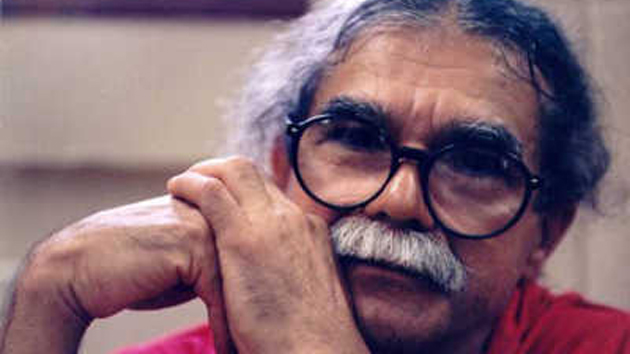

Courtesy of the <a href="http://peopleslawoffice.com/case-of-oscar-lopez-rivera/">People's Law Office</a>

From a prison in Indiana, a man writes his granddaughter: “After the family, what i miss most is the sea. Thirty-five years have passed since the last time i saw it. But i have painted it many times, the Atlantic part as well as the Caribbean, that smiling foam of light mixed with salt in Cabo Rojo. For any Puerto Rican, it is almost incomprehensible to live far from the sea.”

There are many people who want Oscar López Rivera to see the ocean again. He has served 33 years of a 75-year sentence for “seditious conspiracy” related to his participation in the FALN, a Puerto Rican nationalist group that claimed credit for a series of bombings in the 1970s and 1980s. (He was not charged with participating in any bombings, nor injuring anyone.) Nobel laureates Desmund Tutu and Mairead Maguire have called on President Obama to release him. So has the government of Puerto Rico, the American Association of Jurists, the AFL-CIO, the United Church of Christ, and the Movement of Non-Aligned Countries. Four members of Congress have called on President Obama to let him go. “Oscar has served 33 years in prison,” Rep. Gutiérrez emailed me. “He is being imprisoned for deeply held political views that resonate powerfully in the Puerto Rican community and beyond.”

López Rivera was convicted of conspiring against the US government as part of the FALN, a group that was fighting for the independence of Puerto Rico. The island had been a US possession since it was acquired from Spain in 1898. Puerto Ricans became US citizens in 1917—just two months before 20,000 of them were drafted to serve in World War I—but are not allowed to vote in the presidential elections or to have representation in the US Congress. In 1948, when López Rivera was five, the Puerto Rican legislature made it a crime to own a Puerto Rican flag, sing a patriotic song, or speak in favor of independence. The law was repealed in 1957.

At 14, López Rivera moved to Chicago. He fought in the Vietnam War, earning a Bronze Star; afterward, he worked to establish Illinois’s first Latino cultural center and organized to improve housing for Puerto Ricans in Chicago.

In 1981, López was charged with armed robbery, possession of an unregistered firearm, and interstate transportation of a stolen vehicle, allegedly as part of a larger plot to challenge the United States’ role in Puerto Rico by force. The court determined that he was connected to the FALN. At his trial, one man testified that López taught him bomb-making skills.

In all, the FALN claimed responsibility for more than 120 bombings across the US between 1974 and 1983, leading to the death of six and the injury of dozens. But the basis for López’s conviction was specifically the more than two-dozen bombings claimed by the organization in the Chicago area, none of which resulted in injuries. A 1980 Chicago Tribune editorial observed that the bombs were “placed and timed as to damage property rather than persons” and that the FALN was “out to call attention to their cause rather than to shed blood.”

At least 16 other Puerto Rican nationalists were charged with seditious conspiracy and related offenses in the early 1980s. None were ultimately found to have connections to actual attacks, yet at the sentencing hearing, the judge said he regretted not being able to issue the death penalty. He handed out sentences up to 90 years, with López Rivera receiving 55 years. By contrast, the average sentence for homicide in 1992 (the closest year for which data is available) was less than 12 and a half years.

During his 33 years in prison, López Rivera has served 12 years in solitary confinement in some of the highest security prisons in the country. His lawyer, Jan Susler says he hasn’t been allowed to do an in-person media interview for 15 years. Non-media visits are restricted as well, she says. A delegation that included a New York senator, a New York assemblyman, and New York City Council members were denied authorization to visit him in prison.

Today, few Puerto Ricans want independence from the United States—less than 3 percent, according to a 2012 referendum. Statehood is a much more popular goal. Still, Puerto Ricans across the political spectrum have called for López Rivera’s release. In November last year, at least 35,000 people marched in San Juan to call for a pardon. At the rally, an LGBT-rights leader publicly hugged an evangelical, anti-gay pastor inside a mock cell to symbolize their mutual support for López Rivera.

“There is a wide consensus, among different sectors of Puerto Rican society, that he should be released,” says Efren Rivera, a law professor at Puerto Rico University’s School of Law. “Most people here think his sentence is very disproportionate.”

President Bill Clinton apparently felt the same way. In 1999, against the protests of the FBI, the Federal Bureau of Prisons, the US attorney’s office, and even his wife, he offered clemency to López Rivera and 12 others convicted of seditious conspiracy. “These petitioners—while convicted of serious crimes—were not convicted of crimes involving the killing or maiming of any individuals,” Clinton said at the time. “The question, therefore, was whether the prisoners’ sentences were unduly severe and whether their continuing incarceration served any meaningful purpose.” Clinton noted that Puerto Rican independentista Jose Solis Jordan, convicted in 1999 of conspiring to bomb a Marine recruitment center, received a sentence of just 51 months.

Twelve of those whom Clinton offered clemency accepted. But López Rivera turned it down: He wouldn’t accept Clinton’s stipulation that he serve 10 years of a 15-year sentence he was given in 1987 for “conspiracy to escape.” He also noted that he couldn’t “abandon” his codefendant, Carlos Alberto Torres, who was not included in the clemency offer (though he, like López Rivera, was not accused of participating in bombings or of causing injuries). Torres was granted parole in 2010, but López Rivera has been denied it. Aside from one man serving a five-year sentence who will be released this year, López Rivera is America’s only remaining independentista prisoner.

His lawyer, Jan Susler, says he has applied for a commutation from President Obama. There is no widespread opposition to his release —the loudest voice has been conservative commentator Dick Morris—but the odds still seem stacked against López Rivera: Under Clinton, applicants for commutations had a 1 in 100 chance, while under Obama, the odds are 1 in 5,000. Still, there is precedent of presidents granting pardons just before leaving office: Bill Clinton pardoned 140 people on his final day. Harry Truman commuted the sentence of a Puerto Rican nationalist who had attempted to assassinate him. Jimmy Carter released four Puerto Ricans convicted of opening fire on members of Congress inside the US Capitol, saying that “no legitimate deterrent of correctional purpose is served by continuing their incarceration.”

López Rivera himself seems guardedly optimistic. Every Saturday, Puerto Rico’s main newspaper, El Nuevo Dia, publishes letters from López Rivera to his granddaughter. Last November, he wrote:

The future for me is something unpredictable…Puerto Rico has changed. So has the Chicago of my adolescence. Those nights when i stay awake thinking about my projects, i animate myself by telling myself that, at the end, i have survived 70 years and i have walked beneath the shadow of death many times. If a man has managed to survive this, how is he going to be afraid of the free air when it hits him in the face?