Audience members take pictures at a presidential town hall meeting moderated by Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg in April 2011.<a href"http://www.whitehouse.gov/blog/2011/04/21/president-s-facebook-town-hall-budgets-values-engagement">The White House</a>

Sen. Jay Rockefeller IV (D-W.Va.) plans to retire next year after nearly three decades in public office. But first, he’s making a last-ditch effort to protect Americans’ privacy in the digital age by reintroducing his “Do-Not-Track Online” Act. The bill would give consumers, as Rockefeller puts it, “the opportunity to simply say ‘no thank you’ to anyone and everyone collecting their online information” and would slap heavy fines on companies that steal your information.

Yet online watchdogs say that so long as privacy policy is dominated by the whims of Silicon Valley and politicians themselves use data tracking to raise campaign cash, this effort is a long shot. “While it’s good that Sen. Rockefeller reintroduced the bill, everyone recognizes he’s a lame duck, and it won’t pass,” says Jeffrey Chester, executive director of the Center for Digital Democracy. “Washington won’t pass a privacy bill until John Boehner’s bank account is wiped out by hackers and Mark Zuckerberg defriends President Obama.”

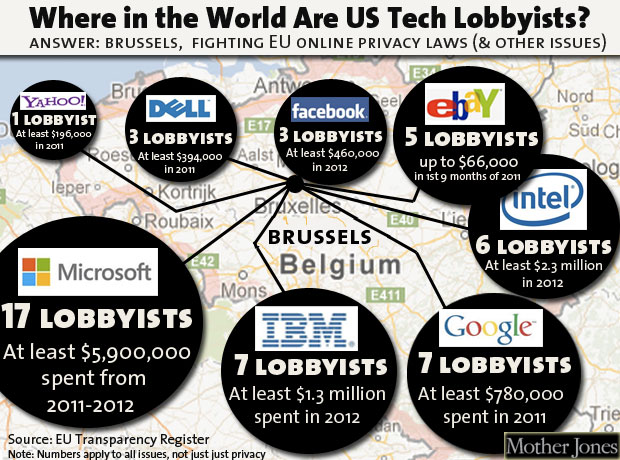

Lee Tien, senior staff attorney with the Electronic Frontier Foundation, agrees, noting that tech companies like Google, Yahoo, and Facebook have been focused on watering down stronger privacy laws in the European Union. “Advertisers and industry are much more engaged on the EU laws, because they are actually moving,” Tien says. “The US is a long way from passing a major privacy bill.”

defriends President Obama.”

Rockefeller, the chair of the Senate commerce committee, first proposed his bill in 2011. According to the New York Times, he did not push this version to the full Senate because companies promised to voluntarily respect users’ privacy, in part by following standards set by the World Wide Web Consortium. The voluntary plan “has failed pretty miserably,” says Kevin McAlister, a spokesman for Rockefeller.

“Do Not Track” would require companies to honor a consumer’s decision not to be monitored as he or she navigates through cyberspace, including on mobile phones, and gives the Federal Trade Commission the authority to issue fines of up to $15 million. The bill takes aim at companies like Acxiom and Experian that stalk your every online move and sell that information to companies like Facebook, so they can better target their advertisements. As ProPublica‘s Lois Beckett explains, data brokers sell information about everything from “whether you’re pregnant or divorced or trying to lose weight.” If you just read 18 wedding announcements on the New York Times site, for example, Facebook knows that—but you might not know that until the engagement ring advertisements start popping up on your Facebook profile page. Do Not Track would hypothetically block involuntary data sharing like that. But if you change your Facebook relationship status to “engaged,” this bill can’t help you—that’s voluntary information-sharing.

Chris Calabrese, legislative counsel at the American Civil Liberties Union, told IDG News Service, “If consumers don’t have the ability to opt out, the result is going to be a detailed portrait of our online activities, and that portrait will be outside our control.” Aleecia McDonald, director of privacy for the Stanford Center for Internet and Society, agrees that “Coming to a common understanding of ways to put users in control of their online experience through Do Not Track would be better for all stakeholders.” (Companies who run the web browsers, like Mozilla and Apple, tend to side with the privacy advocates.)

Although Google, Yahoo, and Facebook have yet to publicly weigh in on Rockefeller’s bill, when a similar “Do Not Track” bill was introduced in California by Democratic State Sen. Alan Lowenthal in 2011, these companies and dozens of others signed on to a letter calling the bill “unnecessary, unenforceable and unconstitutional.”

Daniel Castro, a senior analyst for the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation who opposes the bill, says that “receiving targeted ads is how consumers pay for free access to content and services,” and consumers should simply “not use services that they think don’t respect their privacy.” In other words, if you don’t want to be watched, don’t go to sites that watch you.

There’s one final obstacle for Rockefeller: His fellow lawmakers are already using online data tracking to collect information about their constituents. “We just came out of a campaign season that saw a huge emphasis on the use of targeted advertising to reach voters,” says Castro. “I suspect this legislation would gather much more support if it carved out exemptions for tracking for political campaigns.” Chester notes, “President Obama is using the same techniques that the data brokers and others are being accused of…How can we expect Washington to protect consumers, when invading privacy is good for electoral prospects?” That’s a question that Rockefeller doesn’t have to worry about.