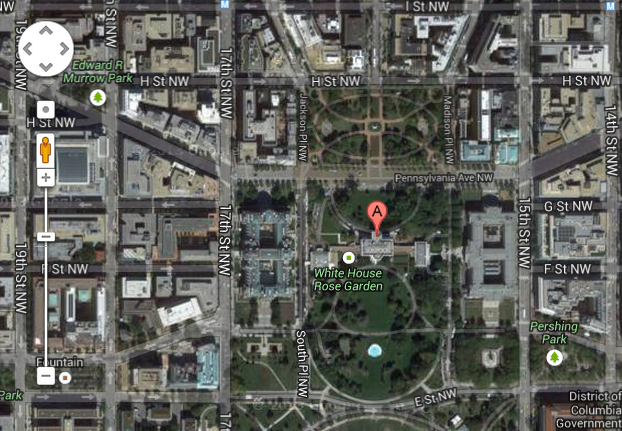

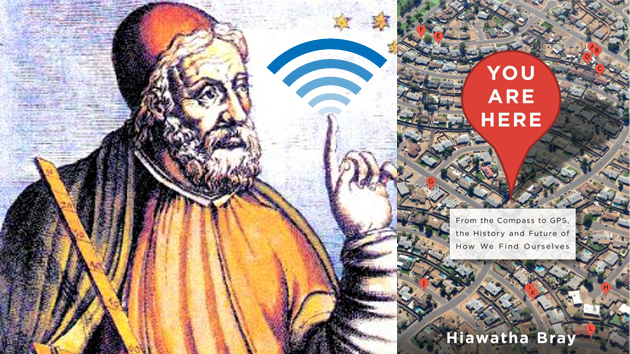

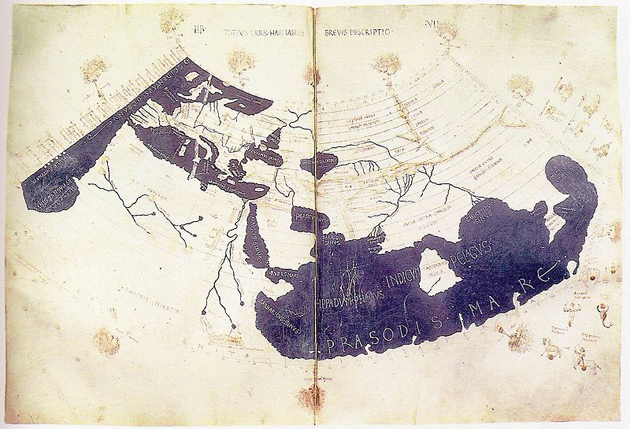

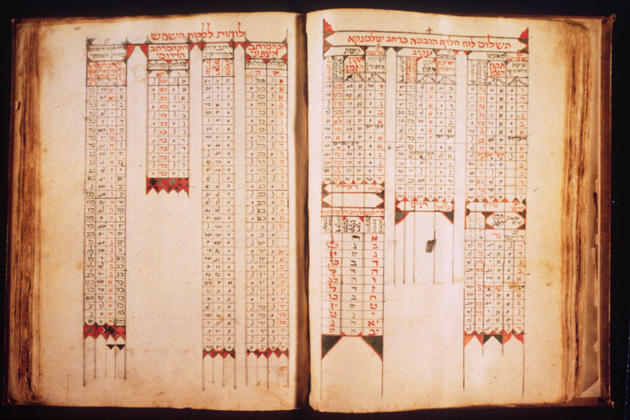

Egyptian geographer Claudius Ptolemy and Hiawatha Bray's "You Are Here"Basic Books; <a href="http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Ptolemaeus.jpg">Wikimedia Commons</a>; <a href="http://www.shutterstock.com/pic-170596721/stock-vector-phone-signal-on-white-background-vector.html?src=QurQExCLDP5CG1BmFvdFPw-1-0">Shutterstock/MeeKo</a>

Boston Globe technology writer Hiawatha Bray recalls the moment that inspired him to write his new book, You Are Here: From the Compass to GPS, the History and Future of How We Find Ourselves. “I got a phone around 2003 or so,” he says. “And when you turned the phone on—it was a Verizon dumb phone, it wasn’t anything fancy—it said, ‘GPS’. And I said, ‘GPS? There’s GPS in my phone?'” He asked around and discovered that yes, there was GPS in his phone, due to a 1994 FCC ruling. At the time, cellphone usage was increasing rapidly, but 911 and other emergency responders could only accurately track the location of land line callers. So the FCC decided that cellphone providers like Verizon must be able to give emergency responders a more accurate location of cellphone users calling 911. After discovering this, “It hit me,” Bray says. “We were about to enter a world in which…everybody had a cellphone, and that would also mean that we would know where everybody was. Somebody ought to write about that!”

So he began researching transformative events that lead to our new ability to navigate (almost) anywhere. In addition, he discovered the military-led GPS and government-led mapping technologies that helped create new digital industries. The result of his curiosity is You Are Here, an entertaining, detailed history of how we evolved from primitive navigation tools to our current state of instant digital mapping—and, of course, governments’ subsequent ability to track us. The book was finished prior to the recent disappearance of Malaysia Airlines flight 370, but Bray says gaps in navigation and communication like that are now “few and far between.”

