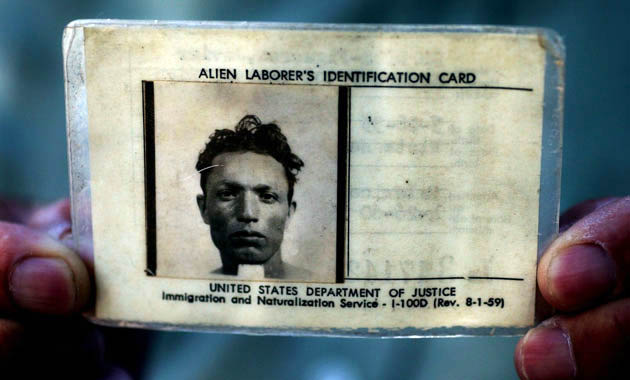

Javier de Dios Figueroa still carries the labor identification card he was issued in 1960.Jose Luis Villegas/ZUMA Press

The recruiter promised Ana Rosa Diaz three things before she came to the United States from Mexico to work for CJ’s Seafood: She’d be peeling crab, she’d be making $8.53 an hour, and she’d be working for six months out of the year.

Instead, Diaz ended up peeling crawfish in a cramped room with about 40 other workers until her nails were torn off, was paid by the pound instead of the hour with no overtime, and was sent home after only about five months. Even so, she was desperate. The money wasn’t what she was promised, but it was good enough that she talked a friend, Martha Uvalle, into joining her a few years after she first left for Louisiana in 2003. Diaz and Uvalle both had families to think of—Diaz has four children and Uvalle has five. So every year, they’d relocate to Louisiana and live in a trailer park for five months, peeling crawfish from five in the morning until three in the afternoon six days a week until they were sent home.

Diaz and Uvalle were temporary guest workers—a term that in the United States encompasses an alphabet soup of government visas that provide firms with access to foreign labor. Immigration reform advocates see the fate of the 11 million unauthorized immigrants in the United States as the great moral question of comprehensive immigration reform. But the thornier policy question, at least from the point of view of those who want to prevent another wave of illegal immigration to the United States, is how to meet the domestic demand for foreign labor legally while preventing those workers from being exploited.

“The reason we have 11 million unauthorized people living in America is that we have jobs for them to do but no legal way for them to get here,” says Tamar Jacoby, president of ImmigrationWorks USA, a right-leaning pro-immigration group. “Americans get that they don’t want their kids to cut lettuce, but they don’t want their kids to clean bedpans either.”

Many policy experts say the 1986 immigration reform bill failed to prevent the illegal immigration wave of the 1990s because it didn’t adequately account for the demand for foreign labor. If this year’s immigration reform bill lacks an effective program to channel that demand, they argue, the undocumented population will balloon again.

“If we want to have a different picture for the future, then its very much in our best interest to figure out a way for people to come legally,” says Doris Meissner, former commissioner of the Immigration and Naturalization Service and current director of the Migration Policy Institute.

That’s harder than it sounds. More than a year and a half ago, Sens. Chuck Schumer (D-N.Y.) and Lindsey Graham (R-S.C.) asked Thomas Donohue, the CEO of the Chamber of Commerce, America’s big business lobby, and Richard Trumka, president of the AFL-CIO, the largest union federation, to try to work out a deal on guest workers that would be acceptable to both unions and business interests. Staff experts from both sides then worked on a potential deal in advance of the current immigration reform push.

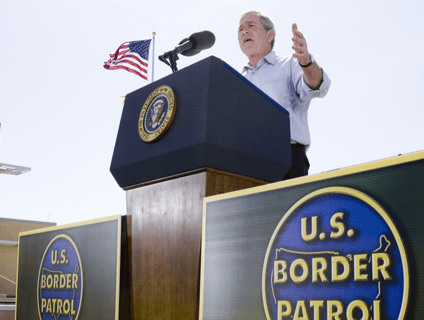

It’s an article of faith on the right that the battle over the guest worker program in 2007 helped doom George W. Bush’s immigration bill, even though a grassroots rebellion over legalization is the more likely factor. Republicans and their allies in business have often argued that immigration reform without a guest worker program cannot pass Congress. But Republicans also fear that reform will hand Democrats millions of new voters, and it’s unclear whether big business, which wants a guest worker program, can convince skeptical GOPers to back a deal. “Do I think business actually delivers votes in Congress based on this?” says a longtime labor activist who lobbied on behalf of the 2007 bill. “I think that’s very abstract and theoretical.”

Businesses want cheap workers, and unions need new members. But they have argued for decades about how best to bring immigrant workers into the United States legally, with few clear answers and several shameful experiments. Past guest worker solutions, such as the mid-century Bracero program—which brought in Mexican agricultural workers to labor under abysmal conditions and for exploitative wages—remain powerful symbols of how such efforts can go horribly wrong. Still, both sides agree the current laws aren’t working.

