coverage for millions of Americans, could be toast.

But the expansion of the American national security state will likely remain unimpeded by whomever sleeps in the White House on January 20.

“We’ve basically reached a general consensus, both political and legal about where we are,” says Harvard law school professor Jack Goldsmith, who worked in the Bush Justice Department’s Office of Legal Counsel. “I think that consensus explains why Obama continued Bush’s policies, and why the policies will continue no matter who gets elected president.”

Barack Obama came into office promising to reform the PATRIOT Act, rein in Bush’s warrantless surveillance, ban torture, and close Guantanamo. His torture ban remains in the form of a fragile executive order, many detainees at Gitmo have little hope of trial let alone release, and renewal of the PATRIOT Act steamrolled through Congress with the administration’s support absent even the mild reforms civil-liberties-minded senators proposed. Obama said he’d only rarely use the state secrets doctrine to block national security policy from court scrutiny, but he’s used it much the same way as his predecessor. Obama broke his own promise not to go to war without Congress when he intervened on behalf of anti-Qaddafi rebels in Libya, and Romney thinks he could do the same with Iran. While targeted killing began under Bush, Obama has expanded the covert global war on terror dramatically, even to the point of deliberately targeted American citizens.

There’s no reason to think Romney would significantly change any of this.

“[Drone] technology—and its ability to limit American military casualties on the ground—is driving the policy regardless of who sits in the Oval Office,” Yale Law professor Jack Balkin says. “It’s unlikely that Romney would be better than Obama on civil liberties or human rights issues; he might be worse.”

As far as drones are concerned, Romney already made himself clear during the third debate. “We should use any and all means necessary to take out people who pose a threat to us and our friends around the world,” Romney said when asked about the use of drone strikes. “And it’s widely reported that drones are being used in drone strikes, and I support that…entirely.”

During the campaign Romney hasn’t expressed an ounce of skepticism over the PATRIOT Act or the government’s use of warrantless wiretapping. He wanted to “double Guantanamo” as a candidate in 2007, but Romney’s shifting positions leave what he’d do with the offshore detention camp a mystery. But regardless of who wins, it’s unlikely to close because of restrictions Congress has placed on the president’s ability to transfer detainees. Romney has struggled all year to get to Obama’s right on foreign policy, but his most consistent criticism is that the administration has leaked too much information related to national security, which means it’s unlikely he’d be any less secretive than the current president.

“There is a bipartisan consensus on most aspects of the national surveillance state,” Balkin says. “At this point, you shouldn’t expect either party to cut back on its essential attributes.” Democrats who might have opposed certain policies with a Republican president in office have mostly fallen in line.

There could be some differences on the margins, experts say: Obama may try harder to close Gitmo in his second term, and Romney might decide to subject future terror suspects to indefinite detention. Romney might not have the same default preference for civilian trials of terror suspects that Bush and Obama had. But there’s little reason to expect the trajectory of American national security policy to change, absent intervention from the courts or a serious change of heart in Congress.

It’s easy to set the blame for this state of affairs on Bush’s disdain for the law or Obama’s cowardice. We like stories with simple explanations and obvious villains. The dirty little secret though, is that this is how Americans want it. Support for aggressive counterterrorism measures has only grown since 9/11, but beyond the polls the simple fact is Americans can tune out thousands of deaths a year from car accidents or disease but even a failed terror attack that kills no one can generate enough hysteria to lead to drastic changes in American law.

Americans don’t just have the government they deserve, they have the one they want, at least for now. Since 2004, support for the PATRIOT Act has increased. Use of drones to kill suspected terrorists remains popular, and most Americans want Gitmo to stay open. Even torture has grown more popular since Obama banned it by executive order. Romney’s advisers drafted a memo recommending a return to Bush-era interrogation techniques, but bringing those back would be more difficult than it sounds: According to Goldsmith, most of the harshest techniques are illegal under laws passed by Congress and court decisions issued while Bush was still in office.

“Just as Obama didn’t change much from Bush,” Goldsmith says, “Romney, if he gets in there, will realize he doesn’t have nearly as many options for change as he thinks he does.”