United States Fish and Wildlife Service via Wikimedia Commons

A team of leading polar bear ecologists called for nations to make plans now for dealing with ongoing—and soon to be critical—threats to the survival of polar bears. The biggest problem for this iconic Arctic species is the mindblowingly fast disappearance of sea ice. Their paper appears in Conservation Letters.

For instance, last month (January 2013) the average coverage of sea ice in the Arctic Ocean was 409,000 square miles (1.06 million square kilometers) below the 1979 to 2000 January average. That’s the sixth-lowest January extent in the satellite record, says the National Snow & Ice Data Center. Plus 2012 saw the lowest ever summer coverage of sea ice in the Arctic.

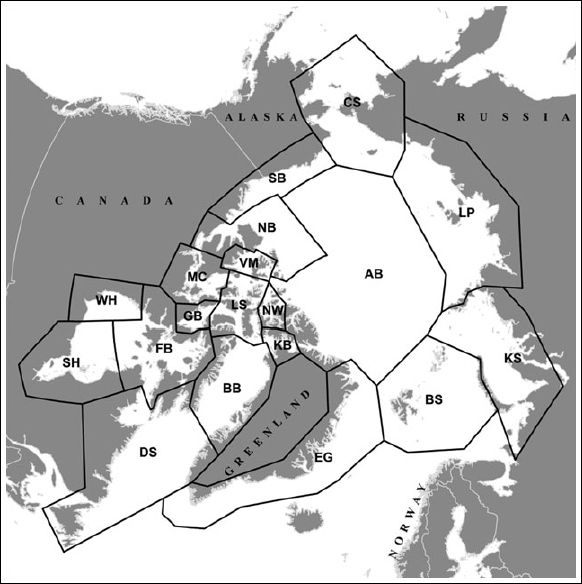

It’s not going to be easy to mitigate these challenges, the authors warn. There are 19 populations of polar bears worldwide. Some—like the Western Hudson Bay (WH, in the map above) bears and the Davis Strait (DS) bears—experience complete sea ice melt in summer that forces them onto land where they’ve got nothing to eat and can only burn through their own fat until the ocean refreezes.

For other populations—the Chukchi Sea (CS), Laptev Sea (LS), and Barents Sea (BS)—many bears remain on drifting pack ice and multiyear ice year round. The problem is that a lot of that pack ice is now retreating far beyond the continental shelf where ocean productivity is higher and polar bear prey more numerous. Meanwhile multiyear ice is disappearing rapidly throughout almost all the Arctic.

Here’s what we know happens to bears forced ashore for too long in summer, or kept far offshore on multiyear ice:

- declines in body condition

- declines in body size

- declines in reproductive rates

- declines in survival rates

- declines in population size

- declines in sea ice denning habitat

- altered movements and distribution

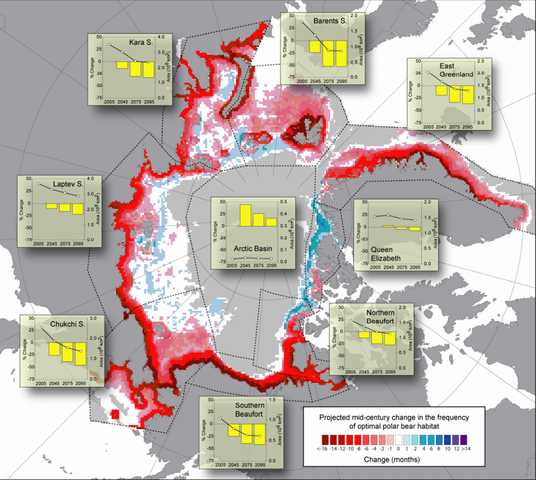

How bad will it get? In an earlier paper one author predicted the extinction of polar bears in two thirds of their range by 2050. That’s because low ice years will increase as long as greenhouse-gas-induced warming continues—until almost all years will be bad for polar bears. For example:

- Adult male mortality from starvation is predicted to increase to 28-48 percent in any year when the fasting period is 30 days longer than in recent years.