“The current guest worker program is just as broken as the current immigration system,” says Eliseo Medina, treasurer for the Service Employees International Union, whose father and brother were brought to the US from Mexico to labor in American fields. “I have a first-hand familial experience with how these programs don’t work. They’re abusive and exploitative, that’s why I think from that experience, we need to do something different.”

The problem is in the nature of the concept: Guest workers often don’t want to be “guests”; they want to live and work here, and often overstay their visas. Employers can easily use guest workers’ immigration status to exploit them, and their visas are often tied to their employer, so they can’t simply seek work elsewhere. Nevertheless, there are jobs Americans don’t really want to do, and they end up being filled by immigrants one way or another.

That’s how Diaz and Uvalle ended up peeling crawfish in the cramped room in Breaux Bridge, Louisiana. Crawfish are small, and repeating the same motion for 15 or 16 hours makes workers’ fingers, arms, and hands ache. Workers would occasionally cut their hands while peeling and get infected by a fungus that crawfish sometimes carry. If the guest workers wanted gloves, they had to buy them from a vendor who came by the trailers to sell them odds and ends.

Diaz and Uvalle put up with the tough hours, austere conditions, and broken promises because they needed the money, they said through an interpreter. But beginning sometime in 2009, the work became unbearable. CJ’s Seafood had won a contract with Walmart, and the hours started getting longer. Instead of starting at 5 a.m., they’d start at 4, and then 3, until eventually the guest workers were shuffling out of their trailers at 2 a.m. to unload, peel, boil, and pack the crawfish so they could be shipped out. Instead of stopping at 3 p.m. like they used to, they’d work until 5. Some of the workers, Diaz and Uvalle said, would work for 24 hours or more, all without overtime pay. The trailers themselves had been modified with bunk beds to fit more people. The few American workers at CJ’s Seafood had more freedom—they didn’t have to live in the trailers, and they were allowed to take longer breaks and leave to do things like pick up their children from school. According to Diaz and Uvalle, management started pitting the workers against each other, berating those who didn’t peel fast enough.

One morning in May 2012, just as the shift was starting, Mike LeBlanc, the manager, pulled the guest workers into a meeting and told the few American workers to stay outside. They weren’t working hard enough, he said, and they needed to pick up the pace. If they weren’t happy with the conditions, he said, they could go back to Mexico—after all, there were always more workers there to be found.

But LeBlanc didn’t stop there, according to Diaz and Uvalle. They say LeBlanc told the workers that they could be friends, but that they didn’t want him as an enemy, because he knew good people and bad people—and he knew where all of the workers’ families lived. Doris, LeBlanc’s wife, was translating into Spanish; after LeBlanc finished talking, Uvalle says, Doris angrily added, “You get it? You understand?”

Shortly after that meeting, an alarmed Diaz and Uvalle decided to contact Jacob Horwitz, an organizer with the National Guestworker Alliance (NGA), an advocacy group for foreign workers. They had been in touch with Horwitz since March, having been given his number a year earlier by the vendor who occasionally sold goods at the trailers. For months, Diaz and Uvalle had been quietly sneaking out of the camp at night to meet secretly with Horwitz in parking lots and hotel rooms, telling their supervisors they were going shopping at Walmart.

According to Horwitz, LeBlanc’s threat “made it really clear that this was a forced-labor situation.” Diaz and Uvalle decided to try to organize a strike to force LeBlanc and CJ’s Seafood to allow them decent hours and pay them what they were owed.

They didn’t find many takers. Of the approximately 40 guest workers at CJ’s Seafood, only 8 wanted in, 3 of whom were Uvalle’s relatives—an aunt, an uncle, and a nephew. Several workers told Diaz that they were afraid to be sent back to Mexico; others said they should be grateful to LeBlanc for having jobs at all.

Diaz and Uvalle went ahead with the strike anyway, refusing to work until LeBlanc withdrew what he said at the meeting, agreed to regular hours, overtime pay, and more breaks. They also contacted the Department of Labor. LeBlanc rejected their demands and told them to pick up their last paycheck in the morning. When Diaz and Uvalle showed up, LeBlanc had series of papers for them to sign. He told the striking workers he had already called the police—Diaz and Uvalle said that they understood if they signed the papers they’d have no legal status, and they’d simply be deported. LeBlanc told them to grab their belongings and get off his property within twenty minutes.

Diaz and Uvalle left, but they weren’t done. Over the next few weeks they met with other workers on the Walmart supply chain and staged a series of protests with the NGA, one at the Walmart in New Orleans and another at the home of Michelle Burns, a prominent Democrat and Walmart executive. The strike garnered some press, enough to force Walmart to respond. A couple of days after the strike, the company told the Daily Beast, “Following our investigation, as well as investigations by the Department of Labor and OSHA, at this time we are unable to substantiate claims of forced labor or human trafficking at CJ’s Seafood.” Mother Jones was hung up on twice when it tried to contact CJ’s Seafood for comment.

Walmart dropped CJ’s Seafood as a supplier in late June, just three weeks after the strike. What the Walmart spokesman had told the Daily Beast wasn’t true—the Department of Labor investigation wasn’t finished. When the investigation concluded in late July 2012, more than a month after the strike, CJ’s was fined more than $34,000 for safety violations and ordered to pay $214,000 for violations of wage and hour rules—including $76,000 in back pay to its workers. Diaz and Uvalle had made CJ’s pay for treating them poorly, but they hadn’t managed to force the company to treat its other workers any better.

Diaz and Uvalle didn’t return to work at CJ’s. As witnesses to labor abuse they were able to acquire U visas, which are granted to immigrants who cooperate with law enforcement investigations. But their experience illustrates how under the current program, guest workers’ tenuous legal status means they have little if any leverage over their employers, who can simply hire more, less-troublesome foreign workers and send the others home.

The bipartisan Senate Gang of Eight thinks they’ve solved that problem. Crafted with the input of business and labor, their plan introduces a new visa program for nonagricultural workers called the W visa, which, unlike the current H-2B visa, won’t tie the workers to a single employer and will allow them to eventually apply for citizenship. That’s supposed to prevent employers from taking advantage of workers: If workers don’t like one job, they could apply for another similar one. But W visa workers would have to find a job quickly—within two months—or risk losing their status.

Business also has agreed to a program that starts at 20,000 W visas and can grow to a maximum of 200,000 based on a statistical formula (PDF) and a panel that oversees the program, something labor wanted to prevent foreign workers from getting too much of an advantage over American ones. The number of visas available every year will be based on recommendations from a new body known as the Bureau of Immigration and Labor Market Research.

Some on the business side, however, think the cap on the number of W visas is a nonstarter. “Between 2003 and 2009, more than 350,000 people came, and in some years more than 600,000 people came illegally to work because we needed them to work,” says Jacoby, who was one of the negotiators on behalf of big business. “How can 20,000 [W visas] accommodate that flow?”

While the W visa undoubtedly has more protections for foreign workers than the H-2B visa, it won’t be replacing it. Up to 66,000 H-2B workers will be allowed in every year. Returning guest workers will be exempt from the cap for at least five years. That means, at least at first, the H-2B program—under which Diaz and Uvalle say they were exploited for years by an abusive employer—will be far larger than the new program that gives workers more protections. While legislators expect the W visa will appeal to employers who want more skilled workers and don’t want to retrain new ones, there’s nothing in the bill itself that keeps employers from choosing the H-2B instead of the W visa. The bill improves the way wages are set in the H-2B program, and like W visa workers, H-2B workers will be able to accrue points toward a green card under the new bill. The temporary nature of the H-2B program makes their path to citizenship a longer, more winding road.

Jennifer Rosenbaum, legal director at the National Guestworker Alliance, says that since the bill would legalize 11 million undocumented immigrants, she doesn’t see the need for a guest worker program. “It doesn’t make any sense except that they want a captive workforce—they don’t just want workers,” Rosenbaum says.

Any foreign-worker program will have to meet demand while protecting the rights of workers, and it won’t be easy for any program to do either, let alone both. In February 2013, while business and labor were hammering out their compromise, Diaz and Uvalle traveled to Arkansas to meet with Walmart executives, who assured them they were taking action to ensure their suppliers were meeting Walmart labor standards, particularly with regard to forced labor.

Kory Lundberg, a spokesperson for Walmart, told Mother Jones that the company has developed an audit system in which a third party will evaluate whether Walmart suppliers are meeting their labor standards. Lundberg wouldn’t say that it was in response to the events at CJ’s Seafood, but he acknowledged that Walmart began developing the audit program after the strike and investigation. “It’s important to us that all the workers in our supply chain are treated with dignity and respect,” Lundberg said.

In the February meeting Diaz and Uvalle say Walmart refused to put any kind of agreement in writing with the guest workers employed by their contractors. Both of them say they don’t trust Walmart to police itself, and that they think other workers on the Walmart supply chain will still be subject to similar abuse.

Since the strike, Diaz and Uvalle, longtime friends, have pursued different paths. They have both remained a part of the NGA’s campaign on behalf of workers on the Walmart supply chain, but after working as a domestic worker, cleaning homes, and taking care of children, Uvalle has decided to leave Louisiana for Texas. Diaz is working as a supervisor at a plant that supplies eggs to supermarkets.

She still doesn’t get paid overtime.