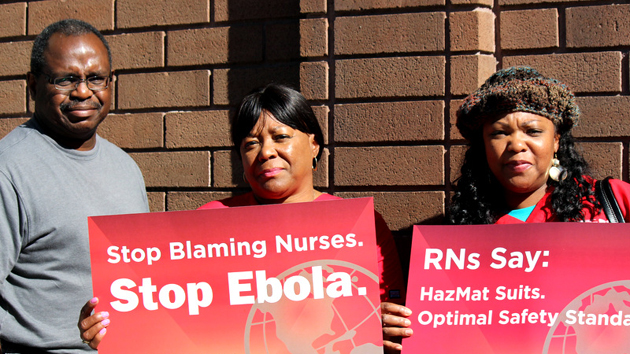

Nurses rallying in Oakland, CaliforniaGabrielle Canon

More than 200 nurses rallied outside the National Nurses United headquarters in Oakland, California, on Tuesday, demanding more stringent protections from Ebola for health care workers. They carried signs reading “Stop Blaming Nurses. Stop Ebola.” and wore red stickers declaring “I am Nina Pham” and “I am Amber Vinson”—the names of the two nurses who contracted Ebola from Thomas Eric Duncan, the only person to have died from Ebola on American soil. (A fourth patient, a New York City doctor, was diagnosed yesterday.)

The rally was one of many held around the country this week, organized by the NNU to press President Obama and lawmakers to mandate stronger protections for nurses and other health care workers treating Ebola patients. The NNU alleges that Pham and Vincent were exposed to the virus due to the lack of safety protocols at their hospital in Texas. In a survey conducted by the union, four out of five nurses reported they have not been instructed how to properly handle Ebola patients.

While there was plenty of talk at the rally about the need to implement the recently issued recommendations from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, no one mentioned the federal rules concerning Ebola that are already on the books—and how they could be better publicized and enforced.

The Occupational Safety and Health Administration has long-standing regulations on protecting workers from infectious diseases, including Ebola. Introduced in 1986, OSHA’s Bloodborne Pathogen Standard is intended to keep health care workers from contracting HIV as well as hepatitis C, malaria, syphilis, and viral hemorrhagic fevers (like Ebola). The standard requires hospitals to provide and require the use of protective equipment such as masks and face shields to ensure that “blood or other potentially infectious materials” do not touch workers’ clothes, skin, face, or mucous membranes.

Juliann Sum, the acting chief of Cal/OSHA, California’s occupational safety division, says these rules exceed the recommendations currently being demanded by the nurses’ union. “What was in place and what is still in place now are regulations,” Sum says. “The Bloodborne Pathogens Standard has been in place for over 30 years around the whole country.”

OSHA also has specific requirements for respiratory protections from bioaerosols (airborne particles that could contain viruses) and a standard for personal protective equipment. These rules apply to anyone who might come into contact with an infectious disease on the job, including airline flight crews, lab workers, customs agents, and morticians. “All viruses are covered, including the flu,” Sum says.

So why are nurses and health care workers saying they haven’t been properly protected from Ebola? Part of the answer, explains Rena Steinzor, a professor at the University of Maryland School of Law who has written about workplace safety, is that OSHA has suffered from budget cuts and a lack of political support for decades. “You could reel it back to Reagan,” Steinzor says. “There were cuts and a downward trend and eventually it got to the point where they never recouped it.” Already underfunded, the agency was hit hard by sequestration. In the last four years, the agency’s budget (in real dollars) fell by 10 percent, though it rose slightly in the last fiscal year.

OSHA is responsible for overseeing 8 million workplaces and 130 million workers. With a workforce of about 2,200 inspectors, that’s about one inspector for every 59,000 workers. Federal and state OSHA inspectors inspected 0.5 percent of workplaces in the 2013 fiscal year, a rate that remained fairly constant over the previous seven years.

America’s hospitals see around 250,000 work-related injuries and illnesses every year. Even though OSHA has identified hospitals as “one of the most hazardous place(s) to work,” its health care inspections have declined significantly. Of the roughly 39,000 workplace inspections done last year, 254 were of hospitals. That’s down from 374 the previous year and 559 where they peaked in 2009.

When hospitals are inspected, close to 75 percent of violations given cite the Bloodborne Pathogens Standard*. It is the most common citation received by employers in the health care industry. “When you don’t inspect places, compliance becomes lax because nobody is concerned about it,” Steinzor explains.

Those statistics provide some context for the nation’s initial response to Ebola, particularly in Dallas, where Duncan was treated. A statement from the NNU details numerous alleged breaches of protocol during his stay at Texas Presbyterian Hospital. “Nurses had to interact with Mr. Duncan with whatever protective equipment was available, at a time when he had copious amounts of diarrhea and vomiting which produces a lot of contagious fluids,” it states. If that’s accurate, Texas Presbyterian was in violation of OSHA rules.

When it does uncover workplace safety violations, OSHA can’t do much more than slap offenders on the wrist. More than 4,400 workers are killed on the job each year. Yet the maximum fine for serious violations is $7,000, and criminal penalties for negligence resulting in workers’ deaths may not exceed misdemeanors with six-month prison terms. As David Michaels, the assistant secretary of labor for OSHA, noted in a 2011 speech, there are harsher consequences for harassing burros on federal land or violating the South Pacific Tuna Act.

Considering this, perhaps hospitals and health care workers can’t be blamed for not realizing that OSHA already has rules regarding Ebola in place. At NNU headquarters in Oakland, union copresident Debra Burger emphasized that her organization wants new rules for dealing with the virus. She said she has no faith in hospitals stepping up to the plate voluntarily. “The gaping hole in protection is that guidelines from the CDC are just that,” she said. “They are suggestions. Employers get to pick and choose which parts of the CDC requirements are implemented, and so we have grave concerns.” When asked about the OSHA standards already in place, she shrugged. “I can’t speak to that,” she responded.

Meanwhile, on the other side of the door, Cal/OSHA representatives were preparing to meet with nurses and other health agencies to plan a course of action. It’s not yet clear if that means new regulations or simply a new push to enforce existing ones.

One healthy result of the Ebola scare, says Cal/OSHA head Sum, is the renewed attention on protections for health care workers. “I think the silver lining here,” she says, “is that if this crisis can get everyone more prepared, then we will be prepared when there is another wave of possible threat of another kind of infection.”

Correction: The original version of this article stated that 75 percent of hospitals violate the Bloodborne Pathogens Standard. It has been corrected to reflect that when cited, 75 percent of citations given are for breaking the standard.