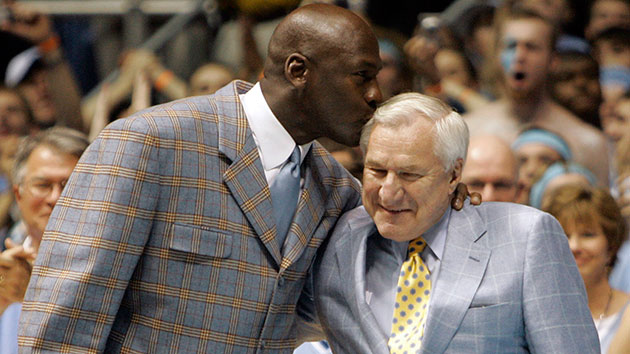

Michael Jordan with his college coach, Dean SmithGerry Broome/AP

Famed college basketball coach Dean Smith died Saturday night at the age of 83, after years of decline. His on-court prowess as the frontman at North Carolina from 1961 to 1997 is unforgettable: 879 wins, two national championships, 11 Final Four appearances, and a lasting legacy as a hoops innovator. But for many, it’s his off-court example—which manifested itself in something people in Chapel Hill still call the Carolina Way—that made him a legend.

Smith was an outspoken liberal Democrat who was anti-nukes, anti-death-penalty, and pro-gay-rights in a state that sent Jesse Helms to the Senate for five terms. (In fact, North Carolina Dems even tried to convince Smith to run against Helms.) His father, Alfred, integrated his high school basketball team in 1930s Kansas; years later, Smith would do the same at UNC, recruiting Charlie Scott in the mid-1960s to become the first African American player on scholarship there and one of the first in the entire South.

This story, from a 2014 piece by the Washington Post‘s John Feinstein, has been making the rounds today. It’s worth re-reading:

…In 1981, Smith very grudgingly agreed to cooperate with me on a profile for this newspaper. He kept insisting I should write about his players, but I said I had written about them. I wanted to write about him. He finally agreed.

One of the people I interviewed for the story was Rev. Robert Seymour, who had been Smith’s pastor at the Binkley Baptist Church since 1958, when he first arrived in Chapel Hill. Seymour told me a story about how upset Smith was to learn that Chapel Hill’s restaurants were still segregated. He and Seymour came up with an idea: Smith would walk into a restaurant with a black member of the church.

“You have to remember,” Reverend Seymour said. “Back then, he wasn’t Dean Smith. He was an assistant coach. Nothing more.”

Smith agreed and went to a restaurant where management knew him. He and his companion sat down and were served. That was the beginning of desegregation in Chapel Hill.

When I circled back to Smith and asked him to tell me more about that night, he shot me an angry look. “Who told you about that?” he asked.

“Reverend Seymour,” I said.

“I wish he hadn’t done that.”

“Why? You should be proud of doing something like that.”

He leaned forward in his chair and in a very quiet voice said something I’ve never forgotten: “You should never be proud of doing what’s right. You should just do what’s right.”

RIP, Dean.