Matt Chase

On March 4, the Supreme Court will hear oral arguments in King v. Burwell, a lawsuit designed by conservative advocates to destroy Obamacare. If the plaintiffs prevail, about 8 million people could lose their health insurance. Premiums are likely to skyrocket by 35 percent or more, threatening coverage for millions of others. Health policy experts have estimated that nearly 10,000 people a year could die prematurely if they lose their coverage. Obamacare itself could collapse.

The King case started out as a legal theory hatched by a group of conservative lawyers in 2010 at a conference sponsored by the American Enterprise Institute, the right-leaning think tank. Attendees were urged to devise a litigation strategy to bring down the Affordable Care Act, which months earlier had been signed into law. The libertarian Competitive Enterprise Institute, a think tank funded by big pharmaceutical firms, oil and gas outfits, the Koch brothers, Google, tobacco companies, and conservative foundations, answered the call. (“This bastard has to be killed as a matter of political hygiene,” Michael Greve, then CEI chairman, said at the conference.) But CEI had to recruit plaintiffs—actual people who could claim they had been harmed by the Affordable Care Act in a particular way—to launch its lawsuit.

So who are the two men and two women that CEI handpicked to front its assault on Obamacare? What harm had they suffered as a result of the health care law? And why are they willing to put their names on a suit that could jeopardize the health coverage of millions of fellow Americans?

I set out to track down the plaintiffs to hear in their own words why they had decided to take part in the case, and it soon became evident that CEI had struggled to find suitable candidates. Three of the four plaintiffs are nearly eligible for Medicare, meaning their objections to Obamacare will soon be moot. Two of them appear to qualify for hardship exemptions—that is, they are not forced to acquire insurance or pay fines because even with a subsidy insurance would eat up too much of their incomes—so it’s unclear how Obamacare had burdened them. These two plaintiffs seemed driven by their political opposition to President Obama; one has called him the “anti-Christ” and said he won election by getting “his Muslim people to vote for him.” Yet most curious of all, one of the plaintiffs did not recall exactly how she’d been recruited for the case and seemed unaware of the possible consequences if she wins. Told that millions could lose their health coverage if the Supreme Court rules in her favor, she said that she didn’t want this to happen.

The case is legally complex. It centers on the claim that the Internal Revenue Service has illegally interpreted the Affordable Care Act to provide subsidies to people who live in states that have not established online health insurance exchanges and use the federal exchange to obtain insurance. The lawsuit asserts that Congress intended for Americans to receive insurance subsidies only through state exchanges—an argument that the bill’s congressional drafters have vehemently denied. In a complicated legal maneuver, the plaintiffs argue that if the IRS hadn’t illegally made subsidies available to them, they would have the right to the hardship exemption provided by the law that would free them from paying a fine for going uninsured. (Exemptions are available to Americans whose health insurance costs would be more than 8 percent of their incomes.)

At its core, this convoluted case is an ideological vehicle driven by well-funded conservative interest groups bent on demolishing Obamacare. But it wouldn’t exist without these four average Americans CEI signed up as plaintiffs. Public interest litigation, as this case purports to be, generally has some obvious benefits for plaintiffs. But this case is different. For the King plaintiffs a victory will mean they will end up with the right either to pay more for their health coverage or to go uninsured—and Americans receiving subsidized insurance in 34 states could lose their premium subsidies and, likely, their insurance coverage

Meet the people behind the case:

Brenda Levy

Levy, 64, lives outside of Richmond. She will qualify for Medicare in June, around the same time the Supreme Court is likely to issue a decision in this case. A substitute teacher with wild, frizzy gray hair and earthy clothes—she lives in a house that resembles a log cabin—Levy looks like an aging hippie. When I met her in January, she mentioned that she’d once belonged to the Sierra Club and that she used to read Mother Jones. She seemed an unusual candidate for a libertarian-tinged lawsuit designed to eviscerate Obamacare.

What was more surprising, though, was that she said she didn’t recall exactly how she had been selected as a plaintiff in the case to begin with. “I don’t know how I got on this case. I haven’t done a single thing legally. I’m gonna have to ask them how they found me,” she told me. She thought lawyers involved with the case may have contacted her at some point and she had decided to “help ’em out.”

