Photos provided by a government scientist show the site of an oil spill in Cold Lake, Alberta.<a href="http://www.thestar.com/news/canada/2013/07/19/nobody_understands_ongoing_spills_at_alberta_oilsands_operation.html">The Toronto Star

Nine weeks ago, an oil leak started at a tar sands extraction operation in Cold Lake, Alberta, and it’s showing no signs of stopping.

On Friday, the Toronto Star reported that an anonymous government scientist who had been to the spill site—which is operated by Canadian Natural Resources Ltd.—warned that the leak wasn’t going away. “Everybody [at the company and in government] is freaking out about this,” the scientist told the Star. “We don’t understand what happened. Nobody really understands how to stop it from leaking, or if they do they haven’t put the measures into place.” The Star reported that 26,000 barrels of watery tar have been removed from the site.

The impacted area spans some 30 acres of swampy forest, said Bob Curran, a spokesperson for the Alberta Energy Regulator (AER), which oversees these sites. According to the Star, pictures and the documents provided by the scientist show that dozens of animals, including loons and beavers, have been killed, and some 60,000 pounds of contaminated vegetation have been removed. (You can see the pictures at the Star‘s website.)

Curran confirmed to Mother Jones that the leak was ongoing as of Tuesday afternoon and said AER was working with the company on a plan to contain the damage. He added that he couldn’t make a firm assessment of what caused the leak until after AER had completed its investigation. “We don’t get into probable causes,” he explained. But he did say that AER was concerned, adding that the leak was “very uncommon—which is why we’ve responded the way we have.”

In response to specific questions about the spill, the company sent Mother Jones a previously prepared statement: “The areas have been secured and the emulsion is being managed with clean up, recovery and reclamation activities well underway. The presence of emulsion on the surface does not pose a health or human safety risk. The sites are located in a remote area which has restricted access to the public. The emulsion is being effectively cleaned up with manageable environmental impact. Canadian Natural has existing groundwater monitoring in place and we are undertaking aquatic and sediment sampling to monitor and mitigate any potential impacts. As part of our wildlife mitigation program, wildlife deterrents have been deployed in the area to protect wildlife…We are investigating the likely cause of the occurrence, which we believe to be mechanical.”

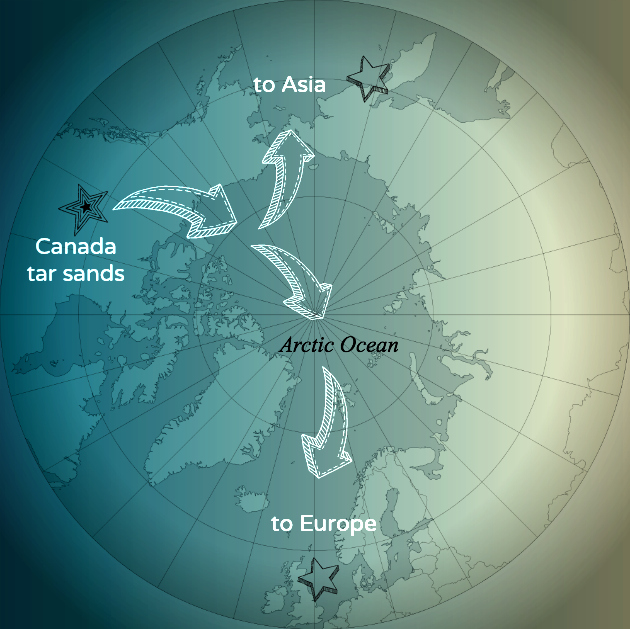

The Primrose bitumen emulsion site, where the leak occurred, sits about halfway up Alberta’s eastern border and pulls about 100,000 barrels of bitumen—a thick, heavy tar that can be refined into petroleum—out of the ground every day. But unlike the tar sand mines that have scarred the landscape of northern Alberta and added fuel to the Keystone XL controversy, the Primrose site injects millions of gallons of pressurized steam hundreds of feet into the ground to heat and loosen the heavy, viscous tar, and then pumps it out, using a process called cyclic steam stimulation (CSS). Eighty percent of the bitumen that can currently be extracted is only accessible through steam extraction. (CSS is one of a few methods of steam extraction.) Although steam extraction has been touted as more environmentally friendly, it has also been shown to release more CO2 than its savage-looking cousin.

There have been accidents before with steam injection mining. At another kind of steam injection site, the high pressure at which the steam is injected exceeded what the terrain could bear and blasted wild-looking craters, hundreds of feet wide, into the landscape.

Curran said that although the current leak is extremely unusual, a similar—but smaller—incident occurred at Primrose back in 2009. In that case, tar started bubbled out of “thin fissures” in the ground near the wellhead. According to a report from the Energy Resources Conservation Board—an oversight agency that was folded into AER last year—new limits on steam pressure were imposed, and extraction was allowed to resume.

But on May 21, something new went wrong at the Primrose site. According to Curran, springs of watery bitumen started popping up, seeping out of the earth. When the first three appeared, AER shut down nearby steam injection. When a fourth appeared in a body of water close by, AER shut down all injection within a kilometer of the leaks, and curtailed adjacent steaming operations. “The first three are just leaking right there at the surface,” Curran says. “Small cracks in the ground, just kind of bubbling out.”

It’s unclear what long-term consequences might result from the spill. “They don’t know where this emulsion has gone, whether it has impacted groundwater,” says Chris Severson-Baker, managing director of the Pembina Institute, a nonprofit group that studies the impacts of tar sand mining. According to Severson-Baker, the question is what will happen if the geology at Primrose is to blame. “[If] the problem is inherent to the project itself, are they going to remove the permits for the project?” Even so, he claims the damage might already be done. “At this point, what can actually be done to prevent the impact from continuing to occur? I don’t think there is anything that can be done.”