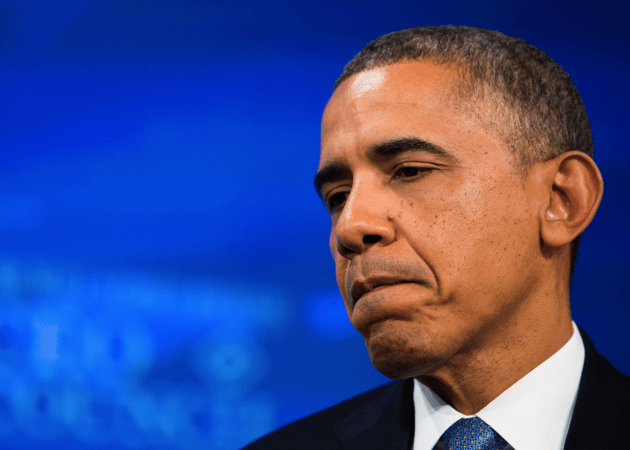

Drew Angerer/DPA/ZUMAPress

Last week, President Barack Obama announced a fix for the millions of Americans who have received health insurance cancellation notices. Insurers will now have another year to offer plans that don’t comply with the Affordable Care Act. But insurance companies probably won’t go along with the president’s plan.

Seven major health insurers—including United Health Group, Humana, and Kaiser Permanente—tell Mother Jones they’re not sure what they’ll do yet, and are waiting for direction from state insurance commissioners, many of whom have yet to decide whether they’ll back Obama’s idea. But health care experts say it’s likely that many insurance companies will not adopt Obama’s fix, because doing so would be an administrative hassle and create uncertainty, costing insurers money.

“Insurers want certainty, set rules, and the ability to…set prices…and make a profit,” explains Lawrence Jacobs, a political science professor at the University of Minnesota and coauthor of Health Care Reform and American Politics.

Obama’s fix, which will have to be implemented before the end of the year, messes with all that.

Because nothing like the Obamacare fix has happened before, it will be difficult for insurers to anticipate which of their customers might want to keep their old plans. If older, unhealthier people end up being more likely to hang on to their plans, insurers’ costs would be higher. If younger, healthier people end up being more likely to hang on to their plans, insurers’ costs would be lower. Without being able to predict the age and health of the people who will decide to keep their plans, insurers will have a difficult time setting premium rates. Companies worried that they won’t be able to predict customers’ behavior and will end up undercharging for uncanceled plans may want to play it safe and avoid Obama’s fix, Jacobs says.

The president’s plan is also a huge administrative burden on companies, explains Jon Gruber, an MIT economist who helped design the Affordable Care Act. In addition to trying to predict which of their customers will want to keep their plans, insurers who want to reissue plans will have to reassess patients’ health status. Both tasks will have to be completed before the end of the year. If insurance companies avoid the president’s suggestion that they renew canceled plans, it will be at least partly because of the “the hassle of doing it,” Gruber says.

Those administrative hassles will also cost insurers money. Companies will have to pay for all the extra labor hours involved in turning canceled plans around, not to mention the thousands of stamps needed to send out all those un-cancellation notices and customer service hours spent dealing with ever-more-confused customers. Obama offered to pay part of the administrative costs his plan would entail. But the administration won’t cover the whole bill. So many insurance companies may decide to ignore Obama’s fix and skip the added expense.

Insurance companies’ reluctance isn’t the only hurdle. Obama’s fix faces other obstacles, too. To work, Obama’s fix relies on an “unlikely chain of events,” Jacobs says. State insurance commissioners, who don’t like the plan, would have to approve it. Then insurers would have to take on the risk of continuing to offer old policies. Finally, consumers would have to decide it’s a good idea to stick with their old plans—many of which cover so few benefits they can hardly be termed insurance. “My hunch is that [Obama’s fix] won’t have the effect people worried about,” Jacobs says.

A legislative fix to the cancellations is unlikely, too. Senate bills introduced earlier this month by Democrats Mary Landrieu (D-La.) and Mark Udall (D-Colo.) would force insurers to keep offering plans that have been canceled under Obamacare. A GOP-sponsored keep-your-plan bill that the House passed last week would essentially delay Obamacare for a year, by allowing everyone—not just those with canceled plans—to buy plans that are not compliant with Obamacare. The two chambers’ bills differ too widely for Congress to agree on a compromise, Jacobs argues.

Even if Congress could agree on a legislative fix, Obama is unlikely to sign on, says Tim Jost, a health care scholar at Washington and Lee University School of Law. The president already threatened to veto the House bill, and the Senate bills infringe on the rights of states and private companies far more than the president’s fix, and would be politically unpopular, Jost says.

Obama and Senate Democrats have been pressuring insurance companies to play along and let consumers keep their old plans. But Jacobs says Dems and other supporters of health reform should lay off, and just accept that Obama’s fix won’t have much of an effect. It will do “minimal damage,” he says, and give “Obama and Democrats a patina of political cover” while the administration fixes the problems with its insurance website so that it can deliver new, better plans to Americans whose plans have been canceled.