Sealand<a href="http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Sealand.jpg">Ryan Lackey/Wikimedia Commons

A few months ago, internet entrepreneur Avi Freedman received an unexpected email from a prince. A decade earlier, Freedman had been part of an effort to create a data haven—a safe place where information could be stashed far from the reach of prying eyes and nosy governments—on the world’s smallest and most notorious micronation, Sealand, a 120-by-50-foot anti-aircraft platform seven miles off the British coast and 60 feet above the waters of the cold North Sea. Now Freedman’s ex-partners, the self-proclaimed royal family of Sealand, wanted to try again.

Freedman said yes. HavenCo, the Sealand-based data haven that failed spectacularly a decade ago, relaunched this weekend. And this time, Freedman thinks it’s going to work. HavenCo is offering customers total control over how secure their data is—and if used correctly, its technology could help internet users who want to avoid the National Security Agency’s sweeping data dragnet.

To understand what HavenCo is trying now, it helps to understand how this all started. HavenCo’s first iteration was intended as a kind of techno-utopia where the revolutionary potential of the internet could be protected. It was supposed to be a self-contained, hypersecure data fortress, with servers located on site in the middle of the North Sea. The company promised it would destroy its servers rather than ever reveal its clients’ data. But like many dot-com-era schemes, its founders’ fantastical vision overshot what the market, and their own capabilities, could bear.

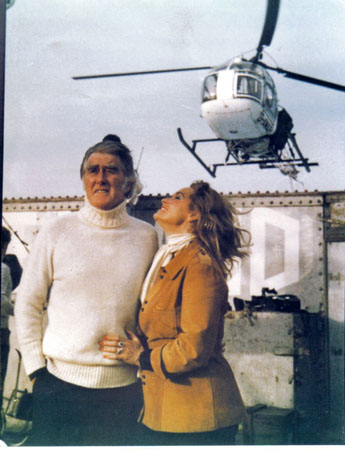

The Principality of Sealand, where HavenCo was once based, was founded in 1967 by a waggish former British Army Major named Roy Bates. Bates, who had launched Radio Essex, an unlicensed “pirate” radio station, after leaving the Army, took over the rusting World War II-era anti-aircraft platform that became Sealand after the British government had shut down his previous base, another anti-aircraft platform closer to the British shore. On Christmas Day 1966, Bates evicted the staff of a rival pirate radio station, Radio Caroline, from the platform. When the Radio Caroline broadcasters tried to retake it, Bates defended his prize with an air rifle, homemade bombs, and a good bit of skullduggery. But it wasn’t until the summer of 1967 that his wife, Joan, made a crack about wanting “a flag with some palm trees” to go with her “island” that the couple found a “dereliction of sovereignty” loophole in international law that they believe allowed them to take over what Britain had neglected and proclaim Sealand its own sovereign nation.

The Bateses furnished their tiny kingdom with all the trappings of nationhood—minting currency, sewing a flag, issuing stamps and passports (at one point suffering a scandal when forgeries popped up in an international smuggling ring), and topping it off with a national anthem and elaborate titles for them and their friends. There was even a coup by the Minister of Foreign Affairs, Alexander Achenbach, who had Prince Michael Bates, Roy’s son, taken hostage. The Bates retook their country in a dawn helicopter raid with the help of a James Bond stunt pilot. Achenbach later set up a Sealand government-in-exile (complete with a website), which, according to Ars Technica, “dabbles in perpetual motion machines, UFOs, conspiracy theories, and revisionist history.” The Brits also considered ousting the Bates, but Roy played the press expertly, offering them madcap stories. Headlines of Marines being readied to storm Sealand and the Ministry of Defense falling for Roy’s double agent proved that it was better to leave the Bates alone than continue looking foolish.

Over the next three-plus decades, Sealand was approached with various outlandish schemes involving smuggling, tax havens, a “pleasure island,” and even an outpost for disgruntled Argentines during the Falklands War. In the mid-1990s, a Spanish businessman claiming to be Sealand’s “prime minister” began soliciting investors for a project to expand the platform and build a “luxury hotel and casino, business center, sports complex, medical center, tuition-free University of Sealand, and Roman Catholic cathedral.”

It looked like Sealand had finally found the perfect match for its maverick, give-’em-hell spirit when it paired up with Ryan Lackey and Sean Hastings. Lackey was a 21-year-old cryptography wiz who had recently dropped out of MIT to work on an electronic-payment startup that he had cofounded. With a round face and shaved head, often donning all black in pictures, he looked every bit the part of hacker rebel. Hastings, 32, was also a dropout. In 1989, he left the University of Michigan without a degree because he didn’t want to fulfill his humanities requirement, and had since made a living playing poker and working as a programmer. After a job with an offshore-betting company fell apart, Hastings moved to the island of Anguilla, where he started a company called IsleByte, to operate as a data haven—like a tax haven, but for information, allowing pornographers, gamblers, and copyright pirates to operate beyond the reach of local laws banning their businesses.

