A woman shelters in the "Widow's Basement" in Baba Amr, Homs, Syria, in February 2012. It was one of the few underground shelters at the time.Paul Conroy

Syria is the deadliest place in the world for journalists, the Committee to Protect Journalists said Monday, with 29 killed in the country in 2013—more than the next five countries combined. Since March 2011, when a revolt to oust President Bashar al-Assad began, 69 journalists have been killed. One was legendary war correspondent Marie Colvin, who died while on assignment for the UK’s Sunday Times in February 2012 when Assad’s forces shelled the building she had taken shelter in in Homs, Syria.

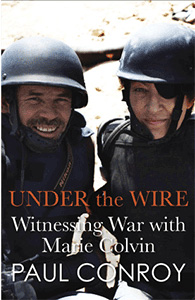

Photo journalist Paul Conroy was with Colvin and sustained a leg injury big enough to stick his fist through. In his new book, Under the Wire, he chronicles the days leading up to the deaths of Colvin and French photo journalist Remi Ochlik with vivid detail and sardonic British wit (he joked as much about crappy coffee in Baba Amr being the death of him as the Syrian government). I talked to Conroy about life in Syria, Colvin’s death, and how gallows humor helps reporters survive hell on earth. He also shared some of his never-published photos from the assignment, which you can see below.

Syria has been out of the headlines since the chemical-weapons deal was reached earlier this year. What’s going on inside the country?

The situation in Syria has descended to a level which ought to shame the world. For nearly three years now, Bashar al-Assad has used his vast arsenal of Russian-supplied weapons to unleash explosive hell on innocent civilians. More than 110,000 people have now died from the use of conventional weapons.

The window of opportunity for viable intervention, safe havens, no fly zones and humanitarian corridors, passed years ago. Syria was left in a vacuum, and that vacuum was filled by the jihadists, extremists who exploited the world’s unwillingness to consider any form of intervention. A heavy price is now being paid for this collective error of judgment.

Britain, along with the USA, is war weary and, after the travesty of Iraq and Afghanistan, has grave misgivings in any future involvement in the Middle East. The ghost of Tony Blair and his single minded determination to attack Iraq, at any cost, has cast a long shadow over British politics. The British public have a long collective memory. The fact that our Prime Minister lied over WMD has deteriorated further our trust in the political class. The people who have suffered most from this political mistrust are the helpless civilians in Syria who reached for a helping hand, yet found only a fist.

Russian President Vladimir Putin said that perhaps it was the rebels who staged a chemical weapons attack. What do you think of that?

The polite answer to that is ‘complete rubbish,’ my heartfelt answer is, ‘utter bollocks.’ I spent time with these people; they are fighting for their lives, for survival. They showed Marie and I warmth that went beyond the need to get western journalists in and out of the country. People died on our behalf, they died in an effort to show the world the horrors of what was happening to their own people and families. The concept that they gassed their own families to garner Western support is an anathema to me.

The reality is that although Assad claims they are chemical weapons that can be made in a kitchen, the delivery systems are not something the rebels posses. These people are using medieval catapults to deliver homemade bombs.

In the book you talk about how Assad’s forces knew they were shelling a media center. Why do you think he was targeting journalists?

The night before Marie and Remi’s murder, Marie had given three interviews, to CNN, C4 in the UK, and the BBC World Service. The next morning I could clearly define the firing pattern of the regime gunners. They were bracketing in on us, which is adjusting fire with the use of a drone, until they had precisely targeted the building. They then fired four rockets directly into the media center.

Why? What was happening in Baba Amr was wholesale slaughter, Marie had the audacity to report live from the scene. We had witnessed the butchery and that crossed the boundaries as to what the regime would tolerate. We rattled too many cages in Damascus.

How is your leg doing after all these operations?

Given the state of my leg after the attack on the media centre I can’t complain! I was shocked, but amused, to learn that the medical team were taking bets to see who could put their hands furthest through my leg. My surgeon, Dr. Parri Mohana, succeeded, getting her arm through to the elbow.

I don’t think I will ever play for England but, after 20 operations, I can now walk in straight lines and am pretty mobile again.

You and Colvin got out of Syria and then went back in. Does that decision haunt you? Would you do it again?

I made it clear to Marie that I had a funny feeling about this one. I don’t regret saying that at all. I was speaking my mind, we discussed it and we both went back. It was the right thing to do. It’s what we do and Marie died doing what she did best in life.

You’ve said you wrote the book in four to five-hour sessions where you were balancing between morphine and pain. What was that like?

Initially writing was physically impossible; I was on large doses of mind-numbing drugs. I opened a file on my laptop and titled it ‘The Book,’ but, no matter when I tried to write, I could not get into the mythical rhythm of which other authors spoke. ‘The Book’ remained a white, blank and rather worrying document—I had a deadline to meet.

I woke one morning, it was 4 a.m. and the world was still sleeping. I rolled a cigarette, made some coffee and had a bright idea; maybe I should try writing now. The pain in my leg wasn’t too bad and, more importantly, my head felt as clear as it had in a long time.

It worked like magic. The writing fairy, my chosen name for whatever it was made me sit and write for five hours a day, visited the next night and the next. Eventually, I had a book. My only fear was, that with all the morphine and other drugs, I had written a wartime version of Fear And Loathing.

The book is quite funny, which I found surprising.

I can honestly say, from my perspective at least, without humor you could not do this job. It’s a vent, by which some of the ghastly and traumatic scenes we witness can be made a little less real and a touch more surreal, which helps more than you would expect.

In Misrata, Libya, Marie and I used to travel daily up and down the front line. As the rebels pushed government troops further from the centre where we were based, the journey got longer. One day, when having a laugh and joke with commander Ali, whom we visited regularly, I asked him to help me to convince Marie we should cut out the travel and stay on the frontline. We agreed that a small concrete building, which was pummeled by rockets and mortars every day, should be our mythical home.

The next day when we visited, I started to complain about the length of the journey back and forth to Misrata. Commander Ali, with perfect comic timing, said he had a place we could crash for the night, Marie looked slightly worried. When she asked Ali where it was, he simply nodded towards the concrete block. As he did so, a mortar landed on the roof. We couldn’t keep up the pretense, both Ali and I were laughing so hard, Marie cottoned on to us and the language she used is unprintable.

It sounds like Marie was a close friend. How are you dealing with her passing?

I never got to say goodbye to Marie, her death was instant. But I think writing the book gave me the opportunity to say a proper goodbye. That’s not to say I don’t wake, almost every day, and hope I get a call from her with a crazy plan to get into somewhere we shouldn’t be going.

Why was it important to share this story?

Marie was the archetype war correspondent. She was brave, tenacious and devoted, not only to her job, but also to the real victims of war, the civilians who bore the brunt of corrupt and vicious dictators. She genuinely believed she could make a difference.

The book is part tribute to Marie, but also to the many nameless heroes who helped us to get into Syria and Baba Amr to tell the story. Marie and Remi died telling a story of brutality that continues to this day. I sincerely hope that I have done justice to the bravery of my friends, but also have recorded a small part of history, the death of Baba Amr and its citizens, for those in the future to read an honest account, often lost in the fog of war.

What should journalists take away from the work you and Marie have done?

The tenacity with which we approached our subjects. We both instinctively knew that if we pushed further, harder and asked the questions many would shy away from, we would end up with as near to we could get to the truth. That’s what our job is about, cutting through the myriad layers of half-truths, the smoke and mirrors of war, corruption, deception and sheer bloody horror.

A shorter review originally appeared in our November/December issue of Mother Jones.