<a href="http://www.thinkstockphotos.com/image/stock-photo-prison-hands/118657761">Dan Bannister</a>/Thinkstock

We still don’t know definitively what made a Ferguson, Missouri, police officer shoot and kill an unarmed black teen in broad daylight this past weekend. What we do know is that minorities in the United States—particularly black men—are over-represented in their interactions with the criminal justice system: African Americans make up less than 14 percent of the nation’s population, but 40 percent of the prison population.

Yet highlighting these disparities may actually hurt blacks more than help them, according to a study published last week in Psychological Science. The Stanford University researchers, Rebecca Hetey and Jennifer Eberhardt, conducted two experiments that showed how making white people aware of the high numbers of blacks in prison actually made them more likely to pursue harsher punishments. Here is a rundown of their experiments:

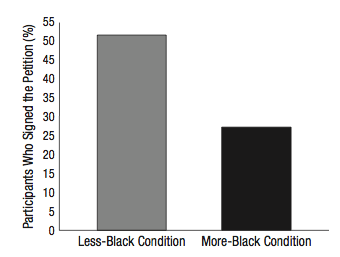

Experiment 1. White Californians were shown videos in which mugshots of black and white prisoners flashed on the screen, two per second. Half of the subjects saw a video containing 25 percent black photos (the “less-black condition”) while the other half saw a video with 45 percent black photos (the “more-black condition”). Each participant was then given a chance to sign a petition proposing an amendment to relax California’s “Three Strikes” law, which stipulated that anyone with two serious or violent felonies on their record would get a 25-year-to-life sentence for any third offense, even if it was stealing a dollar in loose change from a parked car—true story. (According to the Justice Policy Institute, African Americans were given life sentences under Three Strikes at nearly 13 times the rate of whites. The real-life amendment, which passed in November 2012, called for the harsh sentencing only if the third strike was also a violent or serious felony.) Just over half of the participants in the less-black scenario signed the leniency petition, but only 27 percent of those who watched the more-black video were willing to sign.

Three-strikes leniency. From Hetey and Eberhardt, “Racial Disparities in Incarceration Increase Acceptance of Punitive Policies,” Psychological Science, 2014

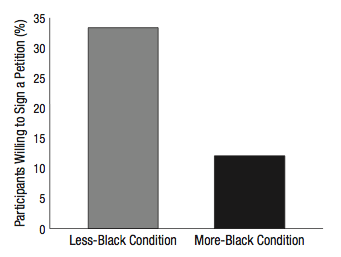

Experiment 2. White subjects in New York City were informed of the city’s stop-and-frisk program, through which hundreds of thousands of people each year are frisked for weapons, resulting in few arrests but an abundance of racial profiling. They were then presented with one of two true statistics: That blacks comprise 40 percent of America’s prison population (“less-black condition”) or that blacks made up 60 percent of New York City’s prison population (“more-black”). The subjects given the more-black statistic were far less likely to sign a petition to curb the stop-and-frisk program: Just 12 percent signed, compared to about one-third of the subjects who got the less-black stat. The researchers suggest that the racial preconditioning they induced may have evoked a greater fear of crime among the participants. (They specifically recruited white participants for the study; whether blacks and other ethnic groups would respond similarly is an open question.)

Opposition to stop-and-frisk. Hetey and Eberhardt, “Racial Disparities in Incarceration Increase Acceptance of Punitive Policies,” Psychological Science, 2014

What makes these experiments interesting is that they look beyond racial profiling by cops on the street to touch on the racism of ordinary citizens making decisions in a safe setting. In research from a decade earlier, one of the study’s authors pointed out that not only do people more often associate blacks with violent crime, but that “simply thinking of crime can lead perceivers to conjure up images of Black Americans.”

The upshot is that reminding white people of racial disparities in the prison population led them to favor policies that contribute to those very disparities. So what to do? The researchers write:

Many legal advocates and social activists assume that bombarding the public with images and statistics documenting the plight of minorities will motivate people to fight inequality. Our results call this assumption into question . . . This produces quite a challenge for those striving to create a more equal and just society. Perhaps motivating the public to work toward an equal society requires something more than the evidence of inequality itself.

What that “something more” is, they don’t say.