Astrid Riecken/ZUMA

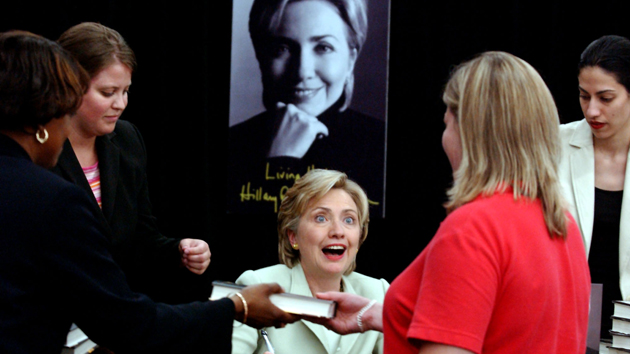

Adam Parkhomenko had just spent a week tailing Hillary Clinton, following her halfway around the country in a Winnebago emblazoned with a now iconic photo of the former secretary of state wearing shades and texting, when I ran into him outside an auditorium on George Washington University’s campus last month. Parkhomenko—a baby-faced 28-year-old, wearing a pink button down and baseball cap—blended in amidst the millennial-heavy crowd of die-hard Hillary fans outside the event, where Clinton had just spoken about her new book. Yet Parkhomenko was an outlier. The executive director and cofounder of Ready for Hillary super-PAC—part of a trio of groups encouraging Clinton to run for president in 2016 alongside Correct the Record and Priorities USA—Parkhomenko had remained outside the theater during the entire event, skipping the chance to hear Hillary speak. As Parkhomenko—a campaign aide during Hillary Clinton’s last presidential bid—proudly told me that evening, he hasn’t seen or spoken with Hillary since 2008.

In fact, Ready for Hillary’s staff has scrupulously avoided attending any of her book tour speeches. The group has enacted what Allida Black, the group’s other cofounder, terms a “kryptonite firewall between the PAC and the candidate.” Ready for Hillary’s communications director, Seth Bringman, notes: “With her direct staff or family there is no coordination or communication. Being an independent group that’s always something made clear to everyone and it’s also commonsense.”

But it turns out these politicos don’t have to fully separate themselves from the Clinton machine. In the Wild West of post-Citizens United campaign finance law, there is a major loophole that would allow Clinton to work as closely as she likes with any of the super-PACs that are working to boost her 2016 chances. The same goes for any candidate who, like Clinton, does not hold political office and is not a declared candidate.

Super-PACs sprang up in the wake of the Supreme Court’s 2010 decision on Citizens United and other rulings that weakened campaign finance law. Unlike regular PACs that can only take in contributions up to $5,000 and give money directly to candidates, super-PACs are free to raise unlimited amounts of cash from big-dollar donors—as long they reveal the names of donors and refrain from dealing directly with the candidates they support. They have to make what are known as “independent expenditures” on behalf of (or against) a candidate without coordinating with a candidates’ campaign. Super-PACs allow wealth donors much more opportunity to shape a race.

The Federal Election Commission has been lax on enforcing a strict definition of coordination between a super-PAC and declared candidates. Politicians and their aides are free to speak at fundraisers for super-PACs supporting them—as Obama staffers and Mitt Romney did during the 2012 election—provided they confine themselves to requesting donations under the $5,000 contribution limit that applies to non-super-PACs. Yet once the politician or campaign aide has left the room, super-PACs are free to ask high-dollar donors for unlimited checks. “The FEC’s view of coordination is not a common sense view of coordination,” says Larry Noble, former general counsel at the FEC. “The FEC allows things that most would look at and say ‘that’s clearly coordinated.'”

A new study by Daniel Tokaji and Renata Strause at Ohio State University examines what happens behind the scenes with campaign staff, super-PACers, and politicians; it notes that there are already numerous ways campaigns and super-PACs collude. “At the end of the day,” one anonymous campaign operative told them, “it’s all just kind of a fiction—it’s just kind of a farce, the whole campaign finance noncoordination thing.”

But the situation is worse—or looser—when a super-PAC is assisting someone who is still making up his or her mind about whether to wage a campaign. “How can you issue judgment on whether super-PACs are coordinating with a candidate, when there’s not a candidate?” says Lee Drutman, a senior fellow at the Sunlight Foundation. “There’s nothing, to my knowledge, that prevents [the potential candidate and the super-PAC] from getting together and strategizing and sharing understandings and whatnot.” A politician who has not yet declared his candidacy could help a super-PAC round up million-dollar donations to help his future campaign and dodge limits that will apply to contributions made after he officially enters the race.

Despite a book tour that is operating as a proto-presidential campaign, Clinton isn’t officially running for president, still claiming that she’s making up her mind. “She’s not a candidate right now,” Noble says, “so if they did coordinate with her right now it wouldn’t really matter.”

Clinton isn’t likely to delay her presidential decision in order to preserve her ability to work with these super-PACs. The moment she declares her candidacy, she will be inundated with campaign cash. But this loophole could cause down-ballot candidates-to-be to postpone making their bids for office official. These political hopefuls could rake in unlimited funds for a super-PAC and set its strategy for the remainder of campaign season.

“There’s every reason, under these rules, for a candidate to wait until the last possible minute to declare their candidacy, if they have a super-PAC or other outside group that’s effectively raising money for their campaign,” Drutman says. Some candidates have already started to test the edges of acceptable behavior. Ryan Zinke, a GOPer running for Montana’s sole US House seat, founded and managed an anti-Obama super-PAC and then quit last year. Shortly thereafter, the super-PAC began pushing a “draft Zinke” message. It declared its support for candidate Zinke when he announced his congressional bid a month later.

Ready for Hillary isn’t alone among the pro-Clinton super-PACs in proceeding with a heightened level of caution not necessarily required by the law. “We simply don’t coordinate with Secretary Clinton or her staff,” says Adrienne Elrod, communications director of Correct the Record, another pro-Clinton super-PAC. “We make our own decisions beginning with the decision not to coordinate.”

Bringman insists that none of Ready for Hillary’s paid staff communicate with Clinton’s office, but he couldn’t offer the same guarantee for the group’s outside advisers, who include many Clinton vets with close ties to Hillaryland. Correct the Record is staffed by veterans of Clinton’s last presidential campaign who remain friendly with people in Clinton’s immediate circle. But these political ops say their conversation with their old pals don’t cover the work of the PAC.

Clinton herself has obviously been tracking the super-PACs’ work. Earlier this month the New York Times reported that she called to thank Chicago Mayor Rahm Emanuel after he endorsed her for 2016 and gave his support to Ready for Hillary. Bill Clinton has kept tabs on Ready for Hillary by talking to friends aligned with the group.

Clinton’s camp has publicly distanced itself from these groups of supporters. “While they are an independent entity acting on their own, their enthusiasm is flattering,” Nick Merrill, a Clinton spokesman has told reporters. But Merrill did not respond to a request for comment regarding whether Hillary the private citizen is doing anything to preserve any wall between her shadow campaign and the operatives already at work for her (possible) presidential bid.