An aerial view of the deadly mudslide in Washington. <a href="https://www.flickr.com/photos/wsdot/sets/72157642820245364/with/13387015254/">Washington State Department of Transportation</a>/Flickr

This story originally appeared on the Slate website and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

The death toll from this weekend’s mudslide through Oso, Wash., is still climbing, with more than 100 still listed as missing.

The stories emerging are the definition of heart-rending. Here’s one, from the Seattle Times:

One volunteer firefighter who had stopped working around 11:30 p.m. Saturday night said many tragic stories have yet to be told. He watched one rescuer find his own front door, but nothing else—not his home, his wife or his child.

They’re in the “missing” category along with many it is feared will eventually be listed as dead.

“It’s much worse than everyone’s been saying,” said the firefighter, who did not want to be named. “The slide is about a mile wide. Entire neighborhoods are just gone. When the slide hit the river, it was like a tsunami.”

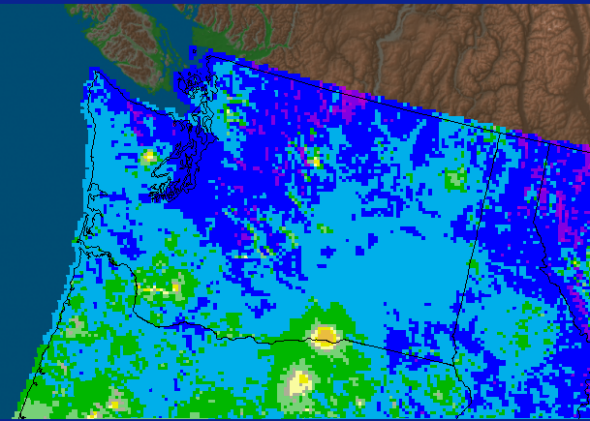

The most immediate cause of the mudslide is a near-record pace of rainfall for the area so far in the month of March.

The Pacific Northwest has had an exceptionally wet finish to its rainy season, as storms that historically would have hit California were re-routed northward by a semi-permanent dome of high pressure that’s been mostly responsible for the intensifying drought there.

This particular mudslide wasn’t just a freak event brought about by heavy rain, although this month’s deluge surely speeded the process. Another mudslide happened on this very same hillside just eight years ago.

In fact, the State of Washington recently completed a project aimed at preventing future mudslides, just short distance away from the site of this weekend’s deadly tragedy. Only problem is? It was on the other side of the river. Again, from the Seattle Times:

Sixteen months ago, the Washington State Department of Transportation (WSDOT) completed a $13.3 million project, called the Skaglund Hill Permanent Slide Repair, to secure an area just west of Saturday’s slide, on the opposite side of the Stillaguamish River.

That project covered about a half-mile stretch of Highway 530, from mile marker 36.25 to 36.67. It secured a hill south of the river. Saturday’s slide collapsed a hill north of the river and sent mud crashing into the Stillaguamish and across Highway 530 between mile markers 37 and 38, according to WSDOT.

This weekend’s tragedy reminds me of a similar pair of mudslides that occurred in 1995 and 2005 along the coast of California, in the tiny town of La Conchita. In 2005, heavy rains caused groundwater levels to rise, re-mobilizing the previous debris flow and creating a repeat tragedy.

Like in La Conchita, this weekend’s disaster occurred in an area known for its landslides. There are surely other, more remote areas where this process happens with less tragic results.

One of the most well-forecast and consequential components of human-caused climate change is the tendency for rainstorms to become more intense as the planet warms. As the effect becomes more pronounced, that will make follow-on events like flooding and landslides more common.

But we don’t have to wait for the future. This is already happening. Here’s an explainer, from the Union of Concerned Scientists:

As average global temperatures rise, the warmer atmosphere can also hold more moisture, about 4 percent more per degree Fahrenheit temperature increase. Thus, when storms occur there is more water vapor available in the atmosphere to fall as rain, snow or hail. Worldwide, water vapor over oceans has increased by about 4 percent since 1970 according to the 2007 U.N. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report, its most recent.

It only takes a small change in the amount of water vapor in the atmosphere to have a major effect. That’s because storms can draw upon water vapor from regions 10 to 25 times larger than the specific area where the rain or snow actually falls.

According to the U.S. Global Change Research Program’s (USGCRP) most recent report, scientists have observed less rain falling in light precipitation events and more rain falling in the heaviest precipitation events across the United States. From 1958 to 2007, the amount of rainfall in the heaviest 1 percent of storms increased 31 percent, on average, in the Midwest and 20 percent in the Southeast.

The United States Geological Survey maintains a database and monitoring program dedicated to identifying other places like La Conchita and Oso that may be at risk of future mudslides.