In a 1988 op-ed for her college newspaper, Liz Cheney, the daughter of Vice President Dick Cheney who is now running for the Republican Senate nomination in Wyoming (and kicking up a family feud and a GOP civil war), had a stern message for anti-apartheid activists campaigning for freedom in South Africa: “frankly, nobody’s listening.”

The Cheney family has a complicated history regarding South Africa and the effort to end the racist regime that ruled that nation for 46 years. When he was a congressman, Dick Cheney voted against imposing economic sanctions on South Africa’s apartheid government and opposed a resolution calling for Nelson Mandela to be released from prison, saying Mandela was a “terrorist”—a position Cheney defended as recently as 2000, when he ran for vice president. Liz Cheney, who is hoping to unseat three-term GOP Sen. Mike Enzi, has not spoken publicly on Mandela since his death last week. Her campaign did not respond to a request for comment.

In the 1980s, when Liz Cheney was attending Colorado College, a campus group called the Colorado College Community Against Apartheid led regular demonstrations to push the college to adopt a policy of divestment—a form of economic protest in which the college would agree not to invest in companies that had business interests in South Africa. Throughout the country in those years, students at universities and colleges were pushing administrations and boards to dump their investments in firms that engaged in commerce with South Africa, including such corporate powerhouses as IBM. The Colorado College group, as did protesters on other campuses, constructed a “shanty town” on the quad, and it organized an on-stage demonstration at the school’s 1987 graduation ceremony. That year’s commencement speaker: Liz Cheney’s mother, Lynne.

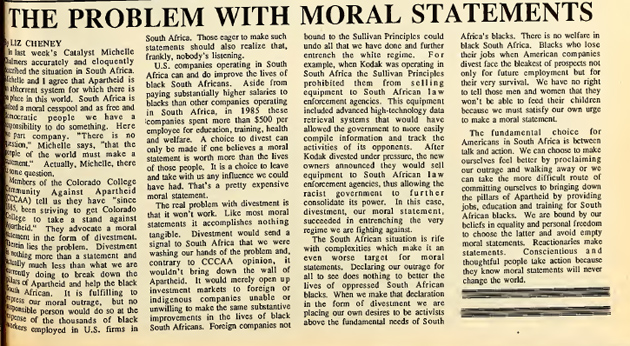

In her op-ed for the Catalyst, Liz Cheney did refer to the white South African regime as a “racist government” that had “oppressed South African blacks.” But she argued against punitive economic action—and dismissed the entire divestment movement.

“South Africa is indeed a moral cesspool and as free and democratic people we have a responsibility to do something,” she wrote. But divestment, she argued, would amount to an empty gesture: “It is fulfilling to express our moral outrage, but no responsible person would do so at the expense of the thousands of black workers employed in U.S. firms in South Africa.”

“We can choose to make ourselves feel better by proclaiming our outrage and walking away or we can take the more difficult route of committing ourselves to bringing down the pillars of Apartheid by providing jobs, education and training for South African blacks,” she wrote. echoing the argument that had long been made by conservatives opposed to divestment who claimed that economic engagement with the racist state would eventually bring change. She pooh-poohed divestment as nothing but a hollow and meaningless gesture: “Reactionaries make statements. Conscientious and thoughtful people take action because they know moral statements will never change the world.”

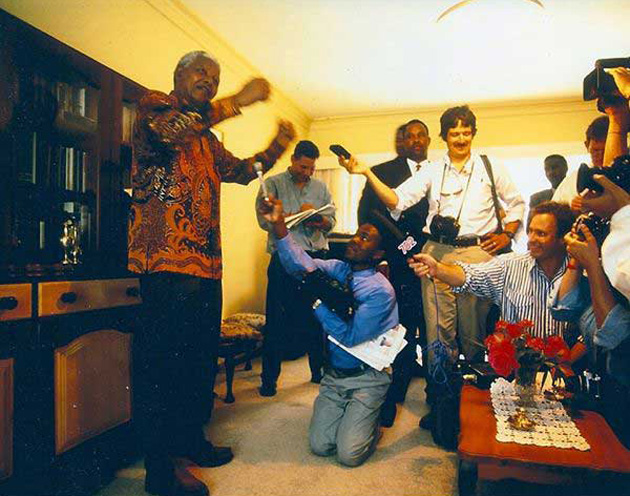

Mandela, his African National Congress, and their supporters in South Africa and around the world backed divestment as a means to bring about the end of the apartheid regime. And on his first trip to the United States after being released from prison in 1990, Mandela visited Berkeley, California, which in 1979 became one of the first American municipalities to divest from South Africa. In 1986, the entire University of California system divested $3.1 billion in assets from South Africa—an event Mandela said helped drive the stake through the heart of apartheid. “We salute the state of California for having such a powerful political stance on divestment,” he said during that 1990 trip.

Ultimately, Cheney’s argument won out on her campus. Colorado College was not one of the 167 American educational institutions to divest its financial resources from South Africa in the late 1970s and 1980s, despite CCCAA’s efforts. In affirming the school’s policy in 1987, Citicorp president William Spencer, a Colorado College trustee, warned that divestment could “contribute to a ‘revolutionary upheaval’ and ‘massive loss of life'” in South Africa.

Read Cheney’s full piece: