Abbas Dulleh/AP

With the Ebola virus continuing its spread throughout West Africa—and landing this week in a fifth country, Senegal—the custodians of global health are becoming more adamant that the world is not doing enough to stop the deadly pathogen. That is, the rich nations of the world are not providing sufficient resources for the fight against Ebola. World Health Organization leaders came to Washington last week to ask for $600 million to build and administer new treatment centers in Liberia, Guinea, and Sierra Leone—the three countries with the most infections—and provide safe burials for victims in those countries. This is essential, given that the killer virus spreads via bodily fluids, and many people have contracted the disease through contact with the bodies of dead Ebola victims.

Due to budget constraints, the WHO had only a limited presence in West Africa at the time of the outbreak and it failed to detect and contain the virus before it got out of control. These poor countries had to deal with the crisis on their own during the epidemic’s earliest stages. The WHO’s earlier budget cuts also caused the organization to lose some of the senior staff most qualified to lead a response.

So why was the WHO caught flat-footed? One reason: International governmental support for the WHO has leveled off in recent years, failing to keep up with rising needs. Most of the WHO’s budget is funded by contributions from member states—about 80 percent of its 2011 budget came from annual dues and voluntary donations from governments. The remainder is financed by donations from large foundations and organizations, such as Rotary International and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.

According to a report by the Congressional Research Service, US funding for global health programs increased steadily until 2011, when it declined for the first time. In 2010, US support for the WHO’s general fund totaled $280 million, according to WHO documents; two years later, Washington had reduced its contribution 23 percent, to $215 million.

The drop in US support was part of an overall global trend. As the long-term effects of the financial crisis set in, many member states replaced stimulus packages with austerity budgets and cut back on their commitments to the WHO. In 2010, the WHO’s proposed budget greatly exceeded the money coming in. Faced with reduced income in 2011, the WHO scaled back its budget for 2012-13 to around $3.96 billion total, about 20 percent less than what its leaders originally wanted. The organization also slashed 300 jobs at its Swiss headquarters. In 2013, the US again significantly reduced its contribution, dropping its funding to $180 million.

The 2014-15 budget, approved in May 2013, held steady at about $3.97 billion. That budget also halved funding for handling health crises to $228 million. Moreover, about two-thirds of the WHO’s overall budget is earmarked by donors, including the United States, for certain projects, such as anti-Malaria or HIV/AIDS programs. Consequently, a substantial portion of the organization’s funds are off-limits for the Ebola effort.

On August 28, the WHO released a plan to stop Ebola; the price tag was $490 million, with most of the funds dedicated building treatment centers, hiring more staff, and providing safe burials for victims in Sierra Leone, Liberia, and Guinea—the three countries with the most infections. But as the outbreak has progressed, the proposed budget for the WHO’s anti-Ebola campaign has increased. When WHO officials met with officials from the State Department, the Food and Drug Administration, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, they requested help to fill a $600 million gap.

On September 4, the United States Agency for International Development pledged $100 million to help the effort, adding to more than $21 million the agency already committed for protective gear and food intended for Liberia, Guinea, and Sierra Leone. But making use of the new support will be a slow process. “This will take weeks and we are expecting the situation will get worse before it gets better,” USAID administrator Rajiv Shah told the Wall Street Journal. On September 5, the White House sent a letter to Congress requesting $30 million for the CDC’s Ebola effort, to pay for additional staff in the United States and in Africa. The allocation would be part of the spending bill that the House is expected to vote on Thursday.

“This is going to be a test of the national capacity of these countries,” UN Deputy Secretary-General Jan Eliasson said at a press conference on September 2. “But it’s also going to be a test of multilateralism; a test of international solidarity for people in dire need right now.”

The statistics about the current Ebola outbreak have become more alarming in recent days. More than 3,000 people have been infected and more than 1,900 have died. Forty percent of the cases have occurred in the last three weeks. On August 28, the WHO announced that as many as 20,000 could be infected, and 10,000 killed before the current outbreak would be brought under control.

“There is a window of opportunity to tamp this down,” said CDC director Tom Frieden at a recent press conference. “But that window is closing.”

“Leaders are failing to come to grips with this transnational threat,” Joanne Liu, international president for Doctors Without Borders, told the United Nations.

“In a way, we feel saddened by the response,” President Ellen Johnson Sirleaf of Liberia said this week of the international efforts to curb Ebola in her country.

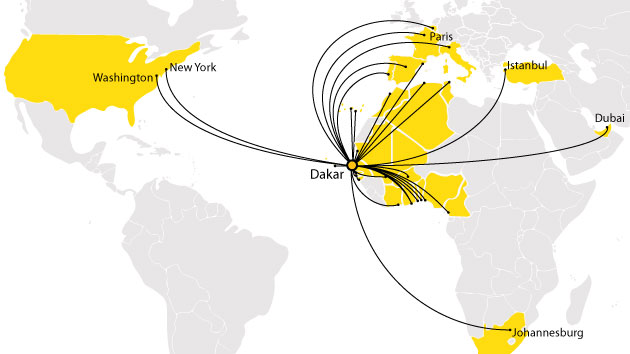

On Wednesday, the WHO declared Ebola’s spread to Senegal a “top priority emergency” and confirmed a new outbreak in Port Harcourt, Nigeria, noting this burst of the disease has the potential to “grow larger and spread faster” than the previous outbreak in Nigeria.

At a congressional hearing on August 7, Ken Isaacs, vice president of government relations for Samaritans Purse, a Christian relief organization, called on the United States to respond. “The international response to the disease has been a failure,” he said. If the world did not respond with a coordinated intervention, “the world will be effectively relegating the containment of this disease that threatens Africa and other countries to three of the poorest nations in the world.”

The death toll since that hearing has nearly doubled.