Richard Drew/AP

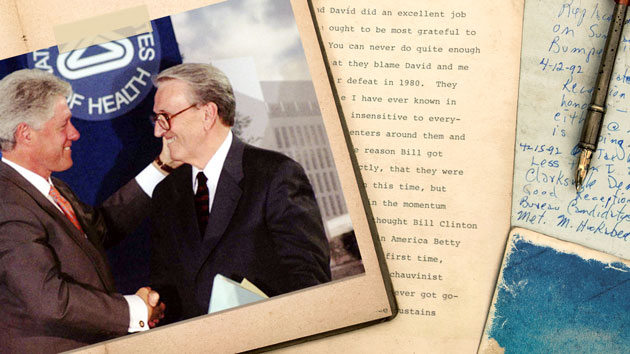

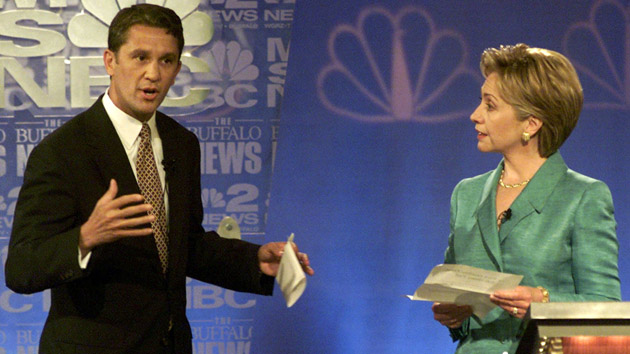

On the evening of September 13, 2000, after his first debate with Hillary Clinton, Rick Lazio was feeling confident. Several polls had shown the Republican congressman ahead of the first lady in the race for New York’s open Senate seat, and Lazio and his team felt the debate had bolstered his lead. He wasn’t alone in this view. “The post-debate conventional wisdom was clear,” Michael Tomasky wrote in Hillary’s Turn, his account of the contest. “Lazio had won.” Even Patti Solis Doyle, Clinton’s chief of staff for the Senate campaign who would go on to head her 2008 presidential bid, wasn’t confident her boss had come out on top. “I wasn’t actually sure how it was going to play,” she tells Mother Jones. But Lazio and his allies were not taking into account a moment during the debate that was not immediately or widely recognized as being a problem for him.

This key exchange came at the end of the debate, when Lazio interrupted Clinton mid-sentence, walked across the stage with a campaign finance pledge in hand, and urged her to sign it. Clinton awkwardly tried to shake Lazio’s hand as he towered over her, his finger wagging in her face. In the hours and days after the debate, Clinton’s team worked mightily to turn this interaction to her advantage. Clinton aide Ann Lewis told the press that Lazio had “spent much of the time being personally insulting.” Howard Wolfson, another veteran Clinton hand, said Lazio was “menacing” to Clinton.

“They saw this opportunity and they drove it and that’s the clip that was on TV over and over again,” Lazio says now. The next day, media outlets began to embrace Wolfson’s portrayal of Lazio as a sexist bully. “In Your Face,” proclaimed a headline in the Daily News. Jon Stewart titled his segment on the debate “Rodham ‘N Creep.” Eventually, the Clinton campaign’s depiction became the dominant assessment. Lazio was “Darth Vader with dimples,” Gail Collins wrote in the New York Times later that week. Clinton went on to win by 12 points.

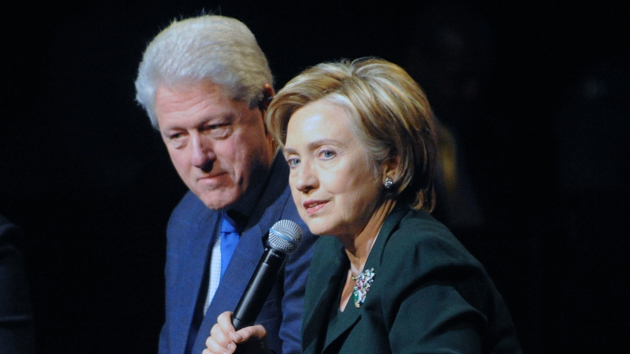

Clinton is now preparing for a second presidential campaign, which multiple outlets have reported she will announce early next month. Though some societal attitudes have no doubt shifted in the past decade and a half, the Republican presidential nominee—who will likely be a man—would do well to pay attention to how charges of sexism shaped Clinton’s first race. At least, Lazio believes that. He notes that Republicans who aspire to beat Clinton should realize that if the Clinton campaign “can connect with women who have faced sexism…it will resonate. This is going to be one of the tactics to put the Republican on defense.”

