<a href="http://www.shutterstock.com/gallery-1466822p1.html">Aekkaphob</a>/Shutterstock

While pundits and vets argue over whether Bowe Bergdahl, the Army sergeant released from five years of captivity in Afghanistan by the Taliban in exchange for five Guantanamo Bay prisoners, is a hero or a traitor, one thing is clear: like Bergdahl, tens of thousands of soldiers have walked away from duty in the past two decades alone, and the Army has been puzzling over what to do with deserters for far longer. Here’s a primer:

What’s the difference between a deserter and someone who’s AWOL?

The terms “deserter” and “AWOL” are often used interchangeably, but in fact one condition precedes the other.

- AWOL: Any soldier who has taken unauthorized leave from their training or duty station

- Deserter: On 31st day of AWOL, a soldier is “dropped from the rolls” and administratively marked as a deserter

A good analogy between the two is the difference between cutting a class and dropping out of school altogether. It’s important to note that being administratively classified a deserter doesn’t necessarily mean a soldier has been convicted of desertion, which is a felony offense and involves a whole different process, usually involving an arrest and a court-martial. It just means the Army is marking you down as a deserter in its records, but may end up less-than-honorably discharging you rather than prosecute.

The military doesn’t have to wait the full 30 days to classify a missing soldier as a deserter, and therefore subject to court-martial, either. It just has to prove that the soldier left with no intention to return; after 30 days, the burden of proof is on the soldier to prove he or she did plan to return.

Any civil officer with the power to arrest can apprehend a deserter and deliver him or her into custody. As late as 2006, the Marine Corps was still hunting down and arresting Vietnam-era deserters.

So where does Bergdahl fall? He was captured within 24 hours of leaving his base without authorization. As the military news site Stars and Stripes makes clear, he was never classified as a deserter.

What happens to deserters?

When a soldier returns to the Army, whether voluntarily or after being apprehended, their commander has a number of options, including discharge, “retain and rehabilitate,” or prosecution through a court martial.

Prior to 2002, court martials for deserters were very rare. The vast majority of Army deserters—94 percent of the 17,000 who deserted between 1997 and 2001—were simply released from the Army with other-than-honorable discharges.

But beginning in 2003, army prosecutions of deserters increased sharply, in the face of growing numbers of soldiers dropping off the rolls rather show up for duty in Iraq and Afghanistan, with many receiving negative discharges or prison time.

For example, of the nearly 4,000 deserters counted in the fiscal year 2001, 4 percent were prosecuted. Just the year before, the number was just 1 percent.

In early 2002, the Army quietly issued a new directive pushing for the reintegration of deserters wherever possible, an order that didn’t go over well with Army officers. As one put it, “I can’t afford to babysit problem children everyday.”

Thanks to holes in the system, some deserters end up collecting money they didn’t earn. According to a report by the Government Accountability Office, between 2000 and 2002 the Army shelled out nearly $7 million to about 7,500 soldiers who had deserted or were otherwise absent without authorization.

How has the number of deserters changed over time?

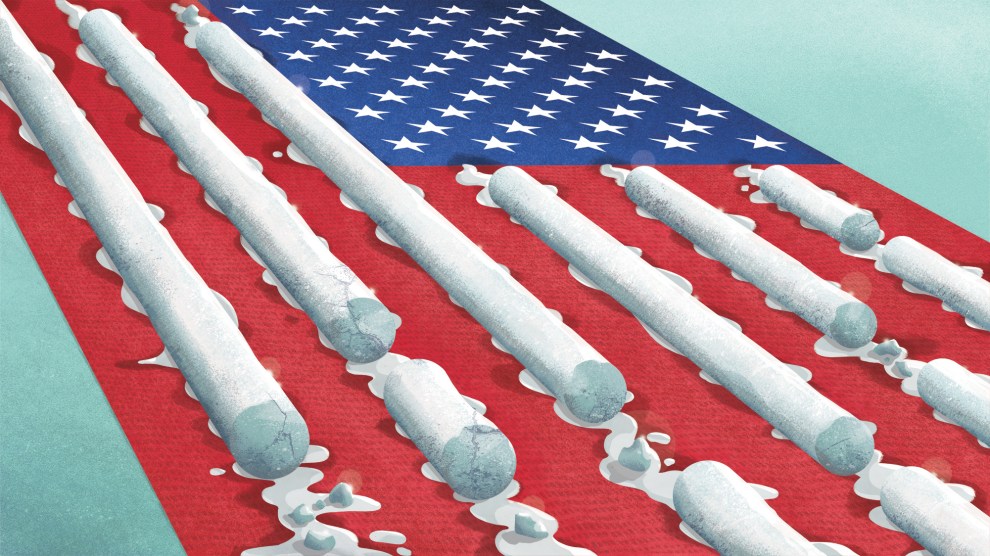

Desertion during the Vietnam War was chronic. Some 420,000 men across the armed forces were classified as deserters between the summer of 1966—the first year the US military began keeping official record of unauthorized absences—and late 1972. Between 1968 and 1971, the number of deserters as a percentage of the enlisted Army force averaged around 5 percent.

Post-Vietnam, the rate of desertions stayed below 1 percent until 2000. But desertions rose again during the Iraq and Afghanistan wars. Despite a dip immediately following the start of the war, by 2003, Army desertions were on an upswing that would persist for several years, until the economic downturn in 2008:

Data on Army deserters from earlier wars is patchier, but one estimate puts the number during World War II at 40,000 out of more than 16 million who served, putting the rate of desertion at well below 1 percent.

The dropout cycle

During wartime, as demand for soldiers increases, so does the rate of desertions. The Army typically drops its standards for enlistment during wartime, but it’s well known to Army researchers that enlistees who are in lower ranks, have less education, have pre-service delinquencies, and come from “broken homes” are also the ones most likely to desert.

Why do soldiers desert?

During the Iraq War, a Navy psychiatrist told the New York Times, combat stress was a major factor; at one Army base in Alaska in 2006, he said, “there was one guy who literally chopped off his trigger finger with an axe to prevent his deployment.”

A 2002 report by Army researchers said deserters are somewhat more likely to be in combat-related military occupational specialties. They also tend to have enlisted at young ages, come to the Army with less education behind them, and tend to leave before finishing their first full year in service.

Most try to work out their problems through the system before deciding to leave, by applying for hardship discharge or other administrative channels, and nearly half seek the help of someone in chain-of-command or an outside adviser like a chaplain. “Most soldiers do take steps to address their problems before leaving,” the report said.

The report also showed that family problems and “failure to adapt” were the most commonly cited reasons soldiers gave for desertion:

How much does it cost the Army when soldiers desert?

In 2002, the Army calculated that deserters who left before completing their first year of service in the calendar year 2000 cost the Army about $85 million, and would have to spend $38,000 to replace each fully trained member.