<a href="http://flickr.com/link-to-source-image">Peter Gudella</a>/Shutterstock

Michelle Flores thought she had everything worked out for Thanksgiving. The 20-year-old San Francisco State junior was planning to join friends this Thursday to make pineapple-crusted ham, a family favorite. But last Friday, the Safeway where Flores works as a part-time cashier informed her that she’d be expected to work during on the holiday. She reluctantly called her friends to cancel their Thanksgiving plans.

Flores is well acquainted with the stressful unpredictability of part-time work. Last semester, she found out just three days before her midterm exams that the supermarket expected her to work 30 hours that week, 25 percent more than what she typically put in. One night, she got off work at 9, made it home by 10, and had to study all night for a 9 a.m. exam. “I definitely would have done better if I’d had more sleep,” she says. “Had I been notified sooner I could have studied more beforehand.”

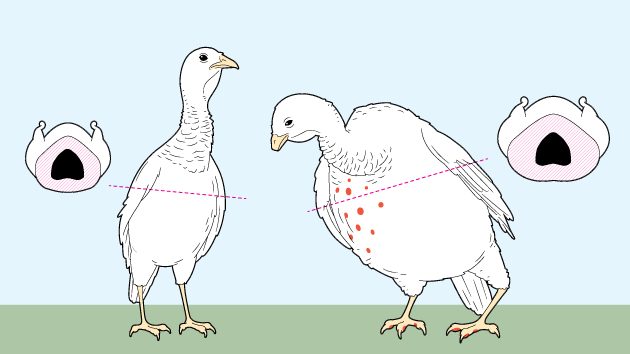

For millions of retail workers, similar disappointments are all too common. According to a recent study by Susan Lambert, a professor at the University of Chicago School of Social Service Administration, nearly half of young part-time retail employees receive their work schedules less than a week in advance. This is partly a symptom of retailers’ increasing reliance on computerized “on call” scheduling systems that track weather predictions and real-time sales data to schedule work shifts—maximizing efficiency but wreaking havoc on workers’ ability to manage their personal schedules.

But for Flores and 40,000 other retail workers in San Francisco, that’s about to change. Yesterday, San Francisco’s Board of Supervisors passed two laws that will sharply curtail “on call” scheduling at the city’s major chain stores.

“We see this as one exciting way to address the inequality gap and pull low-wage workers out of poverty,” says Gordon Mar, the executive director of Jobs With Justice San Francisco, a coalition of community and labor groups that has lobbied for the measures for more than a year. He sees them as important complements to San Francisco’s new $15 minimum wage. While the wage is highest in the country, it still “isn’t enough on its own to really create security for low-wage workers that are struggling to survive,” says Mar.

The bills, known as the Retail Workers Bill of Rights, will make sweeping changes to how large service-industry employers hire, schedule, and retain their workforce. The new rules require employers to post worker schedules at least two weeks in advance. They discourage arbitrary or inconvenient “on call” shifts by requiring employers to pay workers when the shifts are canceled at the last minute, which can happen when real-time sales slow down. Employers are essentially banned from relying entirely on part-time workers, a common strategy to avoid paying benefits; they must now offer available shifts to existing employees before hiring new ones. And they must offer part-time workers the same opportunities for promotions, raises, and time off as full-time employees.

“It’s really exciting to see San Francisco break ground on solutions for low-wage workers,” says Carrie Gleason, the director of the Center for Popular Democracy’s Fair Workweek Initiative. “The workweek has changed a lot in recent years, but the last time we legislated workplace standards on these issues was 75 years ago. It’s long overdue that we set new standards.”

More than five years into the recovery, the economy has added middle-class jobs much more slowly than part-time service positions such as cashiers and fast-food clerks. Consequently, since 2007, the number of part-time workers who’d like to work full-time positions has doubled. As Jodi Kantor reported in a gripping New York Times profile of a Starbucks barista, the shift towards part-time work and “on call” scheduling has had the effect of “injecting turbulence into parents’ routines and personal relationships, undermining efforts to expand preschool access, driving some mothers out of the work force and redistributing some of the uncertainty of doing business from corporations to families.”

Several states, including California and New York, already have “reporting pay” laws that require employers to pay workers extra if they send them home early from a shift. Last year, SeaTac, an airport town between Seattle and Tacoma in Washington, became the first in the country to require employers to offer additional hours to part-time workers before hiring new employees. But San Francisco’s Worker Bill of Rights goes much further than these efforts, and labor organizers expect it to help catalyze similar worker rights laws elsewhere.

Jobs for Justice, the group that lobbied for the San Francisco bills, is pushing similar measures in the Washington, DC, and Boston. Minnesota and New York are considering tighter regulations of “on call” shifts. Those two states and Michigan may also adopt laws that would bar employers from discriminating against part-time workers who request more stable schedules. The Service Employees International Union is pushing for a mandatory 30-hour workweek for security and janitorial workers in multiple states.

The Schedules That Work Act, introduced in this July in Congress by Reps. George Miller (D-Calif.) and Rosa DeLauro (D-Conn.), mirrors many of the provisions of the Retail Workers Bill of Rights, including advance notice for shifts and pay for workers sent home early. Labor groups don’t expect the bill or a companion measure in the Senate to pass, but see them as rallying points for other state and local legislation.

The new San Francisco laws go into effect seven months after the mayor signs them and apply to chain stores with more than 20 employees and 20 global locations. For Flores, the changes come as a relief, albeit not soon enough to salvage her Turkey Day. The current system “does deteriorate your quality of life,” she says. “It’s more convenient for them, without considering what is a better option for you.”