When Hastings and Lackey met at a financial-cryptography conference on the island in 1998, they discovered they were kindred spirits. They both belonged to a class of techno-libertarians called “cypherpunks,” who believed encryption and technology were the key to fighting government overreach. Not long after the cryptography conference, Hastings ditched island life and headed back to the United States, where he and Lackey started to brainstorm. Anguilla might have been good for offshore companies, but Hastings had found it a poor fit for his data haven project—porn and gambling were both heavily restricted and could get the site shut down. If Hastings and Lackey wanted to create a real data haven, they decided they need to find a more permissive base of operations. Once they were both back in the States, the pair began looking for a lax, welcoming government. They scoped out Pacific islands and even considering building their own on the Cortez Bank, 100 miles of the coast of San Diego, or mooring a tanker off the coast of LA. But when they read about Sealand and its authority-flouting, pirate radio past in Erwin Strauss’s How to Start Your Own Country, they knew they’d found what they were looking for. The Royal Family of Sealand, it seemed, was a bunch of bomb-throwing mavericks, just like them.

To entice the Bateses, Hastings pitched the project as “pirate internet.” Using Sealand as its base, HavenCo was going to offer unprecedented protection for its clients’ information. All hosting would be done on secure servers jammed into the legs that support Sealand’s deck. The servers would live in an atmosphere of pure nitrogen, so you’d need scuba gear to access them, and they’d be connected to triple-redundant generators and three independent internet links. To cement the Bondian flare of their plans, the platform would have armed guards manning .50-caliber machine guns, as well as magnetic mines to fend off gunboats, self-destruct devices in the servers, and a general “bugger off” attitude to anyone who wanted to come snooping. If they were ever forced at gunpoint to hand a server over, Lackey told Wired, “We’d power off the machine, optionally destroy it, possibly turn over the smoking wreck to the attacker, and securely and anonymously refund payment to the owner of the server.”

The company would cater to people who, for one reason or another, wanted to operate without the hindrance of laws. Hastings and Lackey envisioned a client list that ranged from the exiled Tibetan government to pyramid schemes, and online gambling sites to companies sending porn into Saudi Arabia, providing, as James Grimmelmann, the law professor who penned the definitive legal history of HavenCo, wrote, “a combination of first-world infrastructure and third-world regulation.” It was a place where just about anything you wanted to do was fair game. It had a few key rules, written according to its own code of ethics: child porn traffickers, drug-money launderers, spammers, corporate saboteurs, and anything else that could jeopardize its access to the net were all persona non grata.

The revolutionary vision behind HavenCo caught the eyes of the heavyweights of the tech world (including a glowing 7,000 word profile in Wired) and the pair eventually scraped together a reported $1 million seed fund. A serious chunk of the money came from two big-deal backers: Joi Ito, now the Director of MIT’s Media Lab, and Avi Freedman. “I think it’s a great project and I hope to see it test some of the edges of our geopolitical economy,” Ito told Wired just before HavenCo’s initial launch. Freedman also thought HavenCo could become a powerful political catalyst. “I have a firm belief that countries that encourage and foster open communication will prosper. Those that don’t, won’t,” he told Wired. “I see the establishment of a company to focus on the data haven aspect as an important first step. There is idealism involved. This is not strictly economic.” But money was a consideration—and the founders of HavenCo talked big. “Five years from now,” Lackey told Wired, “we are either going to be completely broke or we’re going to be fantastically wealthy.” One of the backers estimated that HavenCo would be pulling in $50 to $100 million in profits by the end of its third year.

The hype might have done more harm than good. HavenCo struggled to get up and running. “Almost all time was spent dealing with press,” Lackey said in a presentation at the tech conference Defcon in 2003. “No one took responsibility for sales, and there was no ticketing system, so basically all initial inquiries were lost or mishandled.”

It wasn’t just that the business was disorganized—HavenCo struggled to put together the kind of high-tech data fortress that the Wired profile had promised. The sparkling, secured server rooms never came close to what the public statements depicted. “The real reason visitors weren’t allowed down the south tower [where the servers were kept],” writes Grimmelmann, “wasn’t because they might see or damage something they shouldn’t, but rather because there was nothing to see.” HavenCo’s headline grabbing advantage—its improbable location—also turned out to be one of its biggest stumbling blocks. There’s a reason you don’t see many data centers on sea platforms—Sealand, Grimmelman noted, had “an absurdly inefficient cost structure. Every single piece of equipment, drop of fuel, and scrap of food had to be brought in by boat or helicopter.”

