Rep. Ruben Hinojosa (D-Texas).<a href="http://www.flickr.com/photos/34120602@N05/3312205772/in/photolist-63FVo5-77rzYM-bUxuMK-dkohvw-dsivCC-dkBBmV-epzEma-epzEi4-7PBrKg-epzE8X-fbFkiy-9uGnes-9pnPR7-9gW8nt-9d6ScP-9d9YBf-9d9YN9-9gZfBJ-9d6TqT-bUxuK4-aRqTvT-aRqThP-aRqTbR-aRqVvK-dsivBj-dsivzd">House Committee on Education and the Workforce Democrats</a>/Flickr

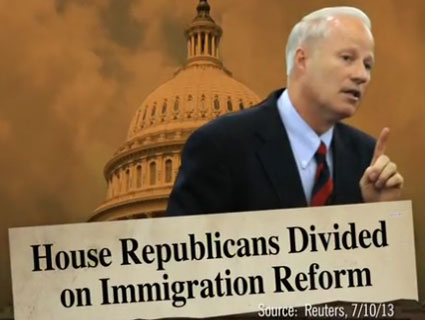

Immigration reform advocates representing border communities continued to press for a more humane approach to security measures on Wednesday outside the US Capitol. Texas Democratic Reps. Ruben Hinojosa and Beto O’Rourke, who both represent border districts, joined them to tout Rep. Mike McCaul’s (R-Texas) bipartisan Border Security Results Act as an alternative to the Senate immigration bill’s $40 billion Corker-Hoeven compromise, which O’Rourke denounced as a “bonanza” for defense contractors. McCaul’s bill emphasizes the more efficient use of existing resources, but it is just one of several enforcement bills advanced by House Republicans.

Hinojosa and O’Rourke spoke alongside human rights advocates, a sheriff’s chief deputy, and families of relatives who have gone missing along the US-Mexico border. Christine Kovic, an associate professor of anthropology at the University of Houston-Clear Lake, distributed a report she authored that explained how, even with border crossings at a 40-year low, deaths are on the rise as increasingly tough enforcement policies force immigrants to cross in more isolated areas. Meanwhile, record deportations continue to separate undocumented parents from their children who have legal status.

O’Rourke agreed. “We will definitely see more death and suffering if we pass immigration reform with something like Corker-Hoeven,” he said. “I’m here to tell you that I support immigration reform, but we have to do it in a reasonable, moral, humane, and fiscally responsible manner. This is one area where I think the House is going to get this one right.” El Paso, where O’Rourke is from, reinforces his views well: Last year, it boasted the lowest crime rate in the country among large cities despite its close proximity to Juarez, Mexico, a town plagued by drug cartel violence.

McCaul’s bill calls on the Department of Homeland Security to devise a strategy for securing land and sea ports of entry that includes implementing biometric tracking systems and measuring the success of turning back illegal border crossers and seizing trafficked drugs. Each year, DHS would have to submit a report to Congress laying out a resource allocation model focused on the border’s most porous regions.

The bill, which is co-sponsored by a bipartisan group of 20 House members (but not Hinojosa or O’Rourke), isn’t on its own likely to appease Republicans who want guarantees that the border would be tightly enforced before considering legal status for any of the country’s 11 million undocumented immigrants. The Federation for American Immigration Reform, an anti-immigration group, has dismissed the bill as too vague and similar to the Senate “amnesty bill,” with no guarantees that its metrics would be enforced before undocumented immigrants are granted legal status if the House turns the corner on citizenship measures.

Benny Martinez, chief deputy of the Brooks County sheriff’s department in Texas, fears that immigrants who die crossing the border will continue to be treated as “collateral damage” in Congress border security negotiations. “We cannot actually criminalize all [undocumented border crossers] as a whole, and I think that is what’s happening here” in the immigration debate, Martinez says. “What that does is puts distance between ‘you’ and ‘them.’ So you really don’t pay attention to the issues.”

Immigration reform groups have mixed feelings about the House’s plans for border security. Arturo Carmona, executive director of Presente.org, says that his organization is still reviewing McCaul’s bill but that other enforcement bills passing out of House committees “paint a pretty dark picture for the Latino community.” He points to the SAFE Act, which would pressure undocumented immigrants to self-deport and defer DHS’s authority to state and local governments, which often have abysmal records of treating immigrants humanely.

“I do think the House Republicans’ antipathy to the Senate bill will help us in conference with respect to the Senate border provisions,” says Frank Sharry, executive director of America’s Voice. But for Sharry, it’s a waiting game. The bipartisan Gang of Seven plans to release its long-delayed reform bill in September after the month-long August recess. Then, Republicans will have to decide whether to support a concrete, comprehensive proposal. “That,” Sharry says, “will be game on.”

In early August, McCaul plans to lead a congressional delegation on a tour of the southern border, beginning in San Diego. Hinojosa plans to join him when he reaches southern Texas’s Rio Grande Valley. “We’re going to show them just how much we have already invested in more than tripling the number of border patrolmen that we had 16 years ago when I came to Congress,” Hinojosa said. “We’re going to show them the improvements on what has already been done in the bill that was passed under George Bush to build the wall and fence. All of this has improved national security.”

Meanwhile, immigrants whose families have been harmed by the system just want answers. Luis Fuentes, a native of El Salvador who lives in Long Island on a temporary protected status permit, hopes to finds his missing wife. She disappeared along the border last September with her sister, who was abducted and raped repeatedly for more than two days in Alamo, Texas, before escaping. Carina Estrada, a permanent resident from Guatemala City who lives in DC, wants Border Patrol officials to confirm whether a body found in May in the Rio Grande is her sister. DNA testing is required by Texas law but is poorly coordinated, and often, Martinez says, a body is only identified by a physical description like a tattoo.

“It’s very difficult waking up every day, and my kids say, ‘Where’s my mom?'” Fuentes says. “It’s very difficult to answer that question.”