June 14 letter from 32 House Democrats to the Department of Labor.

A letter that a group of progressive Democrats sent to federal regulators opposing new protections for millions of Americans’ retirement accounts was drafted by a financial-industry lobbyist, according to documents obtained by Mother Jones.

The Department of Labor, which oversees the federal law setting minimum standards for many retirement plans, would like to require retirement investment advisers to act in the best interest of their customers, as opposed to their own best interest.

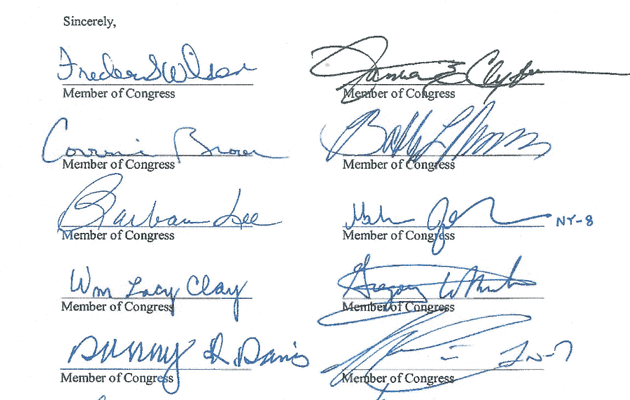

But 28 out of the 43 members of the Congressional Black Caucus (CBC)—a group of African American members of Congress that advocates the interests of low-income people and minorities—signed onto a June 14 letter opposing the rule. So did Democratic lawmakers Pedro Pierluisi of Puerto Rico, Tulsi Gabbard of Hawaii, Ed Pastor of Arizona, and Jim Costa of California.

The letter’s metadata indicates it was drafted by Robert Lewis, a lobbyist who works for the Financial Services Institute (FSI), an investment industry trade group:

Together, the liberal lawmakers who signed the letter have received tens of thousands of dollars in campaign money from the securities and investment industry in recent years.

In the letter, the lawmakers caution the Labor Department against proposing new regulations, warning that a strict new rule on retirement advisers may cause many of them to leave the market and thus “could severely limit access to low-cost investment advice” for “the minority communities we represent.”

But the Department of Labor, financial reform groups, and consumer advocates say the regulation won’t make it any harder for poor and middle-class customers to get investment advice. The current law doesn’t do enough to prevent unscrupulous investment brokers from parking Americans’ hard-earned cash in high-fee investments that benefit themselves, even if it’s not in their customers best interests, argues Barbara Roper, director of investor protection at the Consumer Federation of America.

Current Labor Department regulations governing retirement investment advisers date back to 1974, when most people had traditional pension plans that left few decisions to workers. Today, most employees have to figure out how to invest their retirement money on their own. Each year, according to the Congressional Research Service, about 10 million people change jobs and must move their retirement money from employee-sponsored 401(k) plans into individual retirement accounts. As Americans seek advice on what to do with those IRAs, they often consult advisers who stand to profit by duping investors into making unnecessary high-fee investments.

“This rule is about protecting people from conflicts of interest,” says Phyllis Borzi, the Department of Labor’s assistant secretary for employee benefits security, who is spearheading the push for a stronger investment adviser rule. “Those conflicts harm everyone who is doing the right thing and trying to save.”

Borzi emphasizes that an updated adviser rule is especially important to protect working-class people from predatory investment counselors. Conflicts of interest in the business “are particularly harmful when you’re talking about low-income workers, who can least afford to lose their hard-earned savings,” she says.

But the industry has a lot to lose from a rule change. FSI has expressed concern that the regulation would limit the types of fees advisers can collect for servicing retirement accounts. The trade group spent $196,000 on lobbying in the just the first quarter of 2013—that’s nearly half the the total it spent on lobbying in all of 2012. On a recent federal disclosure form, FSI listed the Labor Department’s investment adviser rule at the top of its lobbying issues. FSI did not respond to requests for comment on the ghostwritten letter.

It’s not unheard of for lobbyists to ghostwrite letters—or even legislation—for lawmakers. In May, Mother Jones reported on a House bill written almost entirely by a Citigroup lobbyist that would vastly expand the types of risky trades a bank can conduct with taxpayer-backed money.

The House Dems’ letter of opposition could help the financial industry make a case that there is widespread concern about the change. The signatories represent low- and middle-income districts with large proportions of minority voters. The CBC has long backed progressive policies that help low-income folks, such as nutrition assistance, jobs programs, and unemployment benefits. Fifteen of the CBC members who signed the letter are also part of the 68-member Congressional Progressive Caucus.

A spokeswoman for the CBC emphasized that the caucus is concerned about the effect of the rule on the “smaller, independent financial services firms that provide tailored financial services to underrepresented communities” that FSI represents, adding that “the one-size-fits-all approach to policymaking is not always in the best interest of our constituents.” (The offices of the non-CBC signatories did not respond to a request for comment.)

Marcus Stanley, policy director at the advocacy group Americans for Financial Reform, notes that no matter the size of the firms FSI represents, the trade group has “a very clear interest that gives them a perspective on this that can be at odds with the perspective of constituents who are investing their retirement investments.”

In just the last election cycle, lawmakers who signed the June 14 letter raked in over $88,000 in donations from the securities and investment industry, according to the Center for Responsive Politics. In this case, says Bart Naylor, a financial policy advocate at Public Citizen, “serving ones’ own self interest is manifest abidingly, conspicuously, and outrageously.”

The proposed investment adviser rule is under attack on other fronts. A Republican-sponsored bill that would weaken the Department of Labor’s power to write rules on retirement investments is expected to hit the House floor this fall. And just last week, 10 Senate Democrats wrote a letter to the administration urging the department to hold off on its proposal.