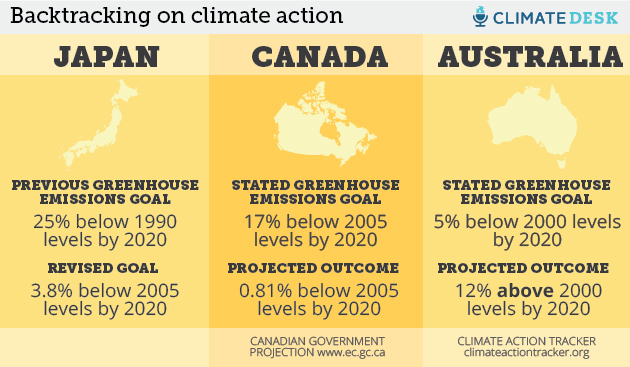

When Japan dramatically slashed its plans last week for reducing greenhouse gas emissions by 2020, from 25 percent to just 3.8 percent compared to 2005 figures, the international reaction was swift and damning.

Britain called it “deeply disappointing.” China’s climate negotiator, Su Wei, said, “I have no way of describing my dismay.” The Alliance of Small Island Nations, which represents islands most at risk of sea level rise, branded the move “a huge step backwards.”

The decision was based on the fact that Japan’s 50 nuclear reactors—which had provided about 30 percent of the country’s electricity—are currently shuttered for safety checks after the Fukushima disaster in March 2011, despite the government trying to bring some of them back online. That nuclear energy is largely being replaced by fossil fuels.

Japan’s announcement has cast a shadow on this week’s climate negotiations in Warsaw. Bill Hare, CEO of Climate Analytics and a former lead author for the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, described the mood as “a downward spiral of ambition” which is “undermining confidence in the process and the ability to move forward.”

Elliot Diringer, the executive vice president of the DC-based think tank Center for Climate and Energy Solutions, says NGOs and policymakers are feeling frustrated: “There was a great deal of sympathy for Japan in the aftermath of Fukushima,” he says. “And that’s now converted to disappointment.”

But Japan isn’t the only industrialized country at Warsaw walking away from previously stated climate goals and attracting criticism for throwing a spanner in the works, an issue also explored here in Grist. Australia and Canada are emerging as strong opponents of more aggressive climate action and are likely to come up short on their commitments to reduce their emissions.

Australia Guts Carbon Policy

Sweeping to power on a carbon tax backlash in September this year, Australia’s new prime minister, Tony Abbott, has wasted no time in shifting the country’s policy course—and rhetoric—on climate action.

The conservative government is dismantling the country’s market-based carbon pricing laws in the parliament as a matter of first priority, and replacing it with its own system, “Direct Action,” a $3 billion plan to fund projects that it says will help lower emissions. The problem is not many people believe it will work. Analysis by Climate Action Tracker, which assesses reduction programs around the world, shows that rather than cutting greenhouse gases by the promised 5 percent, the policy will actually increase emissions by 2020 by 12 percent compared to 2000 levels. Independent modeling shows that even if the government stuck to its 5 percent pledge, it couldn’t be met without coughing up an additional $3.7 billion.

Australia’s new policies are “registering shock,” in Warsaw, says Hare, who also helps run Climate Action Tracker. “It’s being met with disbelief.”

At the Warsaw talks, Australia is contributing “to a sense that there’s some unfortunate backsliding among some countries,” Direnger says.

Abbott asserted last week that the goal will be met, but he added that no further money would be spent on the program if it wasn’t: “We will achieve it with the Direct Action policy as we’ve announced it and that policy: It’s costed, it’s funded, and it’s capped,” he told the Australian Broadcasting Corporation. The Australian Conservation Foundation accused the government of abandoning its promise to scale its original pledge up to 25 percent if there’s stronger global climate action, calling Abbott a “deal wrecker.” The opposition Labor party said the government was allowing “big polluters open slather in the future.”

A flurry of other developments Downunder have helped to cement the new government’s stance at home and abroad:

- There are plans to kill three key organs of the previous government’s climate policy entirely: the independent Climate Commission, the Climate Change Authority, and the Clean Energy Finance Corporation.

- The budget for the Australian Renewable Energy Agency will be slashed by $435 million over the next three years

- For the first time since the 1997 Kyoto agreement, Australia declined to send its environment minister, Greg Hunt, to this week’s international climate talks talks, saying the business of repealing the carbon legislation in the first two weeks of parliament was too important.

Canada Unlikely to Meet Its Own Targets

Australia is among the developed world’s worst polluters in terms of of CO2 per capita. But Canada is not far behind its Commonwealth compatriot. Lately, they seem to be enjoying each other’s company.

This week, both conservative governments opposed a push at the Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting in Colombo, Sri Lanka, to establish a green capital fund for small island states and poor African countries to address climate change. Canada recently praised Australia’s decision to repeal its carbon tax: “The Australian prime minister’s decision will be noticed around the world and sends an important message.”

When Canada signed the Copenhagen Accord in 2009, the country committed to reduce its greenhouse gas emissions to 17 percent below 2005 levels by 2020 (bringing it in line with US goals). But last month, the Harper government admitted it’s going to blow past that target by a wide margin. Environment Canada, the federal ministry that looks after climate policy, issued a report that said that without new government action, the country’s emissions will be 20 percent (or 122 megatons) higher than the country committed to at Copenhagen. This amount is barely below 2005 figures.

It’s this trajectory that, in part, led the Climate Action Network Europe and Germanwatch to list Canada as the worst performing country among all industrialized nations in their annual performance index—unchanged from last year’s ranking: “Canada still shows no intention of moving forward with climate policy and therefore remains the worst performer,” the report states. (In December 2011, Canada was the first country to formally withdraw from the Kyoto Protocol).

Reading the tea leaves doesn’t inspire much optimism: All of this is happening against the background of expanding tar sands development. The report from Environment Canada predicts that without a change in policy, CO2-equivalent emissions from oil sands are projected to increase by nearly 200 percent by 2020 over 2005 levels. And on tar sands, the Harper government shows no sign shifting policy direction.

The combined effect has an “ultimately corrosive effect on the ability to secure a strong international agreement if the major players aren’t playing,” Hare says.