To make things worse, the dot-com bubble burst, and the company that had provided HavenCo’s fiber-optic link to the rest of the world went bust. The data haven site became a target for denial of service attacks. Then, for reasons he never made public, Hastings abandoned ship in early 2000, leaving Lackey pulling long shifts on the platform. Lackey’s relationship with the royal family of Sealand began to fray. He became more secretive, they claimed, starting projects without telling anyone, chaffing at the way the family did business and nosed into his technical decisions. He “became doctor evil in his lair,” Roy’s son Michael told Ars Technica in 2012.

When the royal family nixed a plan to host a site that would illegally rebroadcast DVDs to its users—exactly the sort of shady project that HavenCo had been built for—things finally broke down. Despite Sealand’s wild history, the Bateses were wary of antagonizing the British and upsetting their delicately balanced claim to sovereignty. They worried that the deal could compromise their relationship with the United Kingdom, and refused to host the DVD site. Lackey was done. In May 2002, he took a deal from the royal family to be repaid the $220,000 he had put into HavenCo and hit the bricks. HavenCo announced that Lackey wasn’t employed there anymore, took his computer, and locked him out. According to Lackey, Sealand had “nationalized” HavenCo.

After that, HavenCo just kind of faded away. The dreams of nitrogen-flooded rooms, armed guards, and glittering rows of secure servers never worked out. HavenCo’s website finally went dead in 2008, and the company was no more.

In the intervening years, though, Freedman stayed in touch with the Bateses, meeting them for dinner in London or catching up with them on family trips to Las Vegas and Los Angeles. The idea of a new HavenCo first came up in London in the summer of 2010, when he was talking with Prince James Bates, Roy’s grandson, about the e-commerce site James had launched to peddle Sealand gear. For the next two and a half years, the idea floated in limbo. By this January, when Prince James sent Freedman a three-line missive about the idea, things had changed. Freedman had noticed the trend of hosting companies offering beefed-up security, and was mulling how he could do better. He said yes.

HavenCo 2.0, like its predecessor, still aims to help users “control the tradeoffs between privacy and security on the one end and convenience and ease of use on the other,” Freedman says. But Freedman and the Bates have accepted that “a crypto-utopia is never going to be adopted by the masses,” Freedman says. If the first HavenCo was built for security purists, the mission of HavenCo 2.0 is to bring the best tools of the tech world to a wider audience, and let people control their own security. The idea is to give people the tools to send and store stuff with as many levels of security as is practically feasible, and then let them decide how paranoid they want to be. “Sealand has always prided itself on freedom,” says Prince James Bates, Roy Bates’ grandson. “New laws around the world remove so much of an individual’s right to freedom and privacy that we want to give that back. It’s not about protecting criminals, it’s about helping law abiding citizens to avoid this unregulated drag net surveillance.”

This time, Freedman decided to focus on building an ultrasecure communication and storage system that bundled existing technological tools. HavenCo 2.0 has four main components: virtual private networks (VPN), which create private networks over public ones; secure network storage; Least-Authority File System (LAFS) storage, an open-source, decentralized storage system; and web proxying, which allows users to shield their IP address by routing through other servers. The end goal is creating communications and storage that are key-encrypted from start to finish.

A way to stay out of the NSA dragnet might be the biggest draw, and the combination of proxies, VPNs, and encryption that HavenCo has packaged could help protect users’ data from the kind of wide-scale surveillance that has recently come to light. The NSA revelations “have turned [data security] into a market that is needed by everyone using the internet and not just the select few that previously understood the need for privacy,” says Prince James. “The revelations about the NSA coming out confirmed what a lot people expected,” adds Freedman, “but it didn’t change what we’re doing.”

Sealand still plays a role in HavenCo’s new business plan, but this time, Freedman says, HavenCo 2.0’s servers are going to be based in the United States and the European Union, not stuffed into the legs of an anti-aircraft platform. (Some of the servers are even in northern Virginia, a couple dozen miles from the NSA’s Maryland headquarters.) The company will use the platform to stash cold data (i.e., drives that aren’t connected to the internet and don’t need to be quickly accessible), including encryption keys. Without the encryption keys, the data stored on the mainland servers is all but useless, and Sealand gives HavenCo enough time to shut down their backup servers and dump the keys. “We’re not advertising thermite charges or EMPs,” says Freedman, but “it’s a less exotic method of making the machine a cold dead box.”

It’s not clear whether HavenCo’s 2.0’s backers have fixed all the problems that doomed the first iteration of their quixotic venture. But perhaps it doesn’t matter. Roy Bates, Sealand’s first prince, had a saying about life in his little nation: “We may die rich, we may die poor. But we certainly shall not die of boredom.”