How did they track her down? I asked if she was involved in GOP or conservative politics. Was she a tea party member who had registered her opposition to Obamacare on a petition or at a rally? Levy insisted she leads “a quiet life.” But she is politically active. A prolific writer of letters to the editor denouncing gay rights activists, Levy was also a donor to California’s anti-gay-marriage ballot amendment Proposition 8. In 2013, she helped to organize a rally outside the headquarters of the local Boy Scouts council in Richmond to protest the organization’s plan to consider allowing gay kids to join (which eventually was adopted). You can see her here:

Levy has yet to attend any of the court proceedings in King v. Burwell, because she “didn’t think the case was going anywhere.” At the time we spoke, Levy said that she had never met the lawyers handling the case in person, despite the fact that it had been pending for more than a year. But she said she planned to travel to Washington for the Supreme Court oral arguments in March: “It’s an adventure. Like going to Paris!”

When I asked her if she realized that her lawsuit could potentially wipe out health coverage for millions, she looked befuddled. “I don’t want things to be more difficult for people,” she said. “I don’t like the idea of throwing people off their health insurance.”

Levy was under the impression that if the case prevailed, someone would surely fix the insurance situation, probably at the local level. “I think [Virginia’s Democratic Gov.] Terry McAuliffe wants to expand Medicaid,” she remarked. She didn’t know that the Medicaid expansion was part of Obamacare, or that the same forces backing her lawsuit have opposed this expansion in her state. She was also unaware that there is no Plan B in the works to rescue the people who could lose their insurance if her case is successful.

Still, she’s no fan of Obamacare. She claimed it gives the government control over Americans’ medical treatment and that the law has spurred the IRS to expand. And she said she doesn’t like the idea of young people subsidizing her insurance. Levy contended that Obamacare had caused many Americans to lose their insurance and for premiums to rise.

In fact, the percentage of uninsured Americans has fallen from 18 percent to 13.4 percent since the law took effect last year. And Obamacare has made health care more affordable than ever before. This especially holds true for Levy. She told me she faced monthly health care premiums of $1,500, which she attributed to health woes that have included two craniotomies and two hip replacements. “I’ve had some holes drilled in my head,” she quipped. Levy hasn’t checked out the plans she qualifies for under Obamacare, but a October 2013 affidavit filed by the government in King v. Burwell indicates that at that time she could have purchased a low-cost bronze plan on the federal exchange for $148 a month. Given this, it’s unclear how Obamacare has caused her any real harm.

David King

The lead plaintiff in the case, King is a burly Vietnam vet whose large frame filled the doorway of his modest Fredericksburg, Virginia, home when I knocked on his door in January. The mustachioed 64-year-old wore a dark suit and was preparing for his gig later that day as a self-employed limo driver. When I asked him about the lawsuit, he brought up Benghazi. He despises Obama (“He’s a joke!”), and loathes the president’s signature achievement. His Facebook page features posts slamming the president (“the idiot in the White House”) and Obamacare.

According to legal filings in his case, he’s married and a smoker. When the lawsuit was filed in September 2013, King’s projected 2014 income was $39,000, entitling him to a premium subsidy for health insurance that would allow him to purchase a bronze plan for $275 a month—a price that would be lower if he didn’t smoke. (The ACA allows insurance companies to charge smokers up to 50 percent more for premiums.) Without the subsidy, the same plan would cost $648 a month. King wouldn’t say whether he’s currently covered, but he was adamant that he would never utilize Obamacare, no matter what.

But King isn’t compelled to use Obamacare. Because the cost of his subsidized premium would be more than 8 percent of his income, he should qualify for a hardship exemption. Obamacare doesn’t require him to buy insurance or force him to pay a penalty if he decides to forgo it. So as with Levy, it’s not clear what real harm he is seeking to remedy.

I asked King what he got out of the case. He replied that the only benefit he would receive from the case was the satisfaction of smashing Obamacare, which he believes bilks hardworking taxpayers to support welfare recipients. He said he doesn’t care if millions of Americans lose their health coverage, because “they’re probably not paying for it anyway.”

But according to a new analysis by the Urban Institute, of the 8 million people most at risk of losing their health insurance if King prevails, 80 percent are employed. Moreover, 70 percent are high school graduates or have some college education, more than 60 percent are white and live in the South, and 82 percent of them are not poor but low- and middle-income. More than a million of the Americans whose health coverage this lawsuit puts at risk are over 55. In short, many of them are David King.

Unlike most of the people who could suffer if his lawsuit succeeds, King may soon have his insurance problems relieved by a different government health care plan. He’ll be eligible for Medicare in October.

