Photoillustration by Nina Liss-Schultz

As the Obama administration continues to unsuck its health care website, one questions lingers: How did this important government project get so screwed up? If you ask technologist Clay Johnson, the insurance exchange’s problems began, in a way, in 1995, when “Congress decided to lobotomize itself.”

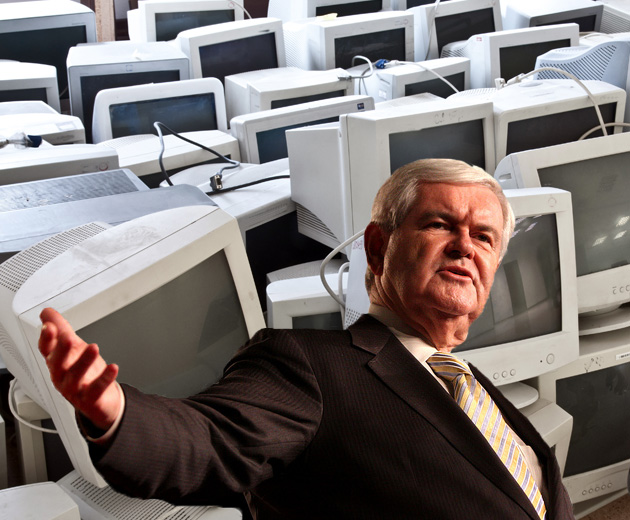

Johnson was referring to a specific action lawmakers took then: They killed a tiny federal agency called the Office of Technology Assessment. Established in 1972 as Congress’ nonpartisan in-house think tank, the OTA studied new technologies and offered recommendations on how Washington could adapt to them. But then Speaker of the House Newt Gingrich (R-Ga.) turned off its lights.

Today, members of Congress have legislative counsels to help draft laws. They have the Congressional Budget Office to analyze how much laws will cost. But they don’t have the OTA’s experts to tell them how those laws will work.

“An OTA review might have prevented some heartburn and embarrassment” associated with the Healthcare.gov rollout, argues Rep. Rush Holt (D-N.J.), an astrophysicist who has previously introduced legislation that would resurrect the agency.

Warning Congress about problems with Healthcare.gov—and explaining them—would have been right in OTA’s wheelhouse. The office, Rep. George Brown (D-Calif.) dryly remarked in 1995, was a “defense against the dumb.” During its 24-year existence, the agency developed a reputation for sharp, foresighted analysis on the problems of the new information age: It called for a new, reinforced tanker design a decade before the Exxon-Valdez spill; emphasized the danger of fertilizer bombs 15 years before Oklahoma City; predicted in 1982 that email would render the postal service obsolete; and warned that President Ronald Reagan’s Strategic Defense Initiative (better known as “Star Wars”) would likely result in a “catastrophic failure” if it were ever used.

Analyzing health care spending was one of OTA’s specialties. One of its final reports, “Bringing Health Care Online,” published in 1995, focused on the potential (and potential for mishaps) in electronic data interchanges. “Changes in the health care delivery system, including the emergence of managed health care and integrated delivery systems, are breaking down the organizational barriers that have stood between care providers, insurers, medical researchers, and public health professionals,” the report warned.

But thanks to Gingrich and the Republican Revolution, that OTA review of potential hurdles for the Obamacare website never happened. In 1995, Gingrich set the OTA’s funding to zero—and gave the ax to similar agencies, like the General Accounting Office (which lost half its funding) and the Agency for Health Care Policy and Research (which was phased out). He told members of congress with tech questions to consult their local research universities instead.

Gingrich’s decision didn’t save the government much money. As Mother Jones‘ Chris Mooney noted, the agency was remarkably cost-effective. One OTA report on the usefulness of technological upgrades at the Social Security Administration yielded $368 million in savings—well more than the yearly budget of the 143-member agency—and prevented SSA from investing in a clunky, overly expensive computer program. But Gingrich had promised to trim the size of the government, and cutting a small agency was easier than eliminating a big one. “It was a way to claim that you had shut down an agency, but it really didn’t cost anything [to run],” says Peter Blair, a former OTA director who wrote a book about the agency. Besides, Republicans had found some of the agency’s hard truths—such as the Star Wars fact-check and warnings about climate change—to be increasingly politically inconvenient. They liked having experts to turn to, but not when it undermined their agenda.

OTA’s demise has worsened tech illiteracy on Capitol Hill, Holt says. Johnson, the technologist, compared one recent House hearing on Obamacare to “people who can’t read doing literary criticism.” Slate‘s David Auerbach characterized the same hearing as a “spectacle of tech illiteracy.” In a 2013 survey by Federal News Radio, 85 percent of congressional staffers said they did not believe “members of Congress have the knowledge/background they need to properly legislate” tech issues. The late Alaska Republican Sen. Ted Stevens’ famous reference to the internet as a “series of tubes” typified the problem. As one staffer surveyed by Federal News Radio put it, “For the kind of legislation needed in these high-tech areas, Congress may as well be debating the logistics of brain surgery.”

(Update: As readers have noted, Lorelei Kelly of the New America Foundation, a DC think tank, has been pushing the ‘lobotomy’ language even before Johnson, publishing a report as recently as last December warning of the serious consequences of eliminating OTA.)

Unlike some of his colleagues, Bruce Bimber, a professor at University of California-Santa Barbara who also wrote a book about OTA, isn’t so sure the OTA would have made a difference on Healthcare.gov. But he agrees on one thing: The agency’s voice is sorely missed on the policy debate of the 21st century. “Congress has a problem with too much information, not too little,” Bimber says. “One of the things that OTA was really good at was being able to sift through that and figure out what is and isn’t a problem.”

Prominent Democrats have long pushed for OTA’s resurrection. Hillary Clinton promised to restore the agency as part of her 2008 presidential campaign platform; so did Al Gore eight years earlier. But in Holt’s view, the agency’s biggest enemy isn’t Republicans—it’s inertia. Previously, his OTA efforts have come in the form of amendments to spending bills. But there haven’t been any new spending bills so far this year. “Congress just isn’t doing anything,” Holt says. “So I suppose some might argue that therefore we don’t need OTA.”