<a href="http://www.thinkstockphotos.com/image/stock-photo-toddler-in-a-shopping-cart/AA036661/popup">Ryan McVay</a>/Thinkstock

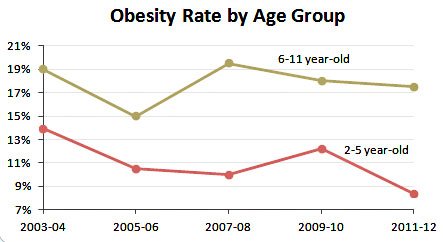

Researchers are still exploring what factors caused the early childhood obesity rate to plummet 43 percent over the last decade. But a group of health experts at the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill think that they have found at least part of the answer: changes to the federally funded Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children that gave poor mothers the means to purchase more fresh produce for their children.

This program, which is better known as WIC, provides billions of dollars per year in nutritious food vouchers for low-income pregnant women, breast-feeding women, and children younger than five. WIC was created in the 1970s, but it wasn’t until 2009 that it provided mothers with vouchers for fruits and vegetables. That’s the change that the North Carolina researchers think may have contributed to the stunning decline in obesity rates.

Barry M. Popkin, a UNC nutrition professor, and two colleagues recently finished a massive study, to be published in the March 2014 issue of the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, of the calorie consumption of US households from 2003 to 2011. During this time period, Popkin says, households with children purchased fewer calories every year. That pattern persisted even after researchers controlled for the effects of the recession. For the later years covered by the study, Popkin links the decline to WIC.

Republicans looking to slash federal spending have targeted WIC in recent years. In March 2012, for example, the GOP-controlled House of Representatives tried to cut $243 million from WIC. The cut, which did not become law, “would have resulted in WIC having to turn away hundreds of thousands of eligible applicants,” write Zoë Neuberger and Robert Greenstein, analysts for the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, a progressive think tank.

About 9 million low-income mothers and children are enrolled in WIC, which also provides parents with health care referrals and nutrition advice. In 2011, the program served about half of all eligible infants born in the United States. The 2009 changes, which were based on a two-year study of which nutrients were absent the diets of low-income mothers and young children, were the first substantial shifts in benefits since the program was established. Under these new rules, a woman and child got $14 a month for produce. (Subsequent bills have boosted that to the current level of $16 per month.)

The US Department of Agriculture, which runs the program, also cut back on funding for dairy and juice purchases, and began allowing enrollees to buy beans, whole grains, and baby food. And states were free to make some additional changes that would bring WIC more in line with modern dietary recommendations.

“About half of the states went above and beyond,” says Popkin, by cutting back even more on dairy products, juice, and sources of saturated fats than new federal regulations required. “Even when you looked at conservative states, half of them went whole hog.”

The difference that WIC made to childhood health was foreshadowed by reports, last year, from health officials in 18 states, who saw WIC-enrolled preschoolers enjoying a slight decrease in obesity rates.

In 2012, in a study published in the Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, a team at Yale University found that the changes to WIC had begun to erase some of the country’s food deserts.

“We visited 300 stores in Connecticut before and after the changes to WIC,” says Tatiana Andreyeva, one of the researchers. “And after those changes, we saw a lot more healthy foods in grocery stores in lower-income neighborhoods that didn’t have them before—whole wheat, bread, low-fat milk, fruits and vegetables.”

Despite these benefits, Republican-proposed cuts and congressional inaction have repeatedly put funding for WIC in jeopardy. Unlike Social Security or Medicare, not everyone who is eligible for WIC is guaranteed to get it.

For most of WIC’s recent history, this hasn’t been an issue. “Since 1997, there has basically has been a bipartisan commitment that has been adhered to by Congress and every administration to provide enough money so that all eligible applicants can be served,” Neuberger says. “The goal is that nobody who qualifies is turned away for lack of funds.”

But since taking control of the House of Representatives in 2011, Republicans have persistently challenged WIC’s funding levels, starting with those proposed cuts in 2012.

“2013 was another very difficult year,” Neuberger says. Because Congress could not pass a budget, “the program operated…with total uncertainty about its funding level for the second half of the year.” As a result, many of the state offices that administer WIC laid off staff, closed or consolidated field offices, or cut back their office hours. All of this prolonged waits for WIC eligibility and made it harder for low-income parents who work long hours to apply for benefits. The program also narrowly avoided running out of money during the government shutdown of 2013.

None of the cuts proposed in the GOP-run House have become law—they have been blocked by the Democrat-controlled Senate. But Neuberger notes that this doesn’t mean WIC’s is guaranteed for the future. “We’re likely to go through the same cycle of uncertainty again,” she says.