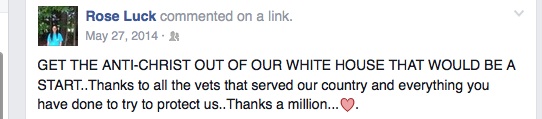

Rose Luck

I wasn’t able to knock on Luck’s door because the home address she provided in legal filings turned out to be a $200-a-week extended-stay motel on a commercial strip in Petersburg, Virginia, a last refuge for people who’ve fallen on hard times. She had long since moved on by the time I tried to contact her there. In 2012, the bank foreclosed on the house Luck and her husband had purchased only a year earlier. Luck hung up on me when I finally reached her by phone. Contacted via Facebook with a detailed list of questions, she responded, “Please leave me alone.”

But public records provide a snapshot of her life and hardships. Since the late 1990s, legal judgments have been entered against her and her husband in Virginia courts for nearly $5,000 in unpaid medical bills (they have since been paid off). Such judgments are the hallmark of people who lack insurance or who are underinsured.

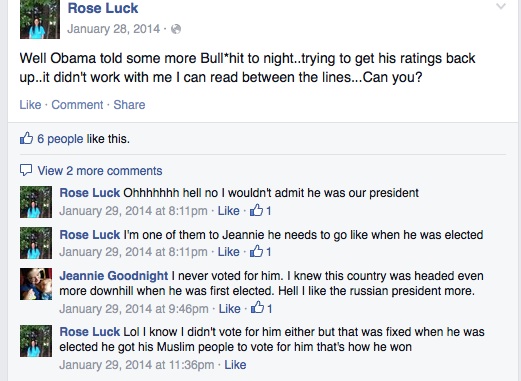

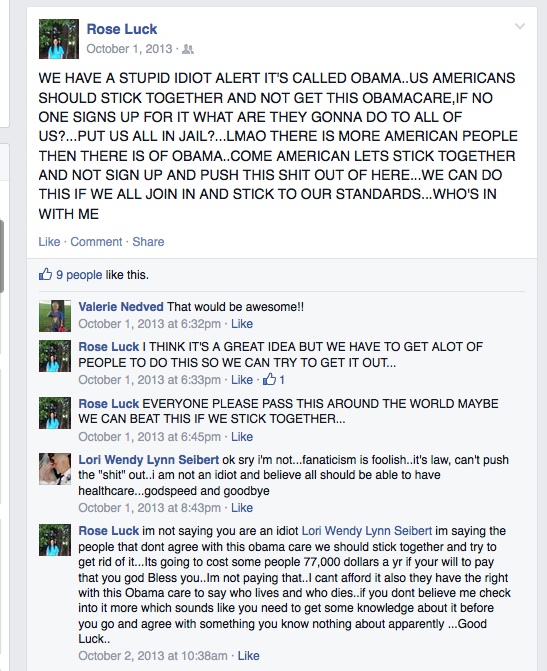

At 56, Luck is the youngest of the plaintiffs. Like King, she doesn’t care much for Obama. On her Facebook page, she has called him the “anti-Christ,” voiced her belief that Obama came to power because “he got his Muslim people to vote for him,” and noted her refusal to acknowledge his legitimacy as president. “Ohhhhh hell no i wouldn’t admit he was our president,” she wrote in one Facebook comment. She has warned her Facebook followers that Obamacare will cost people “77,000 dollars a year.”

Along with her anti-Obama sentiments, Luck’s Facebook page makes clear that she has experienced some serious health problems—she’s reported several trips to the hospital—and suggests she badly needs health coverage. Obamacare offers her a good deal in that department. Luck’s estimated household income for 2014 was $45,000. According to government filings, the cheapest plan available to her on the exchange cost $332 per month—not cheap because she’s a smoker, but also a better deal than the $428 catastrophic coverage available to her (at the time the lawsuit was filed) without the subsidy. Even so, the Affordable Care Act does not force her to buy a plan or pay a fine, for the same reason that King is exempt—the cost of subsidized insurance is more than 8 percent of her income.

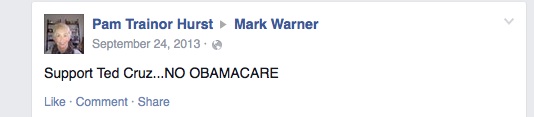

Doug Hurst

Hurst, 63, and his wife, Pam Trainor Hurst, owned a Virginia Beach remodeling company that went bankrupt at the peak of the financial crisis. According to their 2010 bankruptcy filings, which included their 2009 tax return, health care costs were a considerable expense for the Hursts. Their 2009 tax return lists more than $8,500 in out-of-pocket medical expenses.

