Smith & Wesson's "Dirty Harry moment," 1971Warner Bros.

Once a year the Austrian gun manufacturer Glock puts out a glossy, full-color magazine called Glock Autopistol, packed with buyer’s guides for new items, like the G22 Gen4 with tactical laser light, and interviews with celebrity endorsers.

It also publishes movie reviews.

“Angelina Jolie sure does love GLOCKs,” writer John Fasano gushed in a 2011 wrap-up of movies featuring the company’s products. “She lit up the screen with her G18 in the family hit man actioner Mr. & Mrs. Smith and hit last summer’s multiplexes as a CIA agent who has to go on the run when she is accused of being a Russian spy in [Evelyn Salt]. Any GLOCK aficionado worth their salt knows that when Angelina shares the scene with the Austrian super gun it’s hard to know where to look!”

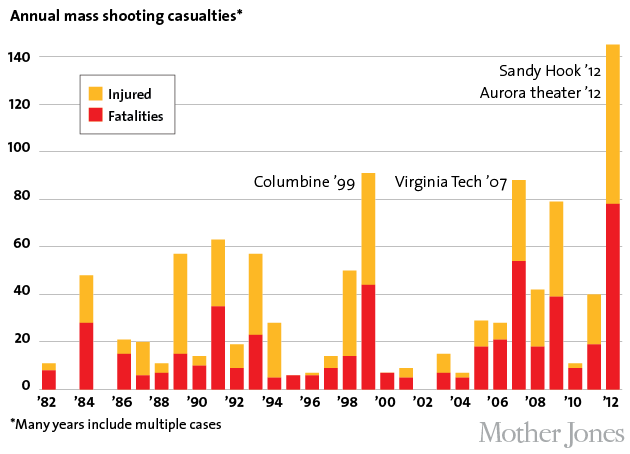

The company’s warm embrace of pulpy action films underscores one of the gun industry’s dirty secrets. In the wake of December’s massacre at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, Connecticut, National Rifle Association executive vice president Wayne LaPierre called body count blockbusters like those praised in Autopistols “the filthiest form of pornography.”

But that “pornography” has been a blessing to companies like Glock—and in turn, they’ve pulled strings to make sure their products end up on screen. As Guns & Ammo magazine put it in an oft-cited 1984 story, “TV and motion picture guns create powerful, unforgettable images that have had a measurable impact on the shooting world.”

Indeed, way back in 1959 a Sports Illustrated article attributed the resurrection of the Colt .45 to a glut of new spaghetti westerns. Colt had ceased production of the gun by 1940, but by the late 1950s it was selling 150,000 units per year thanks, in part, to the movies. Dirty Harry clearly bolstered Smith & Wesson sales in the 1970s. And Park Dietz, a California-based criminologist who studied the impact of media on commercial firearm sales, would later tell Cox News Service that “the major determinant of assault-gun fashion for the 1980s” was whatever appeared on Miami Vice. (Among other things, the show caused the price of the Bren Ten—Sonny Crockett’s weapon of choice—to skyrocket, since that company had already folded.)

The Glock story offers an apt case study for how gun manufacturers use shoot-em-up flicks to flog their brands. In Glock: The Rise of America’s Gun, reporter Paul Barrett argues that the ubiquity of the Austrian pistol was in part a consequence of the business boom Smith & Wesson experienced after its .44 Magnum was treated to its extended Clint Eastwood soliloquy. Glock, Barrett explained, wanted “its Dirty Harry moment.”

So it began offering firearms on the cheap, if not free, to Hollywood prop houses, the specially licensed firms that provide weaponry and training for movie sets—in some cases, it even prioritized shipments to the prop houses at the expense of actual gun retailers, according to Barrett. “Lots of ‘film-friendly’ companies hand out product at low or no cost to get into movies—and it works,” noted Rick Washburn, founder and president of prop house The Specialists Ltd., in a 1999 interview.

On screen, Bruce Willis and Mickey Rourke flicks touted a Glock’s (nonexistent) ability to avoid metal detectors. Tommy Lee Jones contrasted the weapon with “sissy pistols” while extolling its all-weather durability to Robert Downey Jr. in 1998’s U.S. Marshals. Pretty soon, the gun was everywhere. In 2010, Brandchannel, a website dedicated to spotting product placement, gave Glock a lifetime achievement award after it appeared in more than 15 percent of that year’s box-office-topping films.

Glock wasn’t alone. In the late 1990s, Smith & Wesson, looking to recapture its own Dirty Harry magic, briefly hired a firm called International Promotions, which specializes in product placement, to work with movie studios to get its product on screen.

Magnum Research, which manufactures the long-barreled Desert Eagle used by agents in The Matrix, eschewed a formal product placement push, but it cultivated a close relationship with the prop houses, too. A 1994 Minneapolis Star-Tribune story captured Magnum president John Risdall courting Hollywood arms suppliers at a Dallas trade show. Magnum even set up a website, Magnum Films, to detail the films—including Austin Powers and the 1996 Pamela Anderson joint Barb Wire—that featured its weapons. (There’s even an IMDB copycat wiki called IMFDB—Internet Movie Firearms Database.) “At a certain level, your product is at a point in the social consciousness where people recognize what it is,” Risdall told the Baltimore Sun. “And the movies give us an opportunity, as do the TV shows, to get to that point.”

The market has changed quite a bit since the booming 1990s. Smith & Wesson stopped working with International Promotions after the press got wind of the relationship. And, as the New York Times reported in December, gun manufacturers have focused a larger share of their efforts on first-person shooter video games like Call of Duty, which offer them a more direct way to reach potential buyers. For the most part, the prop houses now buy their own weapons, with no special offers. “On rare occasions they’ll give us a good deal on stuff because it’s a new model,” says Gregg Bilson, founder of the prop house Independent Studio Services. Ryder Washburn, vice president of The Specialists Ltd., says his father’s prop house gets “dealer pricing,” and on rare occasions an additional 10 percent discount. The big gunmakers don’t really have to sweeten the deal anymore. They’ve already won.

The film industry’s complicity in promoting guns doesn’t necessarily make it complicit in promoting gun violence. (No study has ever demonstrated a connection between on-screen and off-screen shootings.) But gun manufacturers’ courtship of Hollywood does betray efforts by the NRA and other Second Amendment activists to blame massacres like Sandy Hook on media-fueled cultural decay. Bilson says he recently gave the NRA a piece of his mind on that subject: “We were kind of thrown under a bus there.”

Yet he takes comfort in the fact that LaPierre’s “pornography” bluster is little more than just that. “They will never regulate violence in movies,” Bilson says. And that’s a win-win—for filmmakers and gunmakers alike.