Soldier: <a href="http://www.shutterstock.com/pic-124270684/stock-photo-military-young-man-studio-portrait.html?src=same_model-124270678-3">Ysbrand Cosijin</a>/Shutterstock; Sticker: <a href="http://www.flickr.com/photos/70097310@N00/2277408667/in/photolist-4tfjfF-5zynEX-5zoxrW-5zokhW-5zoxdN-drkHL8-drdjvY-4qjgEp-8i7DGy-5zn4cM-5zrkdS-5zrkpq-5zn45T-5zn49R-5zn48t-rMh3C-5Ep8Yx-rLrhm-i1fQt5-8QAzqP-5zqg4S-eH7vd-4qkyf8-5zKbaV-8QDFv9-8PBHds-5zm6fJ-5C5Vgm-5xyTuC-driiPW-dri94V-on8sG-driDkB-Lvin9-5zZ8rp-dZVVnj-5ziMXX-4qotMs-5znqYP-drcNVq-8QshrR-4qscko-4yGYyY-8QnLXS-5y1Btd-5zjcYV-aXtMCP-5ywLK4-4p1Xi1-53tGVX-4AbEK2">yaquina</a>/Flickr. Photoillustration by Matt Connolly.

Last month, I collected reports from voters across the United States who had trouble casting a ballot because of the growing number of strict voter identification laws. When Ben Granger, an Air Force captain who was deployed during the 2012 presidential election read the piece, he came forward with his own story—about the time he was turned away from voting for the US president by a conservative county in Texas, after mailing his ballot from a war zone.

Texas has come under fire for its new law requiring poll workers to apply extra scrutiny to voters’ state identification, in a way that potentially discriminates against married women. Although voter ID laws garner the most attention for turning voters away from the polls—longstanding laws in Texas and other states still require election boards to use a voter’s signature to verify absentee ballots.

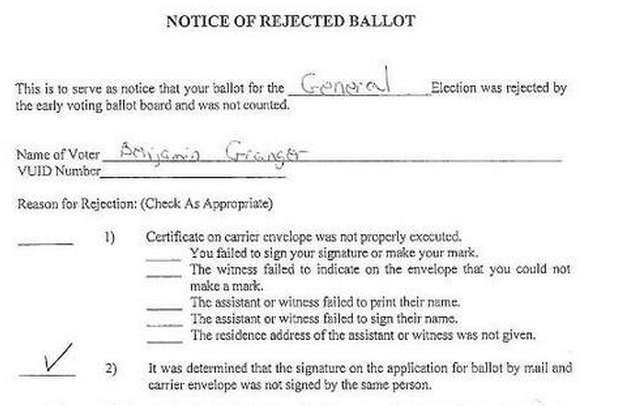

Granger, who was deployed for seven months in Kandahar Province, Afghanistan in 2012, says he’s voted in every presidential election since he turned 18. But after he sent his absentee ballot to Tom Green County, Texas, to vote in the 2012 general election, he received a rejection notice claiming that his vote was discarded because his signature on the ballot application and the signature on the ballot’s envelope were signed by different people:

“I was surprised and aggravated,” says Granger, who, having spent four and a half years on active duty, now lives in Belleville, Illinois, supporting U.S. Air Force Air Mobility Command on active reserve. “As the guy that requested the ballot, carefully looked over the candidates, carefully signed the envelope and the ballot with a good pen, and then walked across my base to the post office to mail it personally, the rejection was insulting.”

Under Texas law, in order to vote by absentee ballot, a voter must sign a ballot application, and then after receiving the ballot some weeks later, must sign the sealed ballot’s carrier envelope. In Tom Green County—where 73 percent of residents cast a vote for Mitt Romney last November—the law allows a county to appoint a five-person board tasked with deciding, by majority vote, whether the two signatures match (they can even request to see the voter’s registration signature). In Granger’s case, they claimed that the application and the ballot envelope were signed by different people. He adds that while he doesn’t specifically remember signing the application before successfully receiving his ballot about six weeks later, “I was pretty busy at the time…I [always] sign my name the same way.”

This law is much older—more than a decade—than the one requiring that poll workers make sure a voter’s driver’s license “substantially” matches the name on the voter registration. Marian Schneider?, an attorney with the Advancement Project, a voting rights group, says that “every state has a process where they compare a voter’s signature with another signature on file”—even if you vote in person—and she doesn’t necessarily consider that a barrier to voting, in the way that voter ID laws are. But she notes that incidents of people committing fraud and forging signatures are nonetheless, “exceedingly rare.”

Logan Churchwell, a spokesman for True the Vote, which argues that voter fraud is common, says that checking signatures is a good way to stop a criminal from “purchasing a ballot in a military installation and sending it on someone else’s behalf.” (There were only 13 credible cases of in-person voter impersonation between 2000 and 2010.) Churchwell doubts Granger’s claim of voter suppression.

But Doug Chapin, the director of the Program for Excellence in Election Administration at the University of Minnesota, says that barring people from voting because their signatures don’t match “is a growing problem in the field” and “an issue that’s increasingly on the radar.?” While every state has a different process for verifying signatures, “This example is definitely at the stricter end,” he says. Rick Hasen, a voting expert and law professor at the University of California, Irvine, agrees that, “signature matching has been studied and it is not a perfect system.” (Kansas has? done away with it entirely, allowing voters to enter a verification number, such as a driver’s license or social security number, instead.)

Granger says that if the Election Board truly thought someone had stolen his ballot envelope or application, “isn’t that cause for the launch of a criminal investigation?” Vona McKerley, the election administer in Tom Green County, tells Mother Jones that “several” ballots were turned away in last year’s election because of non-matching signatures. “The ballot board was following the law as prescribed in processing the ballots. No, there was no investigation.”?

Granger is, nonetheless, concerned that this is just another way to disenfranchise voters: “I am a young educated military officer and I know how to sign my own name for God’s sake. And even if I didn’t, is poor penmanship good cause for disenfranchisement? What about the elderly whose hands may shake?”?