Of the four plaintiffs, Doug Hurst is eligible for the most savings under Obamacare. According to legal filings, his projected income for 2014 was $39,000. Under Obamacare, he could have purchased a bronze health plan for $62.49 a month, a fraction of the $655 a month the bankruptcy filings show he paid in late 2010.

The Hursts no doubt understand the vagaries of the health care system—and the importance of insurance coverage. In 2009, not long before they filed for bankruptcy, Pam’s 37-year-old daughter was hospitalized and died, following a long struggle with schizoaffective disorder. The ACA requires insurers to cease discriminating against mentally ill consumers and to cover mental health treatment as they would any physical ailment, without limits, higher co-pays, or deductibles. I wondered how the Hursts felt about the fact that other families with loved ones contending with mental illness could lose access to health care if the King lawsuit succeeds.

I never spoke with Doug Hurst, but I reached his wife on the phone in late January. Her social-media footprint offers a glimpse into her politics, with Facebook posts displaying a fondness for tea party favorite Sen. Ted Cruz (R-Texas). She declined to talk about the case or the couple’s health care expenses, referring me to the lawyers handling the case. But she told me angrily: “I’m very well aware of my situation. You are not. You are not aware of extenuating circumstances. I don’t have to justify my life, the loss of my child, which included the loss of a business, to anyone, do you understand?”

The King case has had a strange trip to the Supreme Court. The four plaintiffs lost at both the district and the federal appellate courts. But the lawsuit remained alive thanks to a similar case, also spearheaded by CEI, that was heard by a three-judge panel of the DC Circuit Court of Appeals and had a different outcome—one that the full appeals court was expected to reverse after hearing the case. A reversal in the DC court would have meant there was no conflict among the circuit courts over the legal issue at the heart of these cases—and less reason for the Supreme Court to take the case. But the Supreme Court made the unusual move of accepting the King case before the DC Circuit could finish its work.

The oral arguments before the 4th Circuit Court of Appeals highlighted many of the weaknesses of King, particularly with regard to the plaintiffs. Judge Andre Davis repeatedly expressed skepticism about the plaintiffs and quizzed the lead lawyer on the case, Michael Carvin, on why he hadn’t brought the suit as a class action—the traditional vehicle for public interest litigation. Davis suggested that the reason was that “nobody wants what you’re after here!” The appellate court ruled unanimously against the plaintiffs, with Davis writing in a concurring opinion that Carvin’s case turned on “a tortured, nonsensical construction of a federal statute whose manifest purpose…could not be more clear.”

Carvin, an attorney at the law firm of Jones Day, bristled when I asked him whether the difficulty in securing solid plaintiffs suggested that there are not many Americans interested in wiping out health coverage for millions of their fellow citizens. “Linda Brown was the only plaintiff in Brown v. Board of Education,” he retorted, invoking the famous Supreme Court case that led to school desegregation. “Does that suggest there weren’t a lot of people who supported her point of view?”

Carvin told me that he’d had little interaction with the King plaintiffs and that CEI had been in charge of their recruitment. “My particular role was not a lot of direct involvement with the plaintiffs,” he said. (CEI’s general counsel, Sam Kazman, whom King and Levy consider their attorney, did not respond to repeated requests for comment.)

By the government’s math, which he disputes, Carvin acknowledged that two of the plaintiffs (Luck and King) don’t have much of a case because they would not be penalized for forgoing health coverage. But he says that doesn’t matter. All he needs is a single plaintiff who fits the bill to bring down the subsidy scheme, and both Hurst and Levy, he insists, qualify.

Though two lower courts have ruled against him, Carvin is confident that the Supreme Court’s conservative justices will tip the balance in his favor. If his case does result in wiping out health coverage for millions of Obamacare recipients, he said, it won’t be his fault. Nor will Luck, King, Levy, or Hurst be to blame. “If there is any complaint,” he claims, “it would be with the people who wrote the Affordable Care Act, not with my plaintiffs.”

*The story has been updated to reflect that Brown v. Board of Education was in fact a class action involving numerous plaintiffs, contrary to lawyer Michael Carvin’s statement.