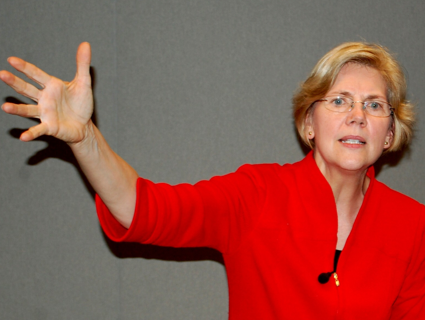

Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.).Mary F. Calvert/ZUMAPRESS.com

She’s going to run and there’s nothing anyone can do to stop her.

So goes the conventional wisdom surrounding Hillary Clinton’s potential bid for the White House in 2016. And why shouldn’t the former Secretary of State be the inevitable Democratic nominee? She’s a household name, a prodigious fundraiser, and well-liked within her own party. In a recent survey by Public Policy Polling, 67 percent of Democratic primary voters said they supported her. Vice President Joe Biden finished a distant second with just 12 percent. The question isn’t Will Hillary run? or Will she win the nomination? It is: Which Republican might she face? That list is long and changing daily: New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie, Sen. Rand Paul (R-Ky.), Gov. Bobby Jindal, Gov. Scott Walker, Sen. Ted Cruz (R-Texas), etc.

Not so fast, Noam Scheiber writes in the new cover story for the New Republic magazine. Clinton is anything but inevitable (remember 2008?), he argues, and in fact there is a Democratic challenger who poses a grave threat to Hillary’s presidential aspirations, an “insurgent” who captures the party’s growing populism and anti-Wall Street fervor better than any other Dem in the party: Senator Elizabeth Warren.

The delightfully bizarre cover of the new TNR dubs Warren “Hillary’s Nightmare,” and Scheiber makes a damn convincing case for why Warren, far more than Clinton, is the candidate most attuned to an angry and disillusioned Democratic base in 2013 (and, presumably, 2016). Scheiber cites poll after poll revealing a Democratic Party—in the Beltway and beyond it—moving closer to Warren’s populist worldview:

Gallup finds that the percentage of Democrats with “very negative” views of the banking industry increased more than fivefold since 2007, while the percentage who have positive views fell from 51 to 31. Between 2001 and 2011, the percentage of Democrats who were dissatisfied with the “size and influence of major corporations” rose from 51 to a remarkable 79.3.

Of course, any prediction of a populist revolt against the party’s top brass must grapple with the tendency of such predictions to be wrong. From the Howard Dean campaign in 2004 to the Occupy Movement in 2011, the last decade in Democratic politics has been rife with heady declarations of grassroots rebellion, only to see the insiders assert control each time. Even the one insurgency that did succeed, the Obama campaign, was quickly absorbed into the party establishment, from which Obama was never so far removed in the first place.

But three developments suggest this time really could be different. The first is that, even at the elite level, the party has changed far more over the last few years than is widely understood. Chris Murphy, the Connecticut senator, estimates that not too long ago, congressional Democrats were split roughly evenly between Wall Street supporters and Wall Street skeptics. Today, he puts the skeptics’ strength at more like two-thirds. Warren told me she attributes this to the disillusionment surrounding Dodd-Frank, which ushered in a range of new regulations but left the details to regulators, who promptly caved.

There is also the fact that, unlike other liberal challenges, this one has broad national reach. The pollster Celinda Lake has found that support for “tougher rules” for Wall Street obliterates party lines, increasing in the last two years from more than 70 percent to more than 80. In South Dakota, a state Mitt Romney carried by 18 points, a recent poll showed Democrat Rick Weiland, an obscure ex-aide to Tom Daschle, a mere six points behind the state’s former Republican governor for a soon-to-be-vacant Senate seat. The animating principle of Weiland’s campaign is that government per se isn’t the problem; the problem is a government taken over by “big-money interests.” The same poll showed voters agreeing with this statement by a 68-to-26 margin.

Scheiber also teases out a fundamental and crucial difference between Clinton and Warren. The Clintons are seen as innately political creatures, the products of three decades spent running for office, raising money, and wielding power. As Scheiber writes, “The long-standing knock on the Clintons…(unfair in many ways) is that they primarily represent the cause of themselves.” Warren has one cause and it is the reason she got into academics, public policy, and, later, politics: improving the lot of working people. Yes, she covets the spotlight and the media’s attention whenever possible, but she does so for the purposes of advancing that cause. It’s an important point that Scheiber does well to highlight:

Everything from her public denunciations of Clinton to her lobbying to lead the CFPB to her eventual Senate run was motivated by a zealous attachment to the cause that has preoccupied her since childhood, not necessarily an interest in holding office. In October of 2010, Eliot Spitzer, the former New York governor, was launching a show on CNN and was thrilled to land Warren as his inaugural guest. But Spitzer planned to open the broadcast calling for Geithner’s head and worried that his monologue might violate some delicate protocol. Geithner was officially Warren’s boss at Treasury, after all. He held a key vote over whether she would run the consumer agency. But when Spitzer offered to skip the diatribe, Warren didn’t even pause to mull it over. “No, it’s fine with me,” she told him flatly.

The threat Warren poses is not lost on Clintonland. Nor is she easily dismissed as another Bill Bradley circa 2000 or Howard Dean circa 2004. Her folksy, working-class message is far too appealing, especially to voters in, say, Iowa (cough, cough). Factor in Warren’s footprint in the Boston media market, which reaches well into first-in-the-nation New Hampshire, and a roadmap to the nomination begins to look somewhat feasible.

Can Hillary and her team can do anything to keep Warren from running? Doubtful. “She has an immense—I can’t put it in words—a sense of destiny,” a former Warren aide told Scheiber. “If Hillary or the man on the moon is not representing her stuff, and her people don’t have a seat at table, she’ll do what she can to make sure it’s represented.” The decision is Warren’s: Is the White House next on her lifelong crusade for working people?

Warren typically denied any speculation about her presidential ambitions for Scheiber’s story, sticking to her talking points. “You’ve asked me about the politics,” she said. “All I can do is take you back to the principle part of this. I know what I am in Washington to do: I’m here to fight for hardworking families.”As for TNR‘s bold prediction, there’s this caveat: In November 2005, the magazine toued then-Sen. Russ Feingold on its cover as “The Hillary Slayer.” You can see how well that worked out.