People have really gotten comfortable not only sharing more information and different kinds, but more openly and with different people. That social norm is just something that has evolved over time. —Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg

If you have something you don’t want anyone to know about, maybe you shouldn’t be doing it in the first place. —Former Google CEO Eric Schmidt

The conventional wisdom in Silicon Valley is that nobody cares about online privacy, except maybe creeps, wingnuts, and old people. Sure, a lot of us might say that we don’t like being tracked and targeted, but few of us actually bother to check the “do not track” option in on our web browsers. Millions of people have never adjusted their Facebook privacy settings. According to a recent Pew survey, only small fractions of internet users have taken steps to avoid being observed by hackers (33 percent), advertisers (28 percent), friends (19 percent), employers (11 percent), or the government (5 percent).

What’s going on here? The short answer is a lot of pretty twisted psychological stuff, which behavioral scientists are only now starting to understand.

Our uneasy relationship with the internet begins with the fact we don’t really know who can see our data and how they might exploit it. “Not even the experts have a full understanding of how personal data is used in an increasingly complicated market,” points out Carnegie Mellon University public policy professor Alessandro Acquisti, who researches the psychology behind online privacy perceptions. Behavioral economists often refer to this problem as information asymmetry: One party in a transaction (Facebook, Twitter, advertisers, the NSA) has better information than the other party (the rest of us).

The upshot is that we can’t agree on what our privacy is worth. A study last year by Acquisti and Jens Grossklags of the University of California-Berkeley found that people were willing to accept wildly varying sums of money in exchange for giving out their email address and information about their hobbies and interests—from $0 to $100,000.

Our struggle to weigh the importance of online privacy reflects a classic case of what economists call “bounded rationality.” That is, the ability to decide things rationally is constrained by a blinkered understanding of how those decisions might affect us.

Because becoming an expert on privacy issues is so time consuming, we tend to fall back on a variety of shorthand ways to make decisions based on our own impressions. One well-documented example is that people tend to conflate security and privacy. They might assume, for instance, that their privacy is protected by merchants that offer encrypted online transactions. Or they may interpret the mere presence of a privacy seal or privacy policy on a website as sign of protection.

Our bounded rationality on privacy matters makes us more vulnerable to all sorts of persuasion tactics aimed at getting us to disclose things. Behold the following behavioral examples of how, even if we really care about online privacy, we’re easily prodded into behaving as though we don’t.

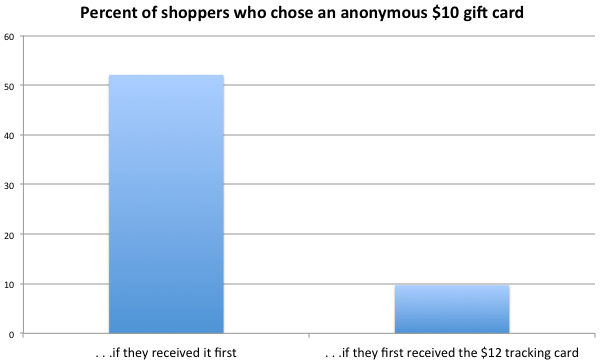

1. Our willingness to sell our privacy is greater than our willingness to pay for it

To test this notion, Alessandro Acquisti’s researchers recently went to a shopping mall, where they offered passersby one of two free gift cards. People were given either a $10 gift card that would allow them to shop anonymously or a $12 gift card that would link their names to their purchases. Next, those who first received the $10 card were asked if they wanted to swap it for the $12 card, effectively selling their privacy for $2. And those who first received the $12 card were asked if they wanted to trade it for the $10 card, effectively buying their privacy for $2. Though the choices were basically equivalent, Acquisti found that shoppers who started with more privacy (the $10 card) valued it much more than those who started with less (the $12 card).

This helps to explain why so many people willingly sell their privacy by, say, signing up for a grocery store rewards card or a free email account, while so few will pay to protect it by, for instance, using anonymity software, which costs time to research, install, and use.

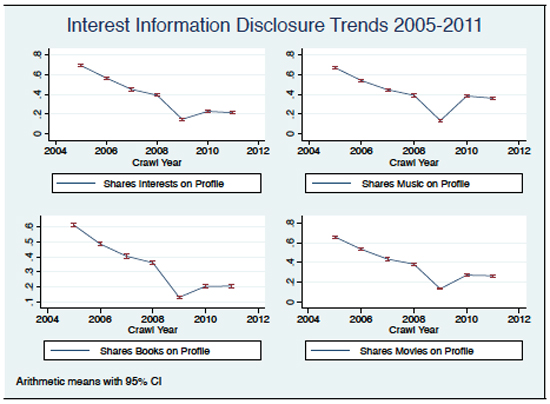

2. We reflexively accept default privacy settings

From 2005 through May 2011, Acquisti’s team tracked the activities of 5,076 Facebook users. Over time, the users gradually decreased the amount of information they shared publicly—until 2009. That’s when Facebook changed its default privacy settings to make profiles more public, but also encouraged users to review their settings and adjust them for more privacy if desired. Look what happened:

3. We’re caught in a Privacy/Control Paradox

In 2011, Carnegie Mellon researchers mimicked what happens on social-media websites by asking students to answer 10 sensitive questions about personal behaviors such as stealing, lying, and taking drugs. The students could decline to answer any of them. One group of students was told in advance that their answers would be automatically published. A second group was asked to check a box if they agreed to give the researchers permission to publish all their answers. And a third group was asked to check a box next to each question to give permission to publish that specific answer—a condition that emulates what happens on blogs and social networks. (See the image at the top of the story.) Though each approach was functionally the same, the third group, the one who was given the most granular control, divulged twice as much sensitive information as the first group. Members of the second group were also significantly more willing to share, even though they knew all of their responses would be public.

These findings strike at the heart of what’s known as the Privacy/Control Paradox: The feeling of control that you gain by checking a permission box before you publish, say, that bong hit photo, actually makes you more willing to share it with strangers than you otherwise would have been. In other words, the mere offer of control over your online privacy may induce you to be more reckless with it.

4. We fall for misdirection

Many social networks give users granular control over how their data is shared among users, but very little control over how it’s used by the services themselves. This is a classic case of misdirection—the magician’s trick of calling attention to one hand while the other stuffs a rabbit inside a hat. A Carnegie Mellon study published in July found that misdirection caused people to disclose slightly more information about themselves than they might otherwise.

5. We’re addicts

Some of the same psychological quirks that cause people to smoke cigarettes also explain why they don’t stop sharing personal details online. In short, we value immediate gratification, discount future costs, believe our own risks are less significant than the risks of others, and have trouble calculating the cumulative effects of thousands of small decisions. People “who genuinely want to protect their privacy might not do so because of psychological distortions well documented in the behavioral economics literature,” Acquisti writes. And “these distortions may affect not only naive individuals but also sophisticated ones.”

6. IGNORANCE is bliss

Ignoring privacy threats and sticking your head in the sand might actually be a good idea. Consider the recent revelation that the NSA targets people who use Tor anonymity software—just because. So why bother to become a privacy expert? Caring too much about privacy, as Google’s Eric Schmidt has implied, might be taken as a sign that you have something to hide.

This “ah, fuck it” approach is known to behavioral economists as rational ignorance. “Even those that are privacy sensitive among us may rationally decide not to protect their privacy,” Acquisti explains. “Not because they don’t care, but because it’s just too hard. You could be trying to do everything right, and your data could still be compromised.”

Maybe that’s why you clicked on this story, but probably still won’t change your Facebook settings.