<a href="https://www.flickr.com/photos/rogersmith/8149299155">Roger Smith</a>/Flickr; Creatas Images/Thinkstock

When Democrats in Congress tried to fix the financial system in 2010, one of their main goals was to end the plague of giant financial institutions that had attained too-big-to-fail status—gargantuan banks and non-banks (say, insurance companies) that could one day collapse and, consequently, sink the entire economy unless they received a government bailout. The Dodd-Frank Wall Street reform legislation that Congress passed compelled financial regulators to identify these companies and called for extra rules for these behemoths to minimize the risk of implosion.

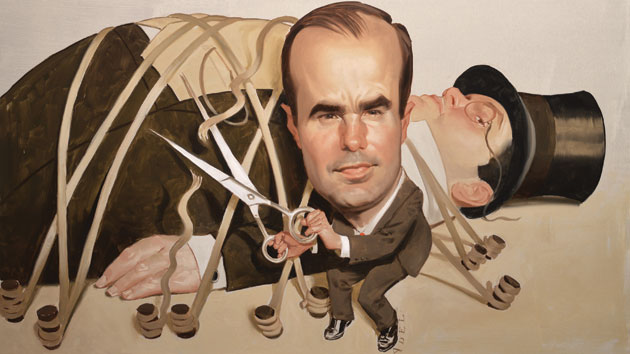

So far that process has been humming along relatively smoothly. But it could soon be derailed in court, thanks to Eugene Scalia, the son of Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia and a partner at the Washington power-law firm Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher. In recent years, Scalia the Younger, on behalf of the Chamber of Commerce and other clients, has waged a campaign via a series of lawsuits to defang assorted Dodd-Frank rules governing banks and other financial institutions. Scalia’s lawsuits have largely aimed at marginal aspects of financial reform, not the foundational elements of the Wall Street reform law. But Reuters reported earlier this month that insurance giant MetLife—preferred insurer of Snoopy—had hired Scalia, an indication the firm was preparing to take the government to court to challenge a designation that MetLife is a too-big-to-fail institution. If such a case does ensue and Scalia is successful, he could make it tough for the government to label any non-bank as too big to fail.

Dodd-Frank established the Financial Stability Oversight Council (FSOC), a 10-member body of government regulators, including the secretary of the Treasury and the chair of the Federal Reserve. This council is in charge of determining which financial companies qualify as a Systemically Important Financial Institution, or SIFI. Under Dodd-Frank, the process for designating a bank a SIFI is straightforward: any bank with $50 billion in assets is automatically a SIFI. Nineteen US banks now meet this definition.

But deciding which non-banks pose a systemic risk is trickier. To slap the SIFI label on a non-bank, the FSOC has to consider 11 factors, including how much leverage the company carries, whether it is a major player in handing out loans to US businesses, how interconnected it is with institutions already designated as SIFIs, and the level of credit it provides to low-income and minority communities.

Once declared a SIFI, a bank comes under the supervision of the Federal Reserve and is subject to stricter rules, such as higher capital requirements. But for the non-banks deemed SIFI, the Federal Reserve has yet to issue new rules, leaving unclear what extra requirements they will be forced to comply with as too-big-to-fail institutions.

So far, the FSOC has said just three non-bank companies are too big to go under: AIG, Prudential, and GE Capital. In September, the FSOC unanimously proposed listing MetLife—the largest insurer in the country—as a SIFI, a move that the company immediately challenged. In early November, according to Bloomberg, Scalia and MetLife’s CEO met with the FSOC to argue against the designation. The board still must issue a final declaration on MetLife, but given the earlier consensus, it seems likely it will stick to the original decision.

MetLife’s recourse would be to contest the designation in court. It’s not certain that MetLife would sue the FSOC. As The Wall Street Journal reported, “The people familiar with the matter said a major factor in MetLife’s decision about litigation would be the strength of the written rationale provided to the company by the Financial Stability Oversight Council.” But it appears a good bet that Scalia would find room to object. The pioneering tactic he has used to convince judges to reject other financial regulations is to argue that the government didn’t conduct a thorough cost-benefit analysis before issuing a regulatory decision—that is, contending that the feds were lazy with their math and didn’t provide enough justification for the way they devised a rule. And when the FSOC has issued SIFI designations in the past, its rulings have tended to be more thematic and analytical than facts-drenched. The public decision on Prudential, for example, runs 12 pages and broadly discusses the insurance company’s role in the economy without presenting many statistics to back up the claim that Prudential poses a wider risk if there’s a run on its assets. (FSOC also provides Prudential and other SIFIs with a longer, confidential document that includes specific facts and figures).*

In May, Scalia testified before the House Committee on Financial Services and slammed the FSOC’s decision on Prudential. “The process by which companies are considered for designation is exceptionally opaque,” he griped in his written testimony, describing this particular decision as lacking “substantiation and analytic rigor.”

Scalia has had a good run, winning a series of cases challenging other parts of Dodd-Frank. But several of those victories came at the DC Circuit Court of Appeals, which until recently was dominated by Republican appointees. Now, thanks to the Democrats’ decision to weaken the Senate filibuster, the appeals court has several new Obama appointees, shifting the balance of power to a majority that might be less hostile to the FSOC’s decision-making. So as MetLife ponders whether to mount a legal crusade against the financial regulators, its officials have to consider this: with those new judges, can Scalia continue his streak? And should they bring and a case and lose, what are the odds a higher court featuring another Scalia—who might have to recuse himself—could help them out?

*This article has been updated.