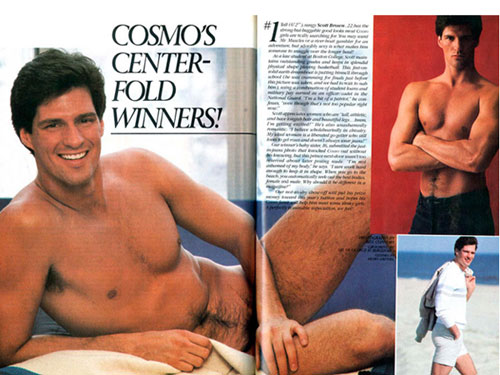

Harry Hamburg/AP

Name a major super-PAC or dark-money outfit and there’s a good chance it has helped Republican Scott Brown, the former senator from Massachusetts now trying to oust Democratic Sen. Jeanne Shaheen of New Hampshire. Karl Rove’s American Crossroads? Check. The Koch-backed Americans for Prosperity? Check. The US Chamber of Commerce, billionaire Joe Ricketts’ Ending Spending, FreedomWorks for America, ex-Bush ambassador John Bolton’s super-PAC—check, check, check, and check.

Despite being a darling of conservative deep-pocketed groups, Brown once was a foe of big-money machers. As a state legislator in Massachusetts, he sought to curb the influence of donors by stumping for so-called clean elections, in which candidates receive public funds for their campaigns and eschew round-the-clock fundraising. But during his three years in Washington—from his surprise special-election win in January 2010 to his defeat at the hands of Elizabeth Warren in November 2012—Brown transformed into an insider who embraced super-PACs, oligarch-donors such as the Koch brothers, and secret campaign spending. On the issue of money in politics, there is perhaps no Senate candidate this year who has flip-flopped as dramatically as Brown. Here’s how it happened.

In November 1998, Brown won a seat in the Massachusetts House. That same year, voters in the state approved a ballot measure to implement a clean elections system; the proposal passed by a 2-1 margin. By law, however, ballot measures can’t allocate taxpayer funds, and the fight to implement the new system moved to the legislature in Boston.

Brown allied himself with supporters of clean elections. As part of the state House’s tiny Republican caucus, Brown clashed with the old-guard Democratic leadership, including House Speaker Tom Finneran, who viewed clean elections as inimical to incumbents. Brown did quibble with reformers over some details of the proposed clean-elections system, but he voted in 2002 against a plan that would have gutted the program.

David Donnelly, who spearheaded the clean elections effort in Massachusetts, remembers Brown as a reliable supporter of clean elections: “Over those years, Scott Brown was not only a consistent vote, but a consistently outspoken supporter of the clean-elections program.” In a June 2001 letter to the editor in the Boston Globe, an activist with Common Cause, the good government group, hailed Brown’s support for clean elections as “not only courageous, but gutsy and heroic.”

When Brown ran for state Senate in 2004, he billed himself as “the person that bucks the system often.” He frequently mentioned his support for clean elections as evidence of his reformer bona fides. “As a state representative,” he said then, “I fought House Speaker Thomas Finneran’s pay raise bill and supported the voters’ will on Clean Elections.” Brown won the special election and served in the state Senate from 2004 to 2010.

In 2010, Brown ran for the US Senate seat that had been held by Ted Kennedy for 46 years. Most people remember his ubiquitous pickup truck, the one he drove everywhere and used to burnish his regular-guy image. What’s less remembered is how Brown again bragged about his support of campaign finance reform on his way to becoming a US senator.

Here’s what Brown told NPR the day after his upset win over Democrat Martha Coakley:

Maybe there’s a new breed of Republican coming to Washington. You know, I’ve always been that way. I always—I mean, you remember, I supported clean elections. I’m a self-imposed term limits person. I believe very, very strongly that we are there to serve the people.

That reformer approach vanished as soon as Brown joined the Senate Republican caucus.

In the summer of 2010, Senate Democrats heavily lobbied Brown to be the decisive 60th vote on the DISCLOSE Act, a bill that would beef up disclosure of spending on elections by dark-money nonprofit groups, including Karl Rove’s Crossroads GPS and David Koch’s Americans for Prosperity. But Brown instead joined the Republican filibuster that killed the bill. In an op-ed explaining his vote, Brown said the bill was an election year ploy that exempted labor unions, which traditionally back Democrats, from some disclosure requirements. (In fact, the bill applied the same requirements to corporations and unions, and the AFL-CIO opposed it.) But he praised the 2002 McCain-Feingold campaign finance reform law as “an honest attempt to reform campaign finance” and wrote that genuine reform “would include increased transparency, accountability, and would provide a level playing field to everyone.” This gave some reformers hope that Brown might support a whittled-down version of the bill.

But no. Brown later opposed two newer, slimmer versions of the DISCLOSE Act and refused to cosponsor a national clean-elections bill similar to the measure he had backed in Massachusetts. (A spokeswoman for Brown’s campaign did not respond to a request for comment.)

Brown has gone on to accept millions from the interests most opposed to campaign finance reform. In 2011, he was caught on camera practically begging David Koch, the billionaire industrialist, for campaign cash. “Your support during the [2010] election, it meant a ton,” Brown told Koch. “It made a difference, and I can certainly use it again.” In his 2012 race against Warren, he benefited from a super-PAC funded largely by energy magnate Bill Koch, the youngest Koch brother and also a billionaire, and casino tycoon Sheldon Adelson’s Las Vegas Sands company. And though he agreed that year to the “People’s Pledge”—a pact intended to keep outside spending out of the campaign—Brown refused to make the same pledge in his current campaign against Shaheen.

As a state legislator, Brown bragged that he was someone who “bucks the system often.” Today, he is relying on the system—dominated by millionaires and billionaires, overrun with money, and cloaked in secrecy—to get back to the Senate.