Ref: Daniel Goncalves/Cal Sport Media/ZUMA; Flag: <a href="http://www.shutterstock.com/pic-50647975/stock-photo-a-yellow-penalty-flag-on-a-white-background.html?src=HRL7bURq9TMZqUzN8VTz9w-1-0">Mike Flippo</a>/Shutterstock; Rainbow: <a href="http://www.shutterstock.com/pic-30374881/stock-photo-rainbow-flag-with-a-blue-background.html?src=9xz9zJ0qS35j_zwVI3xeqA-1-120">Rikke</a>/Shutterstock. Photoillustration by <a href="http://develop.motherjones.com/authors/matt-connolly">Matt Connolly</a>.

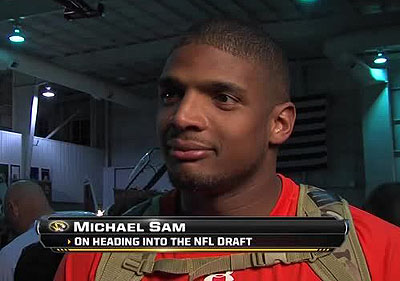

University of Missouri All-American defensive end Michael Sam shocked the sports world Sunday when he announced that he is gay. The National Football League has never had an openly gay player, and the timing of his announcement—just weeks before the league’s so-called combine, when draft-eligible players like Sam are put through the paces in front of scouts and team executives—has been hailed as incredibly brave.

But as Kevin Drum noted Sunday night, a group of NFL front-office types had a different take. Several team executives anonymously questioned Sam’s talent and pro prospects in a SI.com article published after his announcement. Sample line, from a personnel assistant: “I don’t think football is ready for [an openly gay player] just yet. In the coming decade or two, it’s going to be acceptable, but at this point in time it’s still a man’s-man game.” Worse still, some of them argued that teams would lower Sam on their draft boards, or not draft him at all, simply because he’s gay.

Is that legal? Do state and local laws protect potential draftees from discrimination based on sexual orientation? And what about the NFL’s own nondiscrimination policy? Here’s a brief explainer:

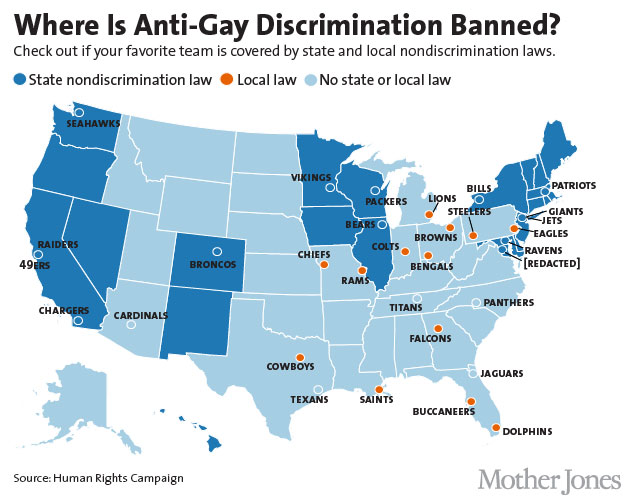

What sorts of nondiscrimination laws are on the books? Because the federal Employee Nondiscrimination Act (ENDA) died in the House last year, there is no nationwide law protecting employees and job candidates from discrimination based on sexual orientation. However, 21 states and the District of Columbia and nearly 200 municipalities have such nondiscrimination laws. Currently, 27 of 32 NFL teams are in jurisdictions that have some sort of state or local law prohibiting discrimination against gay employees:

What does the NFL’s nondiscrimination policy say? In 2011, the league and the NFL Players Association added an anti-discrimination policy to their latest collective bargaining agreement. “Players and owners believed it was important to include, because we anticipated needing to protect players from discrimination if this very issue came up,” says George Atallah, the assistant executive director of external affairs for the NFLPA.

Then, following last year’s NFL combine, controversy erupted when it was reported that prospective players were being asked questions like “Do you have a girlfriend?” and “Do you like girls?” The New York attorney general’s office reminded league officials that such questions constitute discrimination under state law. (The NFL is based in Manhattan.) The union chimed in as well. “We’ve raised those concerns with the NFL with respect to unprofessional lines of questioning during a job interview,” Atallah says. “We believe that they have heard our concerns, but there’s always room to do more. More, specifically, on the enforcement side. If the NFL can fine a player for wearing one sock higher than the other, then certainly they can pursue violations of professional conduct for team personnel.”

Or, as New York Attorney General Eric Schneiderman told Mother Jones in a statement: “No American should face barriers to professional advancement because of their sexual orientation, whether as a teacher, a judge, or a professional football player. My office worked with the National Football League last year to encourage a culture of inclusion and reinforce its policies barring discrimination based on sexual orientation against both current and prospective players.”

One result of the ongoing work is the policy below, which is posted in all 32 NFL locker rooms.

What would happen if a gay player like Sam thought teams were breaking the league’s policy (and state or local laws)? According to the NFLPA’s Atallah, the union could file a grievance with the league on behalf of the player. That could lead to arbitration and, eventually, some sort of penalty for the individuals or teams involved. If the player wanted to pursue the case in the courts, he could, provided that he was in one of the jurisdictions covered by a nondiscrimination law.

But wait: Is being drafted later (or not at all) because of sexual orientation equivalent to not getting hired? It depends. While draft position and player potential can be difficult to predict, a great deal of time and money goes into assessing NFL hopefuls’ skills before the draft, says Lambda Legal attorney Greg Nelson. “It is a noticeably different situation than most people applying for a job,” he explains. “If someone who is consistently viewed as being a third- or fourth-round draft choice and isn’t even drafted, then people would have a lot of explaining to do. Especially if their team gave up too many points last year.”

Nelson says that arguments against hiring a gay player for supposedly sports-related reasons—he’d be a distraction for the team; the fan base is too conservative to accept it—don’t hold water legally. He compares the situation to female job applicants being asked if and when they’re planning to have children; while it comes under the guise of planning for work, the question has nothing to with qualifications and everything to do with the applicant’s gender. “That is the definition of discrimination,” Nelson says.

So what about those anonymous comments from NFL and team bigwigs: Could they be actionable? If Sam could figure out who said them, and could then prove that that person or organization didn’t choose him because he’s gay, then yes. (An admittedly high bar.) Of course, predraft rumor mongering—often from nameless team execs, and about everything from players’ personal lives to injury histories—is as old as the draft itself. “The anonymous commentary revealed a stark contrast in the high integrity of Michael Sam opposed to their cowardice,” Atallah says. “Our league, just like the rest of society, has professionals of different backgrounds, faiths, values, and perspectives on different issues. But all of us have to adhere to certain basic principles of professionalism and nondiscrimination.”