Income inequality in America is has spiked in the past three decades, and has only worsened since the recession. But that’s not the only factor contributing to the deepening divide between the rich and poor. Recent research has shown that Americans enjoy less social mobility than people in other industrialized countries—in other words, American kids are less likely than foreign kids to grow up to make more money than their parents. A new study by a team of economists at Harvard and University of California–Berkeley provides the most detailed look yet at patterns of upward mobility in the US, shedding light on why it’s not so easy to pull yourself up by your bootstraps in the US of A.

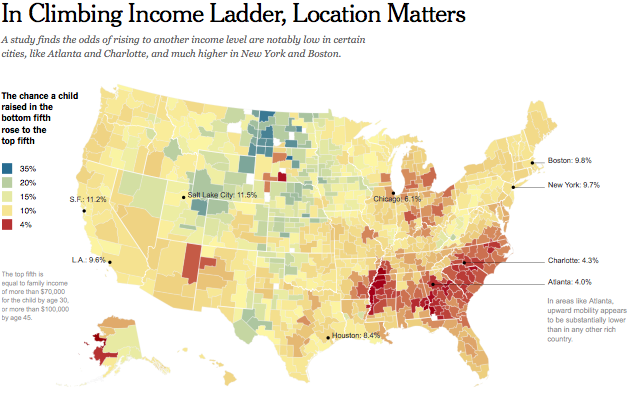

The study’s findings, which were first reported in the New York Times on Monday, are based on millions of earnings records. Researchers found that children born into the poorest 20 percent of households are least likely to end up in the top 20 percent of income earners (more than $70,000 by age 30) in the Southeast and the industrial Midwest. Upward mobility is particularly lacking in Memphis, Indianapolis, Atlanta, and Columbus. Poor children are most likely to be able to work their way to an upper-income life in the Northeast, Great Plains and the West, including in cites such as New York, Boston, Salt Lake City, Pittsburgh, and Seattle. Here’s what that looks like, via the Times:

The researchers were surprised that what most contributed to social mobility wasn’t heftier tax breaks for the poor or a stronger safety net. The difference between high-mobility and low-mobility communities has more to do with early education, family structure, and the physical geography of metropolitan areas. The Times explains:

The researchers concluded that larger tax credits for the poor and higher taxes on the affluent seemed to improve income mobility only slightly. The economists also found only modest or no correlation between mobility and the number of local colleges and their tuition rates or between mobility and the amount of extreme wealth in a region.

But the researchers identified four broad factors that appeared to affect income mobility, including the size and dispersion of the local middle class. All else being equal, upward mobility tended to be higher in metropolitan areas where poor families were more dispersed among mixed-income neighborhoods.

Income mobility was also higher in areas with more two-parent households, better elementary schools and high schools, and more civic engagement, including membership in religious and community groups.

Regions with larger black populations had lower upward-mobility rates. But the researchers’ analysis suggested that this was not primarily because of their race. Both white and black residents of Atlanta have low upward mobility, for instance.

…

The comparison of metropolitan areas allows researchers to consider local factors that previous mobility studies could not—including a region’s geography. And in Atlanta, the most common lament seems to be precisely that concentrated poverty, extensive traffic and a weak public-transit system make it difficult to get to the job opportunities. “When poor communities are segregated,” said Cindia Cameron, an organizer for 9 to 5, a women’s rights group, “everything about life is harder.”

Although location has a lot to do with whether poor kids in Indianapolis or Montgomery will be able to live better than their parents, for rich kids, geography doesn’t really matter. The study found that the chance rich kids will grow up to be rich is pretty much the same across metropolitan areas around the country. Of kids who grew up one-percenters, for example, one out of three will be making at least $100,000 by the time they turn 30.