Here are 13 pivotal moments in the history of GPS tracking and digital mapping that Bray points out in You Are Here:

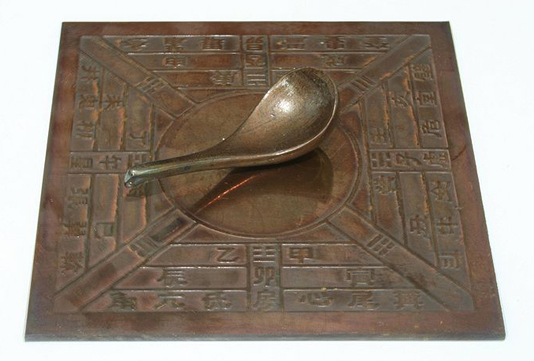

1st century: The Chinese begin writing about mysterious ladles made of lodestone. The ladle handles always point south when used during future-telling rituals. In the following centuries, lodestone’s magnetic abilities lead to the development of the first compasses.

2nd century: Ptolemy’s Geography is published and sets the standard for maps that use latitude and longitude.

1473: Abraham Zacuto begins working on solar declination tables. They take him five years, but once finished, the tables allow sailors to determine their latitude on any ocean.

1887: German physicist Heinrich Hertz creates electromagnetic waves, proof that electricity, magnetism, and light are related. His discovery inspires other inventors to experiment with radio and wireless transmissions.

1895: Italian inventor Guglielmo Marconi, one of those inventors inspired by Hertz’s experiment, attaches his radio transmitter antennae to the earth and sends telegraph messages miles away. Bray notes that there were many people before Marconi who had developed means of wireless communication. “Saying that Marconi invented the radio is like saying that Columbus discovered America,” he writes. But sending messages over long distances was Marconi’s great breakthrough.

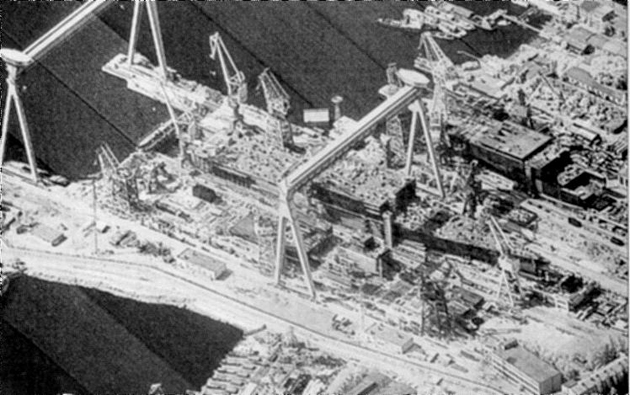

1958: Approximately six months after the Soviets launched Sputnik, Frank McLure, the research director at Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory, calls physicists William Guier and George Weiffenbach into his office. Guier and Weiffenbach used radio receivers to listen to Sputnik’s consistent electronic beeping and calculate the Soviet satellite’s location; McLure wants to know if the process could work in reverse, allowing a satellite to location their position on earth. The foundation for GPS tracking is born.

?1969: A pair of Bell Labs scientists named William Boyle and George Smith create a silicon chip that records light and coverts it into digital data. It is called a charge-coupled device, or CCD, and serves as the basis for digital photography used in spy and mapping satellites.

1976: The top-secret, school-bus-size KH-11 satellite is launched. It uses Boyle and Smith’s CCD technology to take the first digital spy photographs. Prior to this digital technology, actual film was used for making spy photographs. It was a risky and dangerous venture for pilots like Francis Gary Powers, who was shot down while flying a U-2 spy plane and taking film photographs over the Soviet Union in 1960.

1983: Korean Air Lines flight 007 is shot down after leaving Anchorage, Alaska, and veering into Soviet airspace. All 269 passengers are killed, including Georgia Democratic Rep. Larry McDonald. Two weeks after the attack, President Ronald Reagan directs the military’s GPS technology to be made available for civilian use so that similar tragedies would not be repeated. Bray notes, however, that GPS technology had always been intended to be made public eventually. Here’s Reagan’s address to the nation following the attack:

1989: The US Census Bureau releases (PDF) TIGER (Topologically Integrated Geographic Encoding and Referencing) into the public domain. The digital map data allows any individual or company to create virtual maps.

1994: The FCC declares that wireless carriers must find ways for emergency services to locate mobile 911 callers. Cellphone companies choose to use their cellphone towers to comply. However, entrepreneurs begin to see the potential for GPS-integrated phones, as well. Bray highlights SnapTrack, a company that figures out early on how to squeeze GPS systems into phones—and is purchased by Qualcomm in 2000 for $1 billion.

1996: GeoSystems launches an internet-based mapping service called MapQuest, which uses the Census Bureau’s public-domain mapping data. It attracts hundreds of thousands of users and is purchased by AOL four years later for $1.1 billion.

2004: Google buys Australian mapping startup Where 2 Technologies and American satellite photography company Keyhole for undisclosed amounts. The next year, they launch Google Maps, which is now the most-used mobile app in the world.

2012: The Supreme Court ruling in United States v. Jones (PDF) restricts police usage of GPS to track suspected criminals. Bray tells the story of Antoine Jones, who was convicted of dealing cocaine after police placed a GPS device on his wife’s Jeep to track his movements. The court’s decision in his case is unanimous: The GPS device had been placed without a valid search warrant. Despite the unanimous decision, just five justices signed off on the majority opinion. Others wanted further privacy protections in such cases—a mixed decision that leaves future battles for privacy open to interpretation.