- The possible effects on other age and sex classes have not been modeled but are predicted to be more severe.

- Some years will continue to be better for polar bears and others poorer, even as the frequency of poor years increases until all are poor years.

- The first occurrences of exceptionally poor years are likely to present a near-term critical challenge to polar bear conservation.

The authors write:

When superimposed over the long-term declining trend, annual variability in sea ice makes it increasingly likely that we will soon see a year where sea ice availability for some polar bear populations is below thresholds for vital-rates. Malnutrition at previously unobserved scales may result in catastrophic population declines and numerous management challenges.

If you have the stomach for it, there’s a desperately tragic video of a polar bear mother and her two cubs dying of starvation here. Be forewarned: this is graphic and ghastly. But it’s also a sign of what’s happening now and what’s to come for many many more bears in the future. Knowledge of these kinds of events was one of the reasons this paper was written, lead author, and author of Polar Bears: A Complete Guide to their Biology and Behavior, Andrew Derocher told me.

It’s not just about bears either. Starving bears forced ashore are already a threat to local communities and that’s only likely to get worse in the near future. The authors write:

The most intensive program for dealing with human-bear interactions, the Polar Bear Alert program in Churchill, Manitoba, Canada, includes extensive hazing, relocation, and temporary housing of bears to mitigate conflict during the ice-free period. That program is expensive and may not be easily applied in small northern communities with limited resources. Nonetheless, we encourage alternatives to killing problem bears, which is a common outcome in northern communities. The Churchill program was established before the effects of climate change were recognized and it is unclear whether it will remain adequate as warming continues. Bears temporarily held in captivity are not currently fed so the cost of temporary holding will increase when the ice-free period extends beyond the fasting capacity of captive bears. Less-expensive options such as reducing attractants and securing storage of food should be included along with plans for increased deterrent capabilities. Training and equipping community polar bear monitors, along with extensive public education and inter-jurisdictional agreements, should be planned to help assure human safety.

Derocher also pointed me towards this successful World Wildlife Fund Canada project to protect villagers from hungry, shore-bound bears in the Hamlet of Arviat, Nunavut.

Among the authors’ other concerns:

- Polar bears are still hunted throughout the Arctic except in Norway and Russia. “Existing harvest management methods are inadequate for declining populations that, by definition, have no sustainable harvest.”

- Feeding some bears might become necessary to keep people safe. “Diversionary feeding could be a viable short-term tool to draw bears away from settlements or industrial facilities.” But possible negatives include: “the potential for disease and parasite transmission as well as human-wildlife conflicts may increase as other species such as Arctic fox, wolves, and grizzly bears are drawn into diversionary feeding locations?.”

- Feeding might also be needed to keep bears alive in areas where they might not otherwise survive. [How sad is that?]

- Some bears might need to be sent to high-quality zoos for captive breeding.

- Some bears might need to be euthanized if they’ve starved beyond rehabilitation.

The authors conclude:

Considering the global attention paid to polar bears, managers will be forced to respond to sudden changes in environmental conditions that negatively affect polar bears. We believe that managers and policy makers who have anticipated the effects, consulted with stakeholders, defined conservation objectives, created enabling legislation, and considered possible management actions will be most able to effectively respond to large-scale negative changes.

Andrew Derocher told me: “One thing we try to make clear is that we don’t necessarily recommend any of these options but lay them out for consideration and discussion. Further, we don’t view these desperate measures as a replacement for dealing with greenhouse gasses. If we don’t deal with climate change we won’t have any polar bear habitat left.”

- Andrew E. Derocher, Jon Aars, Steven C. Amstrup, Amy Cutting, Nick J. Lunn, Péter K. Molnár, Martyn E. Obbard, Ian Stirling, Gregory W. Thiemann, Dag Vongraven, Øystein Wiig, Geoffrey York. Rapid ecosystem change and polar bear conservation. Conservation Letters (2013). DOI:10.1111/conl.12009