<a href="http://electmarbut.com/">electmarbut.com</a> & <a href="http://www.shutterstock.com">Stephanie Frey</a>/Shutterstock

Gary Marbut has a dream: a single shot, bolt-action, made-in-Missoula, .22 caliber rifle called the Montana Buckaroo. For the time being, the Buckaroo, adapted from an expired 1899 patent and intended for use by small children, exists only on paper. “Our attorneys have insisted that I NOT complete EVEN ONE Buckaroo,” Marbut told me in an email on Monday.

That’s because Marbut’s real target isn’t the 5- to 10-year-old demographic*—it’s the United States Supreme Court. His goal is to effectively nullify decades of federal gun law, and he thinks he’s found a trick no one else has tried. In 2009, Marbut pushed a law through the Montana Legislature asserting the state’s partial immunity from federal gun regulations, and then sued the Department of Justice for the right to follow through. Under his scheme, the federal government would be helpless to regulate firearm production or distribution—so long as the guns in question never cross state lines.

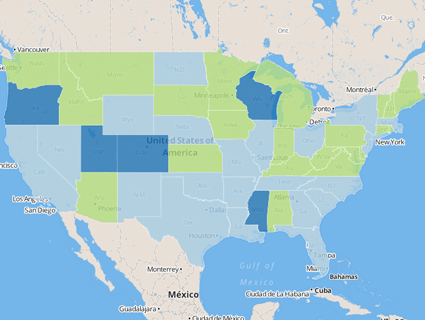

Lawmakers in 34 states have introduced copycat versions of Marbut’s Firearms Freedom Act, six of them in the five weeks since the massacre at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, Connecticut. All told, nine state attorneys general have signed onto an amicus brief supporting him; eight governors have signed it into law. The National Rifle Association supports Marbut’s law; so does the Cato Institute.

A gun safety instructor who manufactures shooting targets for use by police departments, Marbut moonlights as an unpaid lobbyist in Helena—an incredibly successful unpaid lobbyist. As president of the Montana Shooting Sports Association, he has personally written 58 pieces of legislation that have been signed into law dating back to 1987, ranging from a measure removing wolves from the state’s protected species list to a law guaranteeing the “immunity of certain firearms safety instructors” from liability. But the Montana Firearms Freedom Act is by far his most ambitious project.

Marbut’s basic argument is that the federal government cannot regulate firearms manufactured and retained in a single state, because there is no “interstate” commerce involved. Therefore, under the 10th Amendment, only Montana—not Washington, DC—has the power to regulate these guns. (His argument doesn’t hold for sales across state lines.) That in itself is extraordinarily literal, and—as Marbut readily acknowledges, quite radical; even Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia thinks the federal government can regulate the plants you grow in your backyard.

Article I of the Constitution gives Congress the power to “regulate Commerce with foreign Nations, and among the several States, and with the Indian tribes”—a clause that has been used by the federal government over the last century as a means to regulate everything from medical marijuana to health insurance to, yes, guns. To win his case, Marbut has to convince the courts to ignore all that.

Shortly after his law passed in 2009, Marbut informed the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives of his desire to begin manufacturing the Montana Buckaroo. After the ATF told him he couldn’t move forward without a federal license, he filed suit against Attorney General Eric Holder, arguing that the ATF was breaking the law by preventing him from making the Buckaroo. He lost in district court, but immediately appealed.

The Brady Center to Prevent Gun Violence, joined by a coalition of law enforcement groups, argued against Marbut’s law on appeal, calling it a “dangerous threat to public safety and national security.” If the law held, they contended, it would allow Montanans to skirt the federal background check system, thereby making it easier for prohibited persons to obtain firearms. It would also allow in-state manufacturers to make and sell armor-piecing bullets, because Montana doesn’t have a law of its own prohibiting them.

The odds of a court coming over to Marbut’s side are daunting, for sure. Although he was heartened by Chief Justice John Roberts’ narrow reading of the Commerce Clause in validating the Affordable Care Act (for which Marbut submitted his own amicus brief), he concedes that upholding his law would entail a reversal of eight decades of established precedent.

In January, as state legislatures pushed ahead on Marbut-like draft legislation, Marbut got some good news: The 9th Circuit will hear oral arguments on his appeal in March. He doesn’t think the appeals court will accept his argument, but it doesn’t matter. It brings him one step closer to his ultimate goal—the Supreme Court.

In the meantime, he’s fast at work on a pair of new projects—two bills that would prohibit state and local law enforcement officials from enforcing any new executive orders on guns, and legislation to ban federal officers from seizing guns in Montana without permission from a county sheriff. He also recently developed a type of nonlethal “pillow” ammunition (comprised of bean-bags filled with lead shot) that he says is ideal for fighting off bears. But after a wildlife biologist inquired about purchasing the pillow ammo, Marbut turned him down. “I said, ‘No, I can’t because I don’t have a federal license for making and selling ammunition,'” he recalls.

There’s nothing legally preventing him from obtaining such a license. It’s just a matter of principle.

*Correction: This article originally suggested the Montana Buckaroo might be used for skeet-shooting. It is exceedingly difficult to shoot skeet with a rifle; the weapon of choice is a shotgun.