The Stay family and their five children. Both parents and four of the children were fatally shot Wednesday in their Texas home. Facebook/Harris County Sheriff's Office

On Wednesday evening, Ronald Lee Haskell, disguised as a FedEx delivery man, gained entry to the home of his sister-in-law and her spouse, Stephen and Katie Stay, demanding the whereabouts of his estranged ex-wife. According to statements by the Harris County police and prosecutors, he then allegedly tied up the Stays and their five children, ages 4 to 15, and shot them execution style, killing all but his 15-year-old niece, who played dead. Haskell then began driving to the home of the children’s grandparents, possibly to continue his rampage, but his critically injured niece managed to call 911. He was apprehended on the way by law enforcement. After a three-and-a-half-hour standoff three miles from the scene of the killings, Haskell surrendered and was arrested.

Court records show that in Utah in 2008, Haskell was charged with domestic violence and simple assault against his wife. She reported that he had hit her in the head and dragged her by the hair, according to police and court records. He pleaded guilty to the assault charge and had the domestic-violence charge dismissed as part of his plea deal. In July 2013, Haskell’s wife filed a protective order against him in Cache County, Utah, where they lived at the time. The order applied to her and their four children. She then moved away and filed for divorce about a month later. The divorce was finalized this past February.

It’s not yet clear if Haskell possessed his guns legally, but his case appears to be the latest example of how easy it remains for domestic abusers to possess firearms, thanks to weak legislation. Under federal law, Haskell’s protective order should have prohibited him from owning guns, says Laura Cutilletta, a staff attorney at the Law Center to Prevent Gun Violence. However, in October 2013, Haskell’s protective order was converted to a “mutual restraining order“ as part of their divorce and custody proceedings. (You can read the protective order docket, obtained by Mother Jones on Thursday, here.) This crucial step likely meant that Haskell was legally allowed to have guns again, under both state and federal law. Had the first protection order not been dropped, Cutilletta added, “likely he would have been prohibited.” Nor is it likely that Haskell’s 2008 conviction barred him from owning a gun in Utah or Texas, Cutilletta says, because he was convicted of simple assault rather than domestic violence. (Haskell’s attorney in his 2013 protective order proceedings did not respond to Mother Jones‘ request for comment.)

[Update July 11, 2:30 p.m. ET: As more documents on Haskell emerge, it appears that the mutual restraining order agreed to by him and his wife during their divorce proceedings could have qualified Haskell for the federal prohibition on possessing guns, Cutilletta says. But even then it may have done little to stop him, “because it was part of the divorce decree and not under the domestic abuse statute,” she says. “Therefore it likely wouldn’t have been reported to the FBI for the purpose of a background check.”

And there may have been another opportunity to disarm him: According to Chelsea Parsons, director of crime and firearms policy at the Center for American Progress, Haskell’s 2008 misdemeanor conviction for simple assault should have activated the federal bar on possessing guns. However, because Haskell entered a plea in abeyance to the crime, the assault conviction was dismissed after he’d committed no new crimes within eight months, keeping his right to possess guns intact.

Update July 12, 2:40 a.m. ET: New reporting shows that Haskell likely had two other pending restraining orders against him—one filed by his sister this past November, and the other by his mother as recently as July 3, 2014. Haskell’s mother told KHOU news that at her home in San Marcos, California, her son Ron got angry at her because she’d spoken to his ex-wife. He then “forcefully covered my mouth with his hand and pushed me inside the home,” duct-taped her to a chair, and then squeezed her neck trying to choke her to the point of unconsciousness. She said he claimed he was “going to kill me, my family, and any officer who stops him.” If this information proves accurate, it raises additional questions about the role of restraining orders in this case, and whether they should have triggered a federal- or state-level ban on gun ownership.]

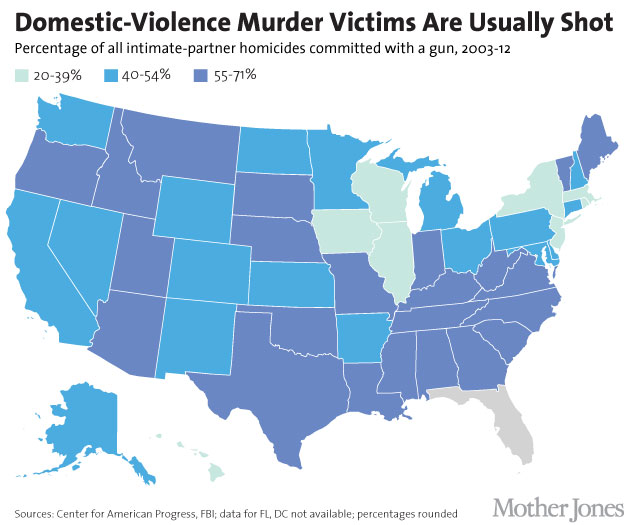

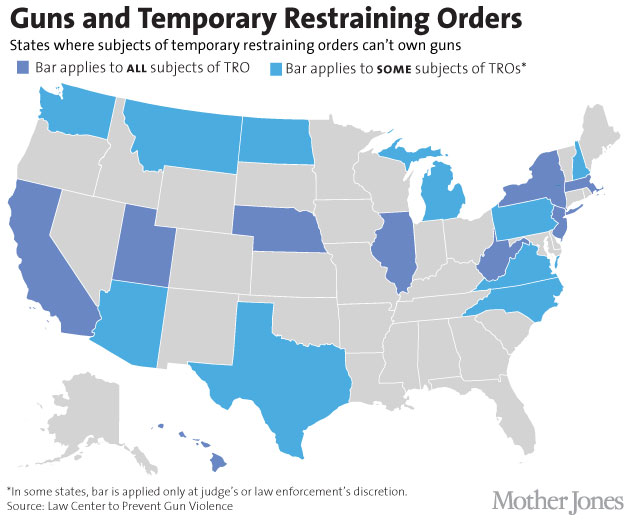

Three different bills that would strengthen federal law are currently stalled in Congress, in part due to lobbying efforts of gun rights groups, including the National Rifle Association. Federal law prohibits convicted felons, subjects of permanent domestic-violence protective orders, as well as current and former spouses, parents, and guardians who have been convicted of domestic-violence misdemeanors from possessing a gun. But this leaves many situations where potential abusers are allowed to keep their guns. The current law doesn’t apply to misdemeanant stalkers, domestic-violence misdemeanants who are current or former dating partners but who’ve never cohabitated or had a child together, as well as accused partners subject to a temporary (rather than permanent) restraining order. This is concerning, especially considering that in more than half of all states, fatal violence between intimate partners is most often perpetrated with a firearm. (See map above.)

In June, US Sen. Richard Blumenthal (D-Conn.) cited the case of 32-year-old mother Lori Gellatly when introducing a bill that would bar Americans served with temporary restraining orders for domestic violence from purchasing or possessing a firearm. In April 2014, a court granted Gellatly a temporary restraining order against her husband after she fled their home and filed for a permanent protective order, citing her husband’s violent behavior toward her and their twins. But thanks to the holes in federal law, he was allowed to keep his guns until a judge issued a permanent restraining order. Gellatly’s husband allegedly shot her with a legally owned gun one day before she was set to argue her case.

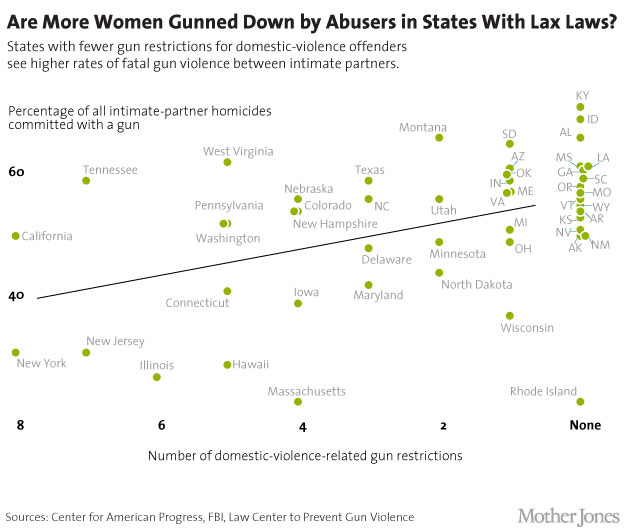

Data suggests that states with fewer measures to keep guns out of the hands of domestic abusers see more guns used in intimate-partner murders: (For our methodology, see the bottom of this post.*)

A different bill, though, does: Proposed last July by Sen. Amy Klobuchar (D-Minn.), the Protecting Domestic Violence and Stalking Victims Act would extend existing federal provisions to those convicted of stalking offenses and to abusive dating partners, but it doesn’t address the question of temporary restraining orders. Blumenthal’s bill, along with several others, have taken a piecemeal approach to bolstering federal law. In addition to its provision on temporary restraining orders, Blumenthal’s bill would also extend existing domestic-violence provisions to dating partners. However, this bill doesn’t address gun ownership by convicted stalkers.

A third bill, reintroduced last month by Rep. Lois Capps (D-Calif.), is a combo platter of the Blumenthal and Klobuchar bills, aiming to fill all three holes in the current federal law—protecting victims from dating partners, convicted stalkers, and accused partners subject to temporary protective orders while they await a more permanent court ruling.

These efforts have irked pro-gun groups. The NRA sent a letter to senators in June saying that Klobuchar’s bill “manipulates emotionally compelling issues such as ‘domestic violence’ and ‘stalking’ simply to cast as wide a net as possible for firearm prohibitions.”

For now, the gun lobby has little to worry about: These legislative solutions haven’t moved far in Congress, with Klobuchar’s bill sitting in committee for the past year. At the state level, protections aren’t much better:

Guns and stalking: A review of conviction records in 20 states by the Center for American Progress showed that there are at least 11,986 people in the United States who’ve been convicted of misdemeanor level stalking but are still permitted to possess a gun: Federal law doesn’t prohibit it, and neither do their states’ rules.

Almost all states have felony stalking laws on the books, which automatically preclude the convicted from owning guns. Misdemeanor-level stalking crimes, usually punishable by a year or less in jail, exist in 42 states. Some, like the NRA, argue that nonfelony stalking isn’t serious enough to warrant a gun ban. However, research has repeatedly shown that stalking is often a precursor for more violent behavior: A 1999 study by the New York Department of Health, for example, found that 76 percent of women murdered by an intimate partner were stalked beforehand. Only 11 states and the District of Columbia prohibit misdemeanant stalkers from owning guns:

Guns and temporary restraining orders: Temporary restraining orders can be awarded ex parte—meaning the accused isn’t present. Final protective orders, on the other hand, require both parties to present their case in court. This is part of why the gun lobby regularly tries to block legislation barring gun possession by those subject to TROs. Such laws, pro-gun groups argue, could cause an individual to lose his right to own guns without a chance to make his case.

In a 2008 study, about 11 percent of women killed in an intimate-partner homicide had a protective order against their assailant. The federal bills proposed are important because, as of yet, just nine states entirely prohibit anyone subject to a TRO from owning guns. A few other states enact this prohibition at a judge’s or law enforcement’s discretion, or some other type of qualification.

But even a nontemporary protective order won’t always do the trick of keeping guns out of the hands of domestic-violence perpetrators: When a final protective order or a misdemeanor domestic-violence conviction are handed down, the ensuing bar on guns is technically permanent. However, some states have a “relief from disability” process by which perpetrators can apply to reinstate their permission to own guns.

Guns and dating partners: Although the marriage rate in the United States declined to a historic low last year, federal law still relies on an antiquated definition of relationships when determining whether alleged domestic abusers should surrender their weapons. People convicted of a domestic-violence offense against partners that they’ve never been married to, cohabitated with, or had a child with are not banned from possessing guns.

This is worrying, especially because dating partners, not spouses, comprise a growing proportion of perpetrators of domestic violence: Between 2003 and 2012, more nonfatal violence was committed against women by a current or former dating partner than a current or former spouse—39 versus 25 percent. And while 69 percent of intimate-partner homicides were committed by a spouse in 1980, compared to 27 percent by dating partners, by 2008 those rates had flipped: 49 percent of intimate-partner homicides were committed by a dating partner, compared to 47 percent by a spouse.

Yet even as dating partners account for almost half of intimate-partner homicides, only nine states and the District of Columbia have instituted a ban on gun possession for dating partners:

This patchwork of weak laws endangers women, the data shows: Their chances of being killed by their abusers increase more than five times if he has access to a gun.

Scatterplot methodology: We looked at eight kinds of laws that restrict people accused of domestic violence from possessing guns, using data provided by the Center for American Progress and the Law Center to Prevent Gun Violence. We included laws that bar possession for misdemeanor offenders convicted of various domestic violence crimes, as well as laws addressing permanent and temporary protective orders and the removal of firearms from the convicted. We then counted how many of these kinds of protections each state had before 2013 and compared that number to the percentage of intimate-partner homicides committed with a gun from 2003 through 2012, as reported by the FBI.

Adam Winkler, a law professor at the University of California-Los Angeles, notes that there are a number of other variables that could affect this data, like education levels, income, and unemployment rates of perpetrators. We also did not have access to a breakdown of how many of these homicides were committed with illegally—versus legally—obtained guns. Still, Winkler says that the correlation does “make a point and raise questions.”

For more of Mother Jones‘ award-winning reporting on guns in America, see all of our latest coverage here, and our special reports.