Charges of sexism—from the press, campaign surrogates, or even candidates themselves—are a fixture of modern American politics. In 2014, then-Sen. Kay Hagan’s campaign criticized her opponent, Thom Tillis, for calling her “Kay” instead of “Senator Hagan” during a debate. (Tillis ended up winning in a close contest.) In 2012, staffers for Elizabeth Warren accused then-Sen. Scott Brown of being condescending by repeatedly calling her “Professor.” That year, two Republican Senate candidates, Todd Akin and Richard Mourdock, lost crucial Senate races after making bizarre remarks about rape. (Some Democrats will accuse Republican men of sexism “regardless” of their actions, Lazio contends, “but there can be self-inflicted wounds.” He warns that “words or actions that would be considered by a fair-minded person to be egregiously sexist” will get any candidate in trouble.) In 1990, Ann Richards won a race for governor of Texas after her opponent made a rape joke and later refused to shake her hand in public.

Lazio’s debate maneuver is “the example we use all the time” of a male candidate’s blunder that helped his female opponent, says Kelly Dittmar, an assistant professor of political science at Rutgers University who studies gender in politics. Democrats, of course, have also been accused of sexism in campaigns. Clinton surrogates charged that Barack Obama was condescending to her during a debate in 2008. But the charges seem to stick to Republicans more often “because they fit the narrative that we have,” says Kathleen Dolan, a political scientist at University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee who also focuses on these issues.

Lazio agrees. “I do think the media, broadly speaking—this is a gross generalization—tends to be sympathetic to these charges, particularly when they’re levied against Republicans,” he says. This is partially because “it fits into a narrative that many of them have that Republicans are insensitive to women,” he argues. He cites the example of former Rep. Pete Stark, a Democrat from California who in 1994 claimed that then-Rep. Nancy Johnson, a Republican who was married to a doctor, learned everything she knew about health “through pillow talk.” Stark apologized, but went on to serve another two decades in Congress.

Dittmar has surveyed scores of political professionals about gender and politics, and most of them agree that running against women carries certain risks for male candidates. “In my surveys, two-thirds of the respondents said, ‘Yeah, men do need to tread carefully'” when running against women, Ditmmar says. She adds that male candidates tend to be more worried than campaign managers and consultants about the possible pitfalls of competing against a woman—and Democrats are generally more worried about this than Republicans.

That caution can affect campaign strategy—fewer negative ads on personal issues, for example. How a male candidate handles personal interactions, such as debates, with a female opponent is particularly important, Dolan argues. Those in-person interactions—”those things in the moment,” she says—can define a race and stir voters’ emotions.

Mary Beth Rogers knows this well. In 1990, she ran Ann Richards’ campaign for governor of Texas. Richards’ opponent, a millionaire rancher named Clayton Williams, put his foot in his mouth early in the campaign by making a joke about how rape victims should just “relax and enjoy it.” But it was a physical interaction, not the rape comment, that most damaged Williams, Rogers says. That summer, Richards and Williams appeared together before a meeting of the Texas Crime Commission. “And Ann came up there on the stage, and she stuck out her hand and said, ‘Well hello, Claytie!'” Rogers remembers. Williams refused to shake Richards’ hand. “Fortunately for us, because this was one of their first appearances together, it was on television and it was played every newscast in the state,” Rogers says. “Twenty-five years ago in Texas that was a very ungentlemanly like thing to do. We felt that that was a key turning point in the campaign.”

Four years later, Richards ran for reelection. Her opponent that year was George W. Bush, a failed congressional candidate then serving as the managing general partner of the Texas Rangers baseball team. But Bush had learned from Williams’ mistakes. “He was the perfect gentleman throughout the whole process,” Rogers says. “A model of propriety, respectfulness, and kindness to Ann. That perception of Republicans as more insensitive to women certainly did not come through in the Bush election.” Richards lost, and Bush went on to serve a term and a half as governor before becoming president in 2001.

Another Republican candidate who proceeded carefully when running against a woman was New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie, a Republican with a reputation as a bully. In 2013, when he faced challenger Barbara Buono, a Democratic state senator, Christie “did a pretty good job” reining in his baser instincts, Dittmar says. “I’ve heard members of his team talk about this,” she notes. “Regardless of the fact that he was in such a huge lead, perceptions of him as a bully already led him to be particularly cautious in those debates going against a woman candidate. So his campaign folks have mentioned that the goal in that was to keep it very steady and not react in the way that would yield those outcomes.”

Most campaign consultants now train candidates to avoid Lazio-like missteps, Dittmar says. “Don’t invade her personal space” is a prime directive. But the men who want to take on Clinton will need to be careful to steer clear of sexist tropes that will repel female voters and could rebound to boost Hillary, Solis Doyle maintains. “Whether it was during the Lewinsky scandal or whether it was when Lazio was bullying her, people seem to like damsel-in-distress sort of thing,” Solis Doyle says. “Which is sad to me, but it helped her [as first lady] in ’98 and it helped her in 2000 certainly.” But it didn’t win her the race in 2008, when she was perceived as the clear front-runner. “When she has been quote-unquote ‘victimized,'” Solis Doyle says, “she’s been more beloved.”