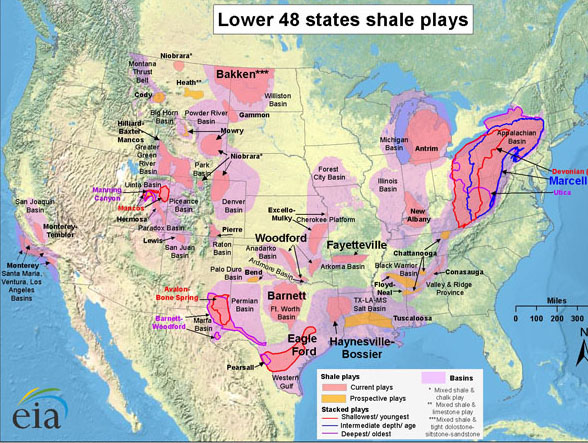

Still trying to figure out what the big deal with fracking is? Hydraulic fracturing—fracking for short—is the controversial process that has fueled the new energy boom in the US, making it possible to tap reserves that had previously been too difficult and expensive to extract. It works by pumping millions of gallons of pressurized water, with sand and a cocktail of chemicals, into rock formations to create tiny cracks and release trapped oil and gas. It’s been tied to earthquakes and has led to a number of lawsuits, including one that resulted in a settlement agreement that barred a seven-year-old from ever talking about it. At the same time, fracking has also created a glut of cheap energy and is helping to push coal, and coal-fired power plants, out of the market.

But for all the fighting about whether fracking is good or bad (and research has shown the more people know, the more polarized they become), many people don’t understand what fracking actually is. The Munich-based design team Kurzgesagt has put together a video that explains why fracking—which has been around since the 1940s—just caught on in the last ten years, and why people are worried. The video, which was posted earlier this month, has gone viral, and racked up over one million views in less than 10 days.

The video gets a lot right, but critics have also taken issue with a few of its claims. For example, the video states that fracking companies “say nothing about the precise composition of the chemical mixture but it is known that there are about 700 chemical agents which can be used in the process.” Energy in Depth, an industry group, has released a response noting that companies do disclose some information about chemicals used in fracking. What that group doesn’t mention, however, is that companies don’t have to disclose chemicals that are designated as “trade secrets,” which is a pretty serious exception.

Energy in Depth also quotes former EPA chief Lisa Jackson’s testimony (among others) that “in no case have we made a definitive determination that the [fracturing] process has caused chemicals to enter groundwater.” The key word here is “definitive”—there is a growing body of evidence that fracking can be linked to increased levels of methane, propane, and ethane in groundwater near fracking sites (likely due to faulty wells), and there are plenty of reasons to question whether pumping billions of gallons of toxic fluid into disposal wells is a good idea. (ProPublica has a couple of great, long pieces on injection wells.)