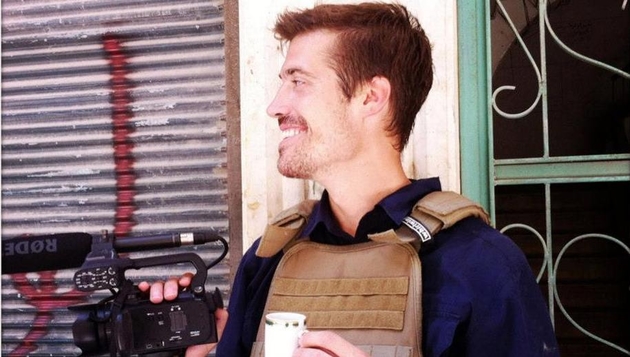

Photo by Nicole Tung

When I first saw the image of James Foley kneeling before a masked Islamic State member gripping a knife, I wanted to look away, forget, and go for a walk outside. I know the dragging uncertainty of living years and months in the power of someone who sees you as a lever against their enemy. I have a hint of the hot, tingling numbness one feels realizing this could be one’s last hour alive.

People who have lived through hostage situations know who the survivors are. We don’t like to think about the ones who didn’t make it while we are here, alive, free and moving on.

People who once were in these situations are almost always connected in some way to those who are in them now. I never knew James, but I’d been asked to weigh in on his case more than once. This happens with some regularity: Americans seem to be kidnapped more and more around the world, used as leverage against the US government. When someone like James goes missing, people scramble to do something—anything—they think will help. Many will have the sensible idea to contact others who have been in a similar situation. At the time, people thought James was being held by the Syrian government, and people thought a statement from myself, Sarah Shourd, and Josh Fattal—held as hostages by the Iranian government for two years—might grab the attention of someone in a position to put pressure on his captors.

I declined these requests, because I was afraid it could hurt rather than help; after all, Josh and I were convicted of espionage by Assad’s allies in Iran.

James’ family has had to endure many calculations like these. Like my family, they probably sometimes thought they should do more to try and convince his captors to let him go. Other times they likely reasoned they should stay quiet, hoping that silence would give the hostage takers the opportunity to quietly release him. It’s a hideous position to be in.

James was kidnapped twice. The first time was in Libya, in 2011. Two weeks after he was released, he told an interviewer, “If reporters, if we don’t try to get really close to what these guys—men, women, Americans—and now, with this Arab revolution, young Arab men—are experiencing, we don’t understand the world, essentially.” This is true. Without people like James on the ground, it is impossible to understand what is happening in places like Syria. And without understanding, how do we decide what to do (or not to do)?

James went to Syria to report on the most deadly war in the world. More than 9 million people have been driven out of their homes. The country is also the most dangerous place to be a journalist—at least 66 have been killed there since 2010. Most of these were Syrian. Countless journalists are still missing. In the video claiming to show James being beheaded, ISIS showed another kidnapped American journalist, Stephen Sotloff. It warned that he, too, would be executed if the United States did not end its intervention in Iraq.

After the video of his execution was released, James’ parents posted a comment on Facebook: “We have never been prouder of our son Jim. He gave his life trying to expose the world to the suffering of the Syrian people.” Like the deaths of more than 100,000 Syrians, it’s hard to find anything in James’ death but tragedy. But in life he was braver than most of us, and committed to something much bigger than himself. That’